On two Sundays in late summer and early fall, we interviewed Alfie Pollitt at the North Philadelphia home of Anthony Monteiro. We found Alfie to be not only generous, but warm and kind, qualities often associated with great artists. We spent close to six hours exploring the many layers of Black music and how it is manifested through the Philadelphia Sound.

The Saturday Free School had previously interviewed Alfie; however, we felt that this moment in history demanded we return to him. We embarked upon this interview with our own philosophical and ideological assumptions. First, this is the Year of James Arthur Baldwin’s centenary. Baldwin’s ideas of art as an act of love and revolution in the Black struggle informed his view that going forward, America must become the “last white nation.” Second, more than anything, we are informed by a fierce urgency of now, to prevent world war and to end the genocide against the Palestinian women and children. Thirdly, we believe that Alfie lives a principled life: he is therefore an exemplar for artists.

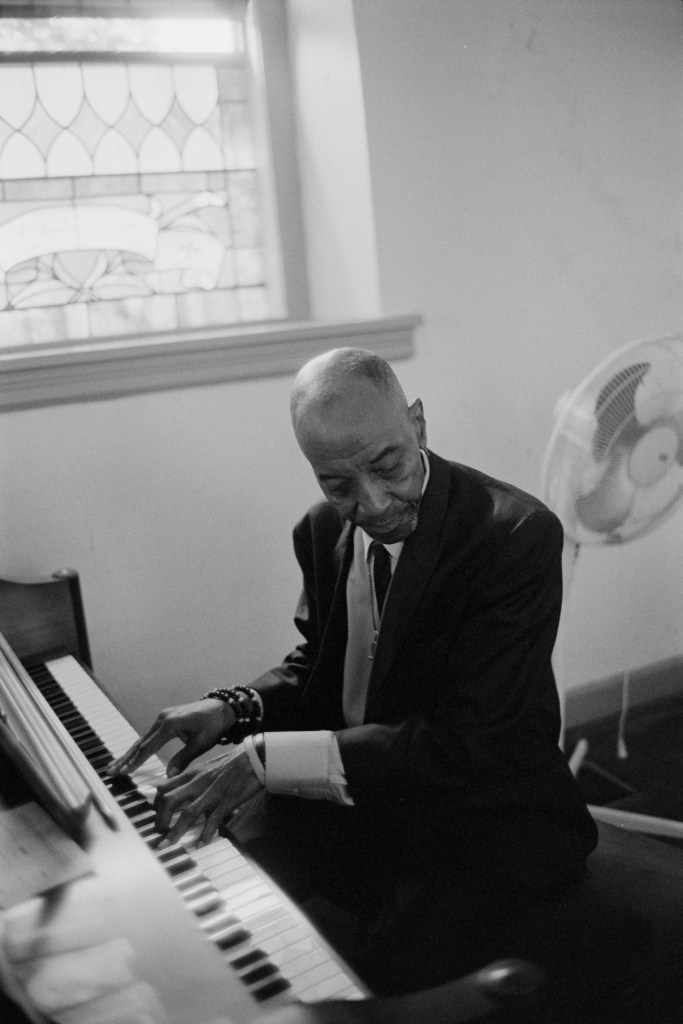

He plays in churches, at banquets and celebrations, public parks and community events: continuously becoming more intertwined with the lives of the people of Philadelphia. He shares in their daily joys and suffering, so that he may know them better and heighten the quality of the lives they lead. His music is clear and resonant, through which one meets the truth of what James Baldwin writes, “Where the poet can sing, the people can live.”

Alfie developed within what is in effect a Black civilizational tradition. This tradition has allowed the American people the possibility of relinquishing whiteness. In essence, this tradition grounds what we would like to call the Black Proletarian Imaginary: a futuristic consciousness.

Alfie was born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania in 1943. His life was intertwined with the genesis and maturing of the Black freedom movement and the great musical revolution that emerged from it. This was a period of struggle and upheaval in the country. The Civil Rights Movement, America’s Third Revolution, transformed the nation. Philadelphia, and North Philadelphia in particular, produced a post-WWII generation of talented singers, dancers, and musicians: Doo Wop, Bebop, Hard Bop, Free Jazz, and Rhythm & Blues were a cradle nurturing new sounds. This aesthetic matured from the late 1940s into the 1970s; ultimately becoming known as The Sound of Philadelphia.

The Philly Sound defines love as a concrete task and responsibility, a moral choice that struggles against the white supremacist social system and furnishes spiritual sustenance for a struggling people. Opposing the governing elite’s agenda of war, poverty and racism, the singers, arrangers, lyricists, and performers exuded an unmistakable moral uprightness and grounding in the Black masses from which they emerged. Love, peace and humanity are its guiding principles.

Today, in the Black music tradition, Jazz is assumed to be more advanced than Rhythm & Blues because it is more abstract and favored by sophisticated audiences. Moreover, the most modern expressions of Jazz are assumed to be avant-garde because they seem more complex and produce less familiar sounds. However modernism should not be conflated with abstraction. Each genre in the post-WWII era is part of a single garment of musical creativity. Each manifests the people, The Black Proletariat, from which it comes.

No people answered the cry for modern thought more fully than African Americans. As a social group they possess the most complete understanding of what W.E.B. Du Bois called “the problem of the twentieth century,” the color line. This constant struggle of Black folk against white supremacy, capitalism, and for the unfulfilled goal of freedom, produced a rich spiritual and social tapestry from which original, highly conscious, and distinctly modern music sprang.

Alfie possesses an intimate understanding of the Black Proletariat, and his music acknowledges their interior lives and the deep suffering that generations of his people have endured in this country. Colored People’s Modernity, struggling to be born from the ruins of white modernity, in many respects is the task the Sound of Philadelphia seeks to achieve. A task of world historic and revolutionary significance which can only be achieved to the degree that the artist, and in particular the musician, links themselves to the aspirations of the oppressed.

Interview by Michelle Lyu, Kathie Jiang, Anthony Monteiro.

Alfie Pollitt

WORDS ON WORDS

I want to raise this question of how to sustain, you know. Because I think people today, a lot of them have this belief that you have to compromise. You compromise here and there, it’s okay, this thing is transactional, it’s okay if I sell out a little bit. And I think what the argument we’re trying to make is that well the artist cannot compromise. And the artist must take a side. And the only contribution a true artist can make is for freedom and that means something concrete.

I’m just fortunate to be able to do what little I be doing, you know, and to be able to do that.

Man I found out stuff, I seen this interview with Eric Dolphy’s mother and father a few days ago you know. And they wasn’t like—you know, some parents—“I don’t know with my son, he went off. What is he doing, what is that?” They was like, understanding, and the interview person asked, “Well did he ever, how did he succeed or make it?” He said, “Well he ain’t really make it.”

(Laughs) His father said that?

Yeah, “He ain’t really make it.” I mean, he didn’t really make no money doing this, you know what I mean. He went to New York, people didn’t want to play with him. In the Western classical music community he was sought after—flute stuff, and bass clarinet, and stuff like that you know.

I saw him one time, it was a big thing. Whatchamacallit. It was on national TV. It was Oliver Nelson who was conducting it, and it was Hank Jones, Elvin’s brother on piano. Art Davis on bass. And Eric was on flute and bass clarinet. It was a big, you know, big, big thing. Hollywood, you know, big money into it. It was top class. But they were sought out because of what they could do. Respected that way, but you know, maybe situations like that may be far and few between. To get a gig like that. As opposed to playing for the door—money comes in the door at a club or coffee house or something, you know.

I guess, the drive. The drive. I’m driven to want to play.

I feel like a fish out of water if I don’t sit down at the keyboard and play at least something—try to, you know, each day.

Some people, man, they just think magically, they just want to just play, you know what I mean. Play masterfully. Because they listened to somebody else and then they play it and then their friends tell them, “Oh, you’re sensational!” And miss some steps in between, as far as their growth and development, what it takes.

Where do you like to play these days? What are the gigs?

Whoever would hire me. (Laughs) Not whoever.

No, but you’re selective.

Ideally, where people appreciate the music and will listen to it and you know, grow from it. Whether it be straight ahead, or R&B. I don’t gravitate towards you know like, night clubs. Unless, you know, somebody out there got a night club and appreciates the music and presents the music as it is: art. And so people come in with the mindset that they’re going to receive art you know, which is reciprocal, give and take, from the listener and the performer. I would say.

Your knowledge, your experience. For people that don’t know; but she said like, here’s Alfie. He done play with Russell, he done play with Teddy, he done play with this, the other, then he know the whole Jazz thing here.

Well I just feel that this whole tradition is being cheapened. Your tradition. It’s why I’m thinking about this interview so much, and how important it is and how important your life is. Yeah I mean you already know how I feel about what you’ve given, but you know I’ve watched it be degraded, and I do feel some type of way about it. And I think the record is going to have to be set straight. And I think there’s a battle. I think there’s a fierce battle about what this music is and who it belongs to. And we’re trying to make that clear, that it doesn’t belong with the white world, you know. It’s been made by men like you.

As per like ownership. Ownership. Possession. Ownership.

Well, you call it healing music, that world calls it entertainment, you know.

Yeah, like entertainment—I do R&B, that’s like entertainment, we do that. That’s more like entertainment to me. You know, ‘cause people come for entertainment, to reminisce about romance and times they had back in the day and you know, that kind of thing. Not as a negative. But I mean it’s more so, when we play—you come out to Ardmore, you see that? People come out to get fed. And like you said about the quantum physics piece, remember you said that a long time ago? And I thought about it, I said, I take myself away from that—that ain’t me. I participate. I’m grateful to be part of stuff come through me, that touches people.

I feel like this music is for all people, including white people. I feel like that’s part of what you’re saying.

Oh, of course.

But not in that way you know, not on those terms.

Because if you look at the whole planet, everybody is a so-called African. Everybody on the planet. Everybody.

PHILADELPHIA FREE JAZZ / AVANT-GARDE

Could I ask you about Giuseppi Logan and Khan Jamal? First Giuseppi Logan, because you mentioned avant-garde.

I could talk about both of them.

And who was the reed player, who was with Khan Jamal…

Byard?

Byard. Yeah, him too.

Okay. Well, Giuseppi. I met Giuseppi before I met Byard, Khan and all of them. I met him through hanging out with Nate Murray, down Lancaster Ave, I think it was at a place called the Bar Nun on Wyalusing Avenue and 56th. And they used to have a jam session. And this sax player named Jimmy Savage, was an alto player, he was really good; and he would host the session. And it would be a cutting session, you know, people would try to out play other people. So he was like the star alto player and that was his kingdom, that bar, right. So, Giuseppi came in town from Norfolk.

I thought he was from Philly.1

No. Norfolk. He came here, he had a big family, had his family with him. I think he got busted for possession or something. So he had to stay here for a minute.

And he came to this session, and he sat in. And you know, Jimmy, the guy, leader of the clan, you know—“Man, what’s going on”—Giuseppi blew him off the stage. So, I mean. ‘Cause Giuseppi played about nine different horns. Yeah. So Giuseppi heard me play—he liked my playing. So he said, while he’s in town, he had to wait to go to court, and he had some free time during the day.

And I was living at home in Bryn Mawr then, with my parents, my brother and sister. So he would come on out to Bryn Mawr and we went to my godmother’s. And my godmother was my piano teacher. She lived around the corner from us. And you know, with her, I studied a little Mozart, you know, stuff like that. We’re playing teas, recitals and stuff. And you know, it was like we got put on the spot—“Little Alfred is gonna play for us.”

But she was a real wide open person. Because I studied with her, and I was learning all these different pieces, you know out of them books. So she noticed that I was becoming a teenager. I was a teenager and my interests were, you know, I had other interests. She said, “Well, bring in something that you wanna, you know, that you’ve been listening to and we’ll see what we can do.” So I brought her in this book, it’s a book that had a picture of Thelonius Monk and a little red wagon sitting on the album cover. So we tried to figure out Brilliant Corners, and “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are,” a song from the Brilliant Corners album.

And she never like, judged me or said, “Oh no, no, we don’t do that here.” So, I took a chance when I met Giuseppi, you know, because my godmother had a nice piano. A baby grand piano. And you know, during the day, she was home weekdays, so I asked her if Giuseppi, this guy I met, could come over and practice. She said yeah. So we was over there, so we was playing out. So to speak. And she never put us out of the house, or called the police on us, none of that—reprimanded us. She, you know, let us do our thing, you know, like the next day we’d come back.

But Giuseppi told me that he liked Eric Dolphy. Because he said Eric is worse than Coltrane. That was his words.

Better than Coltrane.

He say worse.

Worse.

Yeah, I guess more out. He liked Trane, but liked Eric more so.

Wow.

Okay so, that was in the early to mid ‘60s. I met Byard—

Could I just ask you one more question about Giuseppi? Giuseppi went cold blooded avant-garde.

Pretty much, yeah.

Then he disappeared suddenly. Went over to New York and disappeared. What happened to him?

Well 1966, I was working in Montreal at a so-called jazz club up there. And then I came home and while I was home, I went to New York to hang out with Giuseppi. He was living on the Lower East Side, and he knew Rashied Ali. Remember I told you the bridge we walked over, Manhattan Bridge? We walked across that bridge over to Rashied’s studio he had at that time. And we did a jam session one afternoon and Rashied recorded it, and I don’t know where that, if it exists or anything.

But Giuseppi, he was signed to ESP label, you know. And I guess he was a threat some kind of way, and so to kind of take him down, people found out his weakness.

What was his weakness?

His weakness was these women.

Women.

Caucasian women. And they got close to him—according to what I heard, and put something in his food and just diminished his wind power as far as the playing sax and everything. And then eventually I don’t know what happened ‘cause I didn’t keep in touch with him. I was looking on YouTube and I saw this thing about “rediscovered Giuseppi Logan” in the Village, St. Christopher’s Square or something like that. And this guy that rediscovered him—wait a minute, did I see you at the concert?

Here. Yeah, here, when he was down in Philly.

No. At the Art Alliance. My brother was doing that. ‘Cause we were down there, ‘cause he knew my brother too.

But Giuseppi was homeless over in New York for years, right?

According to what they say. He didn’t have a horn or nothing.

These white young guys, they found him. They brought him back over here, but he would start playing and then he’d lose himself, or they had to have somebody with him.

When he was at that show, he could only play but for so long—endurance; and then he would run out of gas.

I thought it was a mental thing.

No no, he didn’t have the wind power. Didn’t have the qi, didn’t have the life force, the breath, to be able to. According to my observations. And my brother, he felt the same way.

‘Cause my brother used to live in New York. He went to art school up at Art Students League in Manhattan. He was up there with, I’m talking about Stanley Whitney, painter. Another painter, James Phillips. They’re all from Bryn Mawr; they were all contemporaries with my brother. And they were under my mother. My mother was an artist, a painter. And my best friend Jervis Holley, he was like my age but he was a great painter, so he mentored them and my mother mentored Phillips, Stanley Whitney, and my brother Harry Pollitt. And I introduced Phillips to Rittenhouse Square.

Oh, boy (laughs).

The street. The way, how to survive on the street, off the fat of the land so to speak. (Laughs) And you know, introduced me to so-called jazz. So, I mean if you check out some of these interviews with Stanley Whitney, he says he don’t paint unless he got music playing. Phillips—the same way. So anyway, Phillips and Stanley, my brother, and I, we crashed where we could, in that early life as young bohemians so to speak.

So they knew Pharoah Sanders and Rashied Ali and different people. Elvin. They seen Trane. They was younger than me, but they were part of the wave of some of the people who were around to see Trane and them. So a lot of people nowadays man, never seen Trane. And that was like, it was like, you know. He would give sermons. It was, like Alan Nelson and myself, we were part of the Coltrane, McCoy, Elvin—disciples.

We were going places; we was underage and we’d go to Pep’s and Showboat. And the guys like Freddie Freeloader—Miles named a song after him, Kind of Blue album—was a bartender. And he would let us come in and drink fruit punch and sodas and see our heroes, you know. So we were blessed to be able to sit at the feet of these folk.

I saw Sun Ra one time. First time I seen him, he came in Pep’s as a side man.

With who?

Walt Dickerson, vibraphone player. It was him. I think, might have been Marshall Allen, and I think Ike Quebec or somebody. Pat Patrick. They were sidemen for Walt on this gig, you know. But yeah, this music was an influence. Was a great influence on my life, you know what I mean.

You remember the brother who used to play vibes from down South Philly?

Bill Lewis.

Bill Lewis. Very avant-garde, very futuristic—

Futuristic thinking cat. Yeah, Bill gave me a band one time. Gave me a tenor player, trumpet player, bass player, and a drummer. But I couldn’t hold it together ‘cause I was out there, during that time. Up at Lee Cultural Center, 44th and Haverford, gave me a band.

So what about Khan Jamal and them?

So, I met Byard in ’66 at a jam session up at Pleasant Playground, at Boyer and Pleasant, up in Mount Airy section called Dogtown. They all lived around that way, and Byard was like—

That’s where Archie Shepp is from.

No no, Shepp is from the Brickyard.

Brickyard, I’m sorry. Forgive me.

Brickyard, Wister Street and all around there.

So Byard, you know. At that time, Byard was home from school, Berklee College of Music. He’s one of the first cats from Philly who went up there, you know, way back. So he was out, and I just loved his sound. Had the Trane stuff, and Eric, and different things. So through him I met his boys—Khan Jamal. I met Monnette Sudler, Bill Meek, piano player. The whole Germantown crew, you know. And I worked with Khan. I worked with Byard and Khan together.

And they was definitely out.

Yeah.

Bill Lewis.

On purpose. Mhm.

On purpose, yeah. Oh yeah.

And the band we had with Byard was like, we had three drummers.

Wow.

Caucasian guy named Bobby Kapp. Guy a little older than us named J. R. Mitchell. And Eric Grávátt who was younger than us. Eric who worked with McCoy Tyner, Weather Report.

Really.

Mhm. Eric was one of the Byard’s mentees, you know.

So we had three drummers. Jerome Hunter on bass, Byard on sax.

Khan on vibes.

Khan on vibes. Monnette Sudler, guitar.

Woah. Shit.

And then other horn players would come and play with us; a guy named Liptus Saturn. He was a cat that came out of this school like when Trane, when Ascension, when that was released. It was horn players who were not really, didn’t study saxophone but they heard Trane, Archie Shepp and Ornette and them.

They heard the aspect of honking and screaming on the horns. So they went and got into that, and they went out and they even got paid for that; they’d never really studied the music. Whereas Ornette, Trane, and them were like—music systems. Studied all that kind of stuff.

The reason I ask about them, Giuseppi and Khan and all of them. It’s almost like they’re forgotten figures in the Philadelphia avant-garde.

Mhm.

Bill Lewis. And these are very, very—

‘Cause Bill Lewis started the Long March—

That’s right.

—Jazz Society, whatever it was called. In fact I was on a committee with, it was Bill Lewis. Ron Everett, trumpet player, sang with the Castells singing group and he was also a trumpet player, jazz, wrote songs, wrote plays. And Byard, and, what’s my man’s name—Gino, from Gino’s Empty Foxhole. Gino Barnhart, who I met through Byard. His church had that space where the Empty Foxhole took place, you know, let them use that space. But yeah, we was on the Long March committee together, you know, the advisory committee or whatever. Bill Lewis, Byard, Ron Everett.

I wanted to ask you to say a bit more about Giuseppi Logan’s contribution to this music.

He was mistreated by the system. He was a great talent. And I think some of that was envy and jealousy, people that took him down. In New York, in the Village, the East Village.

And then when he came back and then we went in to see him perform, he hardly had any breath power, wind power. And it seemed like the guy that was the leader of the band that was kind of looking out for him, was kind of like. It seemed like, was kind of pimping him, you know what I mean. Like Barnum—“Here’s my side show, here’s my Elephant Man,” or whatever. Okay, after the show was over—“Put him back in his cage.”

But Giuseppi, did he play with Albert Ayler and them?

Well, not Albert Ayler. They had different—Marion Brown, Albert Ayler, John Tchicai, Prince Lasha. All these different people had their own expression. He was part of that wave, you know; that group of folk, that expression.

Even there was a guy, remember this guy—what was his name? He was a so-called avant-garde alto player. Joe Harriott from England. He was part of it, but he was in England doing similar type music, back in the ‘60s.

So Giuseppi was in that East Village group.

Yeah.

Marion Brown.

Sun Ra. Sun Ra, they was all living down there. Pharaoh, Rashied Ali, Dewey Redman. Bunch of people. A guy named Marzette [Watts], have you heard of Marzette?

Marzette was a tenor player, he was part of the Village Loft scene. And he would—my friend James Philipps, the painter, him and Stanley Whitney and them, they was in the Village during this time back in the ‘60s, right, so they were around seeing these different people, different characters. So like Marzette was a guy, he would wear a cook’s uniform, like a cook’s hat, and play. Just like—what’s the guy’s name? The guy that played with the—

Used to be with the Art Ensemble.

Art Ensemble.

The trumpeter.

With the lab coat on.

Yeah, like the surgical thing. Doctor shit.

Not unlike Flava Flav with the clock. Identify with your own brand, part of they brand.

You would call him avant-garde?

I guess that’s the term people use, but you know, “so-called.” I say so-called, about all that stuff.

I wanted to ask you about Odean Pope.

Well he’s a good friend of John Coltrane. And you know, they played together, practiced together from what I understand. From when Trane was living here.

Odean practiced with Coltrane?

From what I understand, yeah. He used to be at the Coltrane House, when Trane was living there, from what I understand. Him. John Glenn, he was a tenor player, one of Trane’s contemporaries. And he from Philly. But he had kind of like a Southern accent, maybe he was not originally from Philly, but I knew him from Philly, West Philly.

But he supposedly influenced Trane to do multiphonics, playing more than one note at the same time.

Who was this, now?

John Glenn. And I was blessed to play with John. I played with, you know, a lot of people in the scene here back in the ‘60s. John was one of them. He was a great tenor player, and he sounds similar to Trane.

PHILADELPHIA RHYTHM & BLUES

I want to follow up on something from the first interview. And it was when you talked about your discovery of R&B because my understanding from the first interview was that at first there was a certain hesitation you felt toward the music, because you said that it might be like sellout music.

Oh, let’s go back before that though. There was a guy that lived in my neighborhood, he lived in Haverford. He played the piano by ear, and he stomped on the floor. And he amazed me, you know what I mean, I wanted to be able to do that. He couldn’t read music. And we were playing like Fats Domino and Little Richard, that kind of music, you know what I mean. And then sometime after that I was singing doo wop. So I was doing—you know, things shifted, you know what I mean.

Later on, in the so-called staunch jazz—“I ain’t going to do the other kind of music” type thing, vibe, and then things shifted. Because as I was saying, because Billy Paul and Norman Connors and us, we was like, “We ain’t selling out, we ain’t playing that.” Then I started hearing them with hit records you know, and said there got to be something to that, because if they buy into it, there’s got to be—let me investigate. And I’m glad I did.

And then I saw, those are great people. You look at Bobby Martin, the arranger. You look at Thom Bell, the arranger. These people, the stuff they did, like world-class. I mean, you know, like Beethoven and all them guys, you know what I mean, type level and beyond. Put their own spin, their own unique originality with it.

And then people be telling me I got my own sound, so I try to work on that, I just accept that and try to be myself. When I grow up, I’m gonna get some long pants though (laughs).

(Laughs) Yeah. So would you say you followed their lead to an extent, Norman Connors and Billy Paul, into R&B?

Yeah. Mhm.

Not directly, because they were living in Hollywood and other places, and New York. And I’m in Philly. And I’m in the Nation [of Islam]. On the day to day I’m selling Muhammad Speaks, fish, all that kind of stuff. Trying to be married at the same time. And trying to not get all my bills turned off, you know. (Laughs) You know. And people saying, “Why are you with that Muhammad guy?”

(Laughs)

You know (laughs). All kind of stuff.

And then years later, when I grew locs; before that, my brother and I, we were some of the first guys who had afros on the Main Line, of our generation. And these women would say, “Boy, you better not fall asleep, I’mma cut that hair off. Don’t fall asleep around me, you need to cut that mess off your head boy.”

(Laughs)

Right? You probably experienced something similar.

I don’t know about that, ‘cause I’m from the hood, man. You from the suburbs.

Well, the hood? Ohh, oh, man. You gotta throw that in there. See.

(Laughs)

Come on, man. Come on, Tony. Come on, man. Can’t you relate? Can’t you relate!

(Laughing) No, I can’t!

Alright, it’s okay. ‘Scuse me, you got the floor, go ahead.

(Laughs)

Wait a minute, tacit, tacit, tacit. You got the floor, go ahead. Take it away. (Laughs)

Well I’m trying to understand, or just hear a little bit more about—

I followed them from a distance. Not directly, went to him—“Why are you playing” or, you know. Yeah, but I studied, you know, some of the music and tried to emulate on my own without any, really, somebody directing me. Just using my ear and trying to, you know, that kind of thing.

I’m trying to understand what the birth of this Philly R&B sound and movement looked like.

What it looked like?

Like how it began.

People playing in taprooms and bars and stuff. Cabarets. Like, from what I been told. Like Kenny Gamble and the Romeos, okay. The band Kenny and them had before Philly International stuff. They would play in cabarets.

Tell them what a cabaret is.

A cabaret is a party. People go to like, rent a dance hall, or skate rink or something, and have dance in there. And people bring their food and liquor and stuff, and they party. And at that time they would dance and party to the band that’s playing for the event. And the band, they knew Chico Booth, King James, Kenny Gamble and the Romeos; three examples of groups that they listened to. They had their pulse on what was on the radio and what’s moving people. So they learned that stuff. So people had a good time, without a DJ back then, you know what I mean.

So when Kenny and them started recording, him and Huff and them, they were going to the studio and they’d take some musicians in. And they might have an idea for a song, just like a line or something. And actually, the musicians really create the song. Because the musicians did what breaks Motown, breaks with what was popular then and stuff. And so it’s combination of stuff that then Gamble and Huff would record that and go back, write the song. And according to what I heard these guys never got compensated for—they really helped create, collaborated on these songs.

Could I just ask—so Kenny Gamble and the Romeos. Kenny Gamble had a group, and it was the Romeos.

Right.

And a cabaret is like, you see—Blue Horizon. You know what a Blue Horizon is. People would rent it and then you could come there, bring your own whiskey, your own beer.

Food.

Food, that’s right. And party.

Indoor party.

Indoor party. So Kenny Gamble and them was in that circuit, that cabaret circuit.

Yeah, cabarets like the Imperial Ballroom. On 60th Street. The Olympia Ballroom, what was that 52nd and Baltimore. Cosmopolitan.

So you saying that the musicians, you know would make the music. But then the songwriters, let’s say Kenny and them, would take credit for it.

Take credit. And financially benefit. Probably based on the model that they had, and what they had to go through. I mean for songwriters, you know. People like the Cameo Parkway label, you know, the big guys—“We’re giving you a break. We’re going to record your song.” And so maybe the artists think it’s a great chance that somebody is giving them.

We’re just coming off such a beautiful performance yesterday. And knowing that you also perform at the Ardmore retirement home. I’m curious, why do you play where you play? Or where do you not play, you know, that sort of thing. I think a lot of young people need to hear, or a lot of people need to hear—

Yes, so the tradition can be more intact. Win-win situation. Hopefully, and be able to maintain that.

Say a little bit more about why you do Jazz and R&B.

Well, the R&B. See, I was blessed to be around Philly International Records, Sigma Sound Studios, and be around producers and arrangers and songwriters and record promoters and radio people, DJ’s. And having worked with—the first gig I did in really dedicated R&B Philadelphia Sound stuff was in ‘74 with Major Harris.

So how that happened was, I had been active in the Nation of Islam, which I was at that time. And you know, basically selling papers, and I stopped playing music because I was doing 300 papers a week before I got my X. And I was blessed to maintain it from ‘69 to about ‘75, more or less.

So, abiding by what my understanding of some of what Elijah Muhammad’s teachings were about: music and sports and sporting players; it’s a carry over from the plantation system, where a slave owner would have his buck Negro guy fight against another one’s. And they’d fight to the death. And bet money on them, and you know—hey, somebody lose their life, no big deal, next. That kind of thing. So that’s what’s called “sport and play.”

And then like trickle down to this day and time, most of the money that Black people make is like as a musician, you know, the big money, and athletics. So it’s called “sport and play,” so it was frowned upon, even though Muhammad Ali, he was—I wouldn’t have had him stop fighting, if I were to have a kind of influence on the time.

So we were told that “sport and play,” it’s uncivilized. And it said that the civilized person would pat their foot to music inside their shoe where nobody could see him, you know what I mean. And like “no emotion” that kind of thing. But one of my lieutenants, who has, he made transition, Lieutenant Thomas 14X—he said, “Look, brother, you got a gift.” And plus he promoted me, as far as, you know, he’d tell people, “Yeah this brother Alfie here, you know, selling his papers, y’all need to be like him.” But he had a revelation, and said. He said, “You got a gift. Don’t get so spooky with all these rules and stuff, and do that music.”

And he started something called the “Night Out with the FOI” which was Brothers who were former—came into the Nation as musicians and what have you. Who became, you know, a minister or became a secretary—gave up music totally. Worked in the restaurant, or this and that, and just had a job selling papers, making money off of papers and products from the Nation. So Brothers came back to their instruments, so he started that, and that’s how I got back into it.

And then, also I started hearing Norman Connors and Billy Paul having records coming out that were crossing over. Because see, back in the day, Norman and Billy Paul and all of us, we lived together down at a studio, 1430 South Penn Square. Across, something across—real estate people. It was a studio loft building: artists, painters, second story men.

(Laughs)

Shoplifters, panhandlers. A very eclectic group of folk. We all dwelled there. Some people were official residents, and some people crashed there, you know what I mean?

Where was this at now?

1430 South Penn Square. Right across from the Catto statue, just about.

Oh, y’all was down there. Right across from City Hall.

Yeah, no longer exists, that building. It was a studio loft building, maybe three or four stories. Before, remember they had that fire, people got killed in some kind of a high rise. That’s no longer there but there’s something else there now. It was right there. But we all—Richard Watson, Charlie Pridgen, all these different painters, and Walt[er] Edmonds, and Joe Bailey, he was a sculptor, and James Gadson. And all these folks.

Leo [Gadson]’s brother.

Yeah, Leo’s brother, one of his brothers. So, we were avid, and Norman Connors and Billy Paul—Norman would practice every day, all day long, you know what I mean; on drums, he was like one of the best drummers to me when he left Philly to go to New York. But we were anti so-called sellout, where we call it, you know, playing R&B music. But what happened was, Norman and I, we were in New York together. Norman, Linda Sharrock—Linda Chambers—we moved to New York. A guy named Ron Myers, he says Uncle Paul Myers had the Aqua Lounge, the jazz club in West Philly. So Ron, he had what we called an old bomb type car. And we was going in New York, and he was trying to race a hot rod and blew a gasket. So we wound up in Hightstown, New Jersey, stranded. So we went to a Travelers Aid and we got tickets to go to New York, Greyhound, we got up there. So we was there like refugees. So we go there, we’re just hanging. Norman and Linda stayed, I came back to Philly. You know.

So we lived for the music. Although we danced. We partied hardy. Robert Kenyatta, Gerald Roberts, and Norman and us, we all did that stuff. We met Gerald yesterday.

Yeah, he was telling me about the place across from City Hall.

1430 South Penn Square; Jackson and Cross was the realtor. And in fact, it was an experiment, looking back on it. The audacity of these Black cats being in there, having integrated stuff going on, parties. And right under the nose of Rizzo at City Hall—

(Laughs) Yeah. (Laughs)

Right across the street. We got raided so many times, you know, but the raids, they backfired on them, because they would come through and the person they try to get, got tipped off, so they wouldn’t be there, you know, when the raid went down.

We used to go to a place called the Paradise Lounge, which was 16th and Fitzwater.

Oh yeah. I heard Billy Paul in there.

Billy Paul, right. Norman Connors, Yusef Rahman, the Visitors, a lot of people used to play there on Tuesday nights. It was like a Black Arts Movement venue during that time. So we just played straight ahead. And then, so like, years later I heard Billy Paul and Norman Connors had records out of his hits, on R&B.

So I started saying, there must be something to this, that they would do this. So I listened to Blue Magic’s first album, and the Mighty Love album. Studied stuff. Learned about Sigma Sound Studios, some of the names of people at MFSB, the writers Gamble and Huff and all this. Sigma Sounds was after I self-taught myself a little medley and stuff, went down there.

I met Larry Washington, the conga player, MFSB. He said, “What do you do?” I said, “I play piano.” He took me to Studio B—nobody was in there at that time. He said, “Show me what you can do.” So I played a little medley. He said, “You know what, I got a cousin named Major Harris. They’re going to make a big star out of him. He’s going to need a band.” So that’s how I got in the door.

Wow.

I met other musicians; Sugar Bear, Michael “Sugar Bear” Foreman, Michael 21X “Sugar Bear” Foreman. David 30X, David Cruz, percussionist with MFSB, Sugar Bear’s bass player. Sugar Bear got me the gig with Barbara Mason and the Futures. Back with Billy Paul. And with Teddy Pendergrass, you know.

So. And then I got started loving the Sound of Philadelphia. So it was like part of my DNA.

But the thing with our trio [the Alfie Pollitt Trio, with Alan Nelson and Richard Hill Jr.], is an outlet for me to be able to express myself. Because we’ve had maybe two rehearsals since we got together, over five years. Because we all know inside and out these certain songs. And we just go and we create. And it’s like medicine, healing, for us and the people and everything. But the R&B stuff is so: specific.

If you been to the Uptown Theater, you go hear somebody singing, and stuff is missing from the record and don’t sound like the record, people will boo you and stuff. So my thing was, when I got into the R&B, I was around people like Sam Reed, Bobby Martin the arranger, Bunny Sigler, and we had played stuff the way, close to the record. Roland Chambers, Karl Chambers.

Thom Bell?

Yeah. So it’s a job. It’s like a job, and requires rehearsing and rehearsal and rehearsal. Which can be a lot. It’s a blessing but can be a lot of stress, you know, to have to—just to perfect. But I do a gig, and we just like—yesterday, nonchalant. We come on in and you know, people, they love us and we love them, and hey.

Right, right.

So it’s like a balance.

It’s a very important question, because a lot of people these days that are into Jazz look down on R&B. Just like you said, even back then. If you went over to R&B, or if you did fusion like Norman, they said, “Well, you done sold out, you’re not doing straight ahead, you’re not doing hard bop.” But this, I mean, this is very revealing for me. Because I’ve always felt that R&B is a high art form. Especially the Philly sound. Motown too. But you know, high art. And you just, when you said about the practice and—

Time you put in, and maybe—“Chop that noise!” you know, from neighbors and whatever, what have you.

COMPOSERS, ARRANGERS, AND THE BLACK ROMANTIC IDEAL

I was with the short brother who plays alto, can’t remember his name right now. But we happened to run into him at Reading Terminal. And I asked him about William Hart Muhammad. And he said, he felt that William Hart Muhammad—

Oh, you mean Foster [Child]?

Foster! Foster. Foster.

I met Foster through Byard. He was one of Byard’s young boys.

And Foster said that he believed that William Hart Muhammad is our Pavarotti.

Okay. I think I can relate. I know Russell, he was one of Russell’s influences. Major influence. Russell studied him a lot. Poogie inspired him to do what he does. So I guess its succession would be William Hart, Russell, and then Ted Mills of Blue Magic—they came over later.

Could I ask you about Thom Bell? Because I feel he takes too much credit. But a lot of people think he’s one of the greatest producers and arrangers. Now I know he had a big hand in the Stylistics. But I feel that Poogie—it’s like sometimes if you get the sense that Thom Bell made Poogie. And I’m thinking that Poogie made Thom Bell.

Mm, ok. My spin on this is. According to Thommy and I talking—we met when we were children; Thom Bell. I would say one of the greatest arrangers.

Okay.

The thing about Thom Bell arranging was he would get the conception of everything. Full. And write everything down. Earl Young said you couldn’t work during a Thom Bell session unless you could read. Everything was written. The tambourine part. The oboe part. All the string parts, All the piano parts, you know, was written.

When Thom Bell was inducted into the American Songwriters Hall of Fame, he’s doing a medley of pieces that he’s either written or played. But he’s playing, and singing. He’s a great singer. Everything he’s playing, and it’s like—I said, it’s got to be Thom Bell. Because everything he’s doing, he’s reading. He has a page turner, you know. So whatever that myth, it was dispelled, whatever the myth was. He said everything gotta be written, you know.

Remember that song “Life is a Song Worth Singing”?

I was listening to it just this morning.

Oh, you listen to the arrangement on that? Him and Linda Creed wrote that song, and, well—he did it on Johnny Mathis. I mean, Thommy. Thom Bell, from what I understand, he was asked by Gamble and Huff to be a partner of Philadelphia International Records. But he wanted the independence to be able to just focus on arranging, production and stuff. And so he was an independent guy.

I’m glad you clarified. That Thom Bell is one of the greatest arrangers. I’ve heard other people say it, but I didn’t believe it.

Well. Another great arranger was Bobby Martin. Bobby did “Me and Mrs. Jones.” He did “The Sound of Philadelphia.” He did “[Got My] Head on Straight.” He did “Thanks for Saving My Life.” So much stuff. Bobby Martin. See, Bobby played with Lynn Hope. Lynn Hope was a saxophone player. Bobby played vibes with him.

You ever heard that song “Back in Love Again” by LTD? That’s his arrangement. I mean, so much—The Manhattans stuff. And Joe Simon. And MFSB and, so much stuff.

We had two great arrangers. Simultaneously. Matter of fact, some of the first Philly International stuff that came out was two arrangers, Thommy and Bobby, on “Backstabbers.” Both of them, co-arranged on that. And a few other pieces too, you know what I mean.

Great. I mean, like Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. You heard of him.

(Laughs) [Du Bois’s] The Immortal Child.

On that level, you know what I mean.

Really? Samuel Coleridge. You put him on that level?

That’s where I put him.

Damn.

I mean, I got the rights to say that.

You got the rights, yeah. Wow. Alfie.

See, my father introduced me to Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. My father played cello in the Philadelphia Concert orchestra. Black Symphony Orchestra in Philly, which existed from the ‘30s to the ‘60s.

We’re trying to refresh ourselves on Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. It’s what Du Bois wrote about in “The Immortal Child.” Instead of being snuffed out as so many colored children are, the right chances allowed him to become such a great composer. Pianist. But then he worked so hard that he passed away at 37. He was also born in Britain, which is also interesting, in the Du Boisian period. But that’s even a forerunner of all of these great musicians.

It’s a blessing that we’re able to share and tell these stories.

Now dig this here. Coming up man—cats like y’all, man. ‘Cause y’all got words and this and that. But see. Over time, I’ve been blessed to be able to open up. Tough job, somebody got to do it. Why not oneself?

I find it so fascinating that you put Thom and Bobby Martin in the thing with Samuel Coleridge Taylor.

And Tom Washington, the arranger for Earth, Wind & Fire. Tom Washington, they called him Tom Tom. Tom Tom 84. Quincy. Kashif. Leon Silvers. Prince. Stevie. All these world-class individuals have their own voice and own way of, skillset that—can’t compare nobody.

Like Huey Piano Smith, the guy who did “Rockin’ Pneumonia.” In New Orleans, back in the—that stuff, and the doo wop stuff.

The doo wop stuff in the ‘50s. Man, that stuff touches so many people and brings generations together, man. I mean, happiness and love, across races and everything, man. It’s a whole of stuff. A lot people, like the Europeans, they’ll say, “Well he’s better than him,” and all that kind of stuff.

Here you have these two musical worlds that you’re in. Deeply in both of them. Jazz: straight ahead and avant-garde. And R&B. And I know it was fascinating for me to hear you talk about, and you said it today, how elevated a musical form R&B is. How great of a musical form. And that Thom Bell, you compared Thom Bell to Samuel Coleridge.

I would say Thom Bell, yeah. As an arranger and an orchestrator.

And I recall you saying last time how much went into composing and producing R&B. And also performing it at a really high level for the people who have come to love the songs and the albums so much and look up to someone like Teddy Pendergrass. You were saying something about how even on a concert level, like if you go to hear that song, and it’s not quite played right, that is actually something—you have to rise to the demands of the people. That anchorage is really special it seems. I feel like I didn’t understand that entirely. How different playing jazz for that audience, playing R&B for that audience. I mean both is for the people, but in really different ways. R&B almost pushes you further in some ways, would you say that?

You ever go to the Uptown Theater back in the day where somebody, you heard their record on the radio. And when they got on the show, it didn’t sound like the record? Yeah, that’s because this R&B, it’s so specific. The ingredients in it. That make, that give that sound. If the pieces are missing, it sounds wack, you know what I mean.

Some people called me, they said they want me to put together a Sound of Philly thing. I said, “Well I got to think it out.” They say, such and such amount: “Can you work with that?” I said, “Not really.” Because if you want these songs and this kind of thing, I got to hire singers. I got to rehearse them. I got to pay the people for rehearsals and, you know, figure out which key, even change keys for certain people’s vocal ranges and what have you, you know. Then, working with some musicians that can read music. And some that can’t. The learning curve to be able to pull that together is, you know. It’s more than a notion.

And if you listen to what Thom Bell did, some of that stuff is just like—for example, the song that him and Linda Creed wrote called “Life Is A Song Worth Singing.” Listen to the illustration of strings and—it just builds. It’s like if you go to the Academy of Music, see the Philadelphia Orchestra. It’s that deep, I mean, as far as the musical events that take place within the music. And Thom Bell. He would not hire any musician, even a tambourine player that could not read music. Because his inspiration was—entire inspiration came to him. He knew what, everything he wanted, and he’d write everything out. And if you listen to his music, it’s so much ear candy. So much stuff happening within it, that makes it. And it’s like, pieces stand on their own, but they all make it, all shake hands together you know what I mean.

It sounds like Philadelphia has made one of the most sophisticated contributions to R&B as a tradition.

An original sound. New Orleans had a great original sound, you know what I mean. Chicago. Detroit. Memphis. New York. Other places, Ohio, all the funk stuff. The Isley Brothers. Roger Troutman. Bootsy Collins. And Catfish and all them people.

Could you say more about the orchestral elements in R&B?

Well, say for example, Thom Bell. I would say, “Dun dun dun—dun da, da da.” At the beginning, it’s like, I think it’s like tuba and celeste. That combination. You wouldn’t hear that—that may be the world’s first, somebody using that combination of instruments in that setting.

Was that Stylistics, “Break Up to Make Up?”

Right right, and that’s one of the songs him and Linda Creed wrote as well.

Why did he put those two together?

Because he’s Thom Bell; that’s what he chose to do. I mean, you know, I’m glad he did.

I wanted to ask if you could name a few artists and musicians that inspire you in the city today.

Who are living now?

Who are living now.

Living now, hm. Who’s around now? Odean Pope. Fred Joiner, he played trombone with MFSB. He doesn’t live here but he’s around, he’s still with us. Mother Father Sister Brother Band.

Oh, I never knew that’s what it stands for.

Yeah, and then there’s another spin on it too. But we won’t go into that. (Laughs) Mother Father Sister Brother Band. ‘Cause it was, some of the musicians were string players from the Philadelphia Orchestra. And you had women. You had men, you know. You had R&B. And so-called Western classical people as a family. Musical family. To create those, with the arrangers like Thom Bell and Bobby Martin and others, and Norman Harris, and Roland Chambers would create this music for them to play, and it had a unique, yeah.

Did Billy Paul always sing R&B?

No, back then he was singing jazz. I think he said that one of his main influences was Little Jimmy Scott. And then like, you know, he liked Charlie Parker.

That’s interesting. Look, Little Jimmy Scott was a man who sang like a woman. He sound like Dinah Washington. Because if I could just—didn’t Little Jimmy Scott, wasn’t his role models and singing seemed to be like women like Dinah Washington?

I never really studied his—I can relate. Like Luther Vandross’s models were women, Dionne Warwick, you know.

So Billy was influenced vocally by Little Jimmy Scott and otherwise by Charlie Parker.

Well, like jazz; the jazz scatting, and bebop and all that stuff, sure. See, ‘cause back in the day there was some musicians, singers, that could sing with so-called jazz people and then some that couldn’t. But he was like, it was organic, it was natural. It wasn’t like “I’mma sing like this today,” you know, just to be doing something and not really have solid roots, a foundation with that.

Could I just ask another question about Billy Paul?

Go ahead.

‘Cause you influenced them when you were riding back from New York about Billy Paul.

Oh yeah. Y’all like—what’s the name of that song?

(Singing) July, July, July, July.

There you go. Y’all supposed to say it in unison. Come on, now.

July, July, July, July / Oh me oh me oh my.

And see, like. That song is the sound of Bobby Martin’s arrangement. You know what I mean. It’s like, it’s just classic.

Just say a little more about Bobby Martin.

Well, you ever hear the song called “Back in Love Again?” By LTD. Dun dun dun dun, dun dun. Every time I go around / Back in love again. Jeffrey Osborne, for LTD. That was one of his arrangements.

“The Horse”—the flip side of “Love is All Right.” What’s the guy’s name; Cliff Nobles. It was an early Philly R&B record, you know. It had a flip side, “The Horse” was the instrumental version, of just the instruments, no singing. But the same song that’s on the other side with Cliff Nobles, who was from Norristown, singing lead on it, you know, the lead singer.

But it’s like supposedly the first MFSB, a song wherein the feature is just the musicians, what they did, you know. Without any specific melody. Just like MFSB. You take away all the vocals and you hear all the percolation of different instruments and working together and grooving and everything.

Bunny Sigler was a singer. But he’s also famous for writing some important songs for Patti LaBelle and other people.

And other people.

What are some of the songs he wrote?

“Stairway to Heaven,” O’Jays. “Your Body’s Here With Me (But Your Mind’s On the Other Side of Town).” “I’ll Be Around,” The Spinners. “Somebody Loves You,” he did that on Patti. “If Only You Knew.” And so much stuff. He didn’t really get his due. For all he did. He could have been like a Frank Sinatra, or something like that.

Even as a singer.

Man, he out sang just about everybody I know.

Really.

So, Bunny. I mean, I used to be down at Philly International with the songwriters, and you know, so I kind of learned some of the formula of how to write a song and stuff. I just got some, started feeling some confidence; I would ask different people to sit, to collaborate with me. So I was blessed to do a song with Phil Terry of The Intruders. He’s the only surviving Intruder. We wrote a song together. And I hit up on Bunny. So we wrote a song. It hasn’t come out yet but it’s—he sang, oh, man. He did all the leads and backgrounds.

Also, he did Othello. In Italy.

Othello.

Othello, in Italy. The people hired him over there to come over there, and he did that.

Did the musical?

He sang.

Sang. This is blowing my motherfucking mind. Bunny.

Watch your mouth.

(Laughs) Walter.

Seriously. He was a great talent.

Our interview of Alfie Pollitt, which took place over two sessions in July and September of 2024, was conducted, transcribed, compiled, organized and introduced by Anthony Monteiro, Michelle Lyu and Kathie Jiang.

- Giuseppi Logan was originally born in Philadelphia, but moved to Norfolk when he was young. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Linda D Martin Cancel reply