I was queer. And when other people told me they were queer, I felt a tender pride for all of us. Together, I believed we were courageously transgressing constrained ideas of who and what a person could be. I was convinced we were the next wave of young radicals advancing the frontier of human development.

I grappled with the question of my queer identity for many long months, and ultimately accepted I was queer because I lived with a wider vision of love and human embodiment greater than those dictated by the normative gender roles of Western civilization. Like many other young people, I felt I wasn’t just another straight, heteronormative person. How could I be merely a woman, when I often felt profoundly masculine — protective, aggressive, confident and ambitious? How could I be straight when I gravitated to the utter beauty and greatness of the women in my life?

I felt I could only express the depth and complexity of my love and relationships with the people in my life through the label of being queer. I began to adopt the use of gender-neutral pronouns, and I began to feel the sting when strangers assumed I was a woman. I saw myself as more complete and complex than a woman, both feminine and masculine, and in my androgyny assumed queerness.

But was I? For what does it existentially mean to be queer? Among the many definitions of queerness are assertions that queer love is revolutionary, redefines family, and rejects assimilation into heteropatriarchy. The definition is amorphous, with no scientific and universally accepted categorization. The most universal characteristic of queerness is perhaps that it cannot be succinctly or concretely defined. Moreover, it is scarcely questioned or critiqued by young people, liberals, progressives and radicals alike.

Meanwhile, I cropped my hair short, dated polyamorously, danced and indulged at magnetic, burlesque queer parties. Life voraciously pulsed to the beat of my queer fervor; in my new identity I felt young and liberated. But on quieter nights, hesitation and unrest surfaced as I contemplated my queerness; I could not fully untangle it nor was I certain it truly described me. Something regarding my use of gender-neutral pronouns, which I now often shared when introducing myself, struck me as artificial and self-centered. And when I engaged with ordinary working people, they often did not understand nor connect to my use of specific gender pronouns. Were they transphobic and backward, or was I missing something critical?

Mentors and friends tried to explain me to myself through my identity categories. When I confided in them regarding my struggles and disappointments, I was often told the difficulties in my life had arisen largely because of my multiple marginalized identities. I felt myself reduced to a woman, an Asian, a queer person, or a queer Asian woman — a series of labels instead of simply a person. In claiming these labels for myself, I felt I’d lost something sacred and essentially human in me. W.E.B. Du Bois writes,

“In fact no one knows himself but that self’s own soul. The vast and wonderful knowledge of this marvelous universe is locked in the bosoms of its individual souls. To tap this mighty reservoir of experience, knowledge, beauty, love, and deed we must appeal not to the few, not to some souls, but to all. The narrower the appeal, the poorer the culture; the wider the appeal the more magnificent are the possibilities.“

“Infinite is human nature. We make it finite by choking back the mass of men, by attempting to speak for others, to interpret and act for them, and we end by acting for ourselves and using the world as our private property. If this were all, it were crime enough—but it is not all: by our ignorance we make the creation of the greater world impossible; we beat back a world built of the playing of dogs and laughter of children, the song of Black Folk and worship of Yellow, the love of women and strength of men, and try to express by a group of doddering ancients the Will of the World.”

Studying the legacy of the past freedom fighters and the great Black Freedom struggle profoundly moved me, heart and soul, and led me to draw new conclusions about my place and purpose in the world. Today, I know I was and am not queer. I can now see that I loved the people in my life for their humanity, and that I sought revolutionary truth. But this did not make me queer, for queerness is a theory, attitude and choice rooted in an ignorance of and escape from the mass of humanity.

A Time of Identity Politics

We live in a time of identity politics, when individuals proclaim moral authority on the basis of their identity. This phenomenon has burgeoned in recent years, and continues to ascend in influence among students, activists, progressives and liberals — primarily young, educated American people. Slogans such as “Queer people of color to the front” and “My existence is resistance” are commonly encountered.

University politics are largely characterized by identity-based groups and coalitions. Upon arrival on campus, curious and empathetic Asian, Latin American, Black students are siphoned into their respective single-issue groups; white students throw themselves into a singular cause of their choice: often labor, queer or environmental activism. The impassioned flames and urgency of such activism rooted in identity politics often diminishes once students graduate, because it is not a framework that has been able to transform the hearts, minds and souls of the students. Additionally, students fail to see that they are imbuing an ideology dispensed by the elite institution and rooted in white supremacy. Identity politics is propagated on university campuses because it serves and preserves the interests of the ruling class by encouraging individuals to myopically seek accommodation within the institutions they are a part of, within society’s decadent and degrading order. A larger sense of the great world and its complete history is washed away, the struggle to transform our world into something entirely new and free is quietly lost.

Like fish in water, young educated Americans cannot fathom how fundamentally white and western their assumptions and understanding of the world are. For many of them, identity politics is the only political action they have practiced. Yet there is an alternative. A rich and distinct history of student activism arises from the Black Radical Tradition and Civil Rights Movement, but is scarcely understood by today’s younger generation. Students of this older generation partook in political struggle through movements that were defined by discipline, sacrifice, and a love for the people. Their political practice did not center on the individual self, but rather connected oneself to the greater overarching sweep of humanity. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly,” wrote Martin Luther King Jr.

The Rise of Identity Politics and Intersectionality

Intersectionality, a theory which stems from identity politics and Black feminism of the 1970’s, states that ending one form of oppression requires ending all other forms of oppression. It puts forth the practice of building coalitions between organizations and communities rooted in different oppressions and seeks to unite separate struggles on the assumption that systems are interconnected and profoundly influence one another. However, it fails to complete this connection because of its fixation on individual exceptionality, and thus cannot organically unite people on the basis of our common humanity.

The rise of identity politics is often credited to the Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist group founded in 1974. Their April 1977 statement, which formulates the “triple oppression” of race, gender and class oppression, has risen in influence at institutions and among young educated people. An excerpt from the statement reads, “We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work. This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.”

Despite its sincerity, the statement betrays an entitlement to the spoils of whiteness. Genuinely struggling for all people comes at the price of giving up the status and decadence conferred by the white and western imperialist order. Therefore, freeing all humanity from oppression demands that people give up their white aspirations and yearnings for affirmation and assimilation into western structures. In striving for a new world, it is necessary for people to build a new moral standard on principles of humility, love and discipline, by which to hold themselves and others.

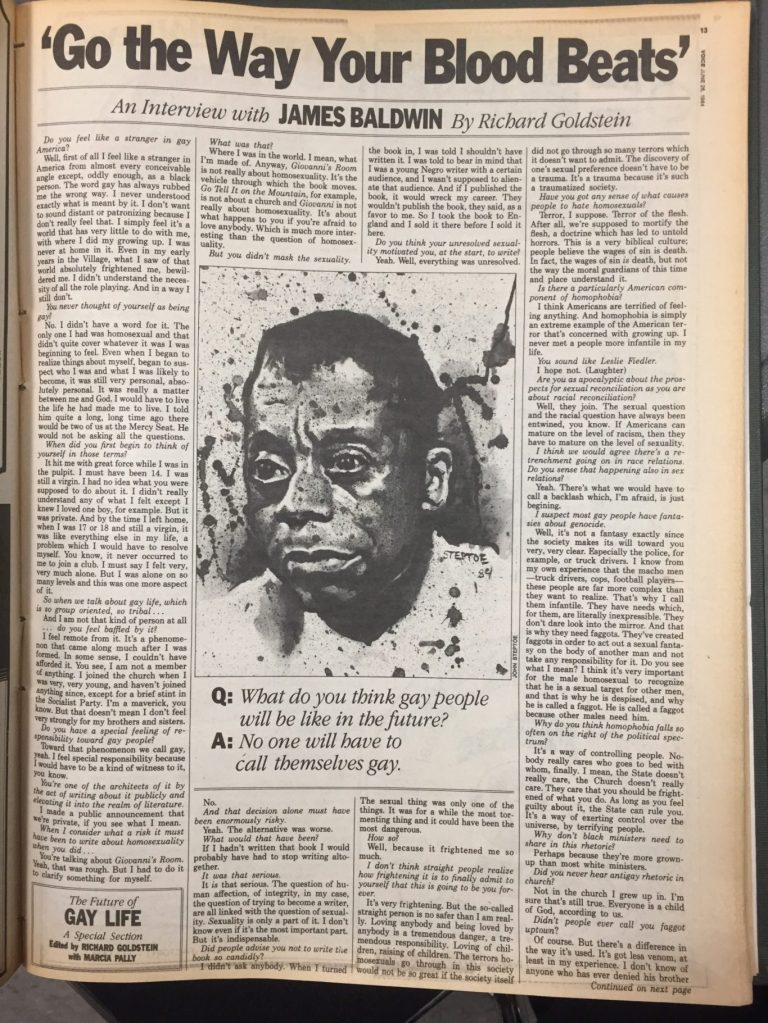

Identity politics is also known as a politics of recognition, or politics of inclusion. Those who follow identity politics organize around the right to be accepted by the ruling hegemony. They cannot seriously theorize a new system in which all people are free, which transcends the dominant structures and principles we have been given and therefore in which identity categories would no longer be relevant. “I think white gay people feel cheated because they were born, in principle, into a society in which they were supposed to be safe. The anomaly of their sexuality puts them in danger, unexpectedly,” Baldwin said of the gay rights movement in 1984, “Their reaction seems to me in direct proportion to the sense of feeling cheated of the advantages which accrue to white people in a white society. There’s an element, it has always seemed to me, of bewilderment and complaint.”

Whiteness and Our Shared Humanity

Identity politics cannot be the basis of revolutionary struggle, because such a political theory is a form of whiteness. Whiteness is not defined just by skin color, but also by how one relates to oneself and the rest of the world’s people. Whiteness characterizes a deep nihilism and an infantile urge to be superior to the rest of humanity. It fails to see and respond to reality, and fearfully recoils from the truths of white and Western civilization. It manifests as inescapable despair, an existential lack of purpose and direction. It is arrogant, ignorant, self-deluded and self-centered. It is the ideology that we inherit from White America, that is reinforced in our media, our universities, our workplaces, that as young Americans we must struggle to overcome if we seek to transform the world.

“But what on earth is whiteness that one should so desire it?” Du Bois asks in his essay The Souls of White Folk. Du Bois clarifies what appears to be a gaping contradiction of society. What is whiteness after all, such that people will clamor over one another to achieve their white aspirations? After all, becoming white comes at the great cost of shedding one’s sense of humanity, morality and reality. And so what is queerness such that one should so desire it?

“Then always, somehow, some way, silently but clearly, I am given to understand that whiteness is the ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!”

This craving for dominance is the attitude beneath whiteness and queerness. It is an attitude that produces the urgent, pained insistence on the part of many queer individuals that their queerness be known and that their pronouns be correctly applied by all. It is an attitude that compels young individuals to feel ‘seen’ and existentially validated. Beneath is a craving for safety, to find comfort in the white world instead of taking responsibility for changing it.

What drives those who follow identity politics to prioritize the ways in which they are distinct and exceptional? The existence of differences between all people is a basic fact. The central question is not truly one of difference therefore, but rather one of responsibility. We all share a responsibility for shaping the world for future generations. We can retreat into self-righteousness and evade this great responsibility, or we can emerge from self-obsession and forge a new identity based in selfless revolutionary principles of discipline, sacrifice and love for the people.

If you were to encounter a white man, perhaps affluent, arrogant and ignorant, what would cross your mind? Would you think of how you face more hardship and are therefore more advanced and morally entitled than him? Or would you notice his existential despair, which certainly lives in him, and see it as a mirror for your own existential struggle? Would you feel a sense of kinship or responsibility to this man?

Because identity politics is largely defined by division and exceptionality, placing certain individuals morally above others on the basis of discrete identity categories — frequently brandished like a collection of badges — it fails to accept the simple fact that we are human.

I had failed to accept the simple fact that we are human, had failed to see that in our common humanity we share something sacred, something which we must defend, nourish and develop. I thought I needed queerness to describe the silent wonder of observing a stranger’s human beauty, the tender kinship of being reunited with a good friend, the budding tears of contemplating my parents growing old. The love I felt for the people in my life was not a queer love, but rather a striving for what King calls agape, a love for humanity.

“Agape means understanding, redeeming good will for all men. It is an overflowing love which is purely spontaneous, unmotivated, groundless, and creative. Agape is disinterested love. It is a love in which the individual seeks not his own good, but the good of his neighbor.”

The Confusion of Identity

Of all the identity categories, queer identity is the most pervasive and authoritative among young educated people today. It is not an identity that one is born into, but rather, a framework that one can select for oneself. It is a moral choice. For many individuals, it is not a direct reflection of one’s sexual orientation, but rather an attitude toward oneself and society that is believed to be transgressive.

The choice to call oneself queer is often a profound, difficult and existential process during which an individual questions the foundations of their place in the world and how they relate to other people in society. Adopting a queer vision of the world is believed to produce clarity, radicalism and a more honest understanding of the world. Yet, it produces the opposite. A deeper angst, uncertainty, and depression often complements those who most ardently assert their queer identities.

It is ironic that a process meant to produce clarity for oneself instead produces dread and confusion — such is the trap of whiteness. Identity politics does not just keep individuals safely contained within a white relationship to the world, it deepens and even elevates their position in the white world.

What is needed for our times is not queerness nor a feverish obsession with our identities, but rather a tradition that helps us envision a new world and a place for ourselves in society on principled terms. To achieve this demands that we define ourselves beyond the white imagination.

Although identity politics produces a critique of the ills of a collapsing Western civilization by drawing attention to the hardship faced by numerous communities, it does not pierce the root of these problems. What identity politics believes is a problem of the marginalized few, is in fact a collective plague of American society.

“The terrors homosexuals go through in this society would not be so great if the society itself did not go through so many terrors which it doesn’t want to admit. The discovery of one’s sexual preference doesn’t have to be a trauma. It’s trauma because it’s such a traumatized society.”

James Baldwin had no interest for labels such as “gay,” which he understood as terms of the oppressor which confined and controlled human potential. Despite being a gay Black man, he sought to define himself and others by the principles of shared humanity. “There’s nothing in me that is not in everybody else, and nothing in everybody else that is not in me.” By recognizing the human potential of all people, Baldwin saw the world through eyes of a brave and humble love, and understood others through the highest form of love, agape.

Becoming Human, Our Responsibility

“I have met only a very few people—and most of these were not Americans—who had any real desire to be free. Freedom is hard to bear. It can be objected that I am speaking of political freedom in spiritual terms, but the political institutions of any nation are always menaced and are ultimately controlled by the spiritual state of that nation. We are controlled here by our confusion, far more than we know, and the American dream has therefore become something much more closely resembling a nightmare, on the private, domestic, and international levels. Privately, we cannot stand our lives and dare not examine them; domestically, we take no responsibility for (and no pride in) what goes on in our country; and, internationally, for many millions of people, we are an unmitigated disaster.”

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

As Baldwin writes, freedom is hard to bear, because struggling for freedom demands discipline, honesty, humility and sacrifice. There is a profound necessity for those who seek to change the world to grow into greater, more moral and spiritually complete human beings, leaders who can take responsibility for the future of all humanity.

However, identity politics cannot provide revolutionary development. It cannot escape its obsession and orientation to the self; it clings to entitlement and self-righteousness. Jimmy Boggs said, “Being a victim of oppression in the United States is not enough to make you revolutionary, just as dropping out of your mother’s womb is not enough to make you human.” Ultimately, identity politics is a political tradition which does not confront the white, western values we have inherited. It is a masking of the contradictions of Western civilization, an assimilation to the status quo and an escape from the need to become a transformed human being.

Alternatively, revolutionary politics arises from a selfless relationship to the world and its people. A desperate clinging to self-identification and emphasis on individualism begins to fade when our hearts are welded to the spiritual strife of people, their struggle to flourish and fulfill their human potential — when our minds are set on the vast horizons of tomorrow and the incredible potential of people to transform into revolutionaries. Identity politics would encourage us to shrink away from this society and its people, but I want for us to stay and struggle, to face ourselves and grow, for what we shall seek is the freedom to change our society.

Further Reading

- James Baldwin, 1984 Interview with Richard Goldstein

- James Baldwin, Letter From A Region In My Mind

- Grace Lee Boggs, Living for Change

- W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk

- W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of White Folk

- Martin Luther King Jr., An Experiment in Love

- Martin Luther King Jr., Letter From A Birmingham Jail

Leave a reply to stew312856 Cancel reply