Publication date: 2006 | First published in CLR James Journal

Note: This essay emerges from a period in Dr. Monteiro’s ideological remaking and exploration — starting in the 1990s with the collapse of the Soviet Union — when he rethought the role of Marxism and increasingly identified Du Bois as the central thinker for the 21st century. The essay captures his work on philosophical concepts of time, being, and logic grounded in Du Bois and the struggle for freedom.

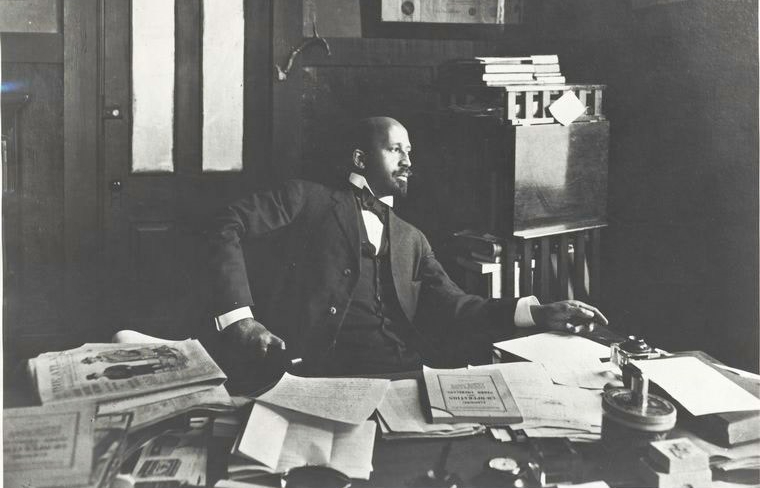

This paper is an effort to theoretically grapple with African complexity; it proceeds from the assumption that African Being is culturally, sociologically, historically, genetically and civilizationally complex. I attempt to use the theoretical breakthroughs in natural science theory and new thinking in the social and philosophical sciences to explain this complexity. Theories in the areas of evolutionary biology, chaos theory, population genetics, relativity theory, quantum mechanics and string theory are what I work with. However, I attempt to discover synthetic and synergetic relationships between these theories and social and human science theories; in particular, theories of social structure, existential phenomenology and psychoanalysis. I use the works of CJ Munford, Lewis Gordon, Hortense Spillers and Paget Henry to illustrate these efforts within the area of African American Studies. At the same time I pay close attention to the philosophical and theoretical efforts of Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre and Edmund Husserl. All of this occurs within the framework of the revolution in social and human science initiated by W.E.B Du Bois; especially his notion of the Color Line and the racialization of human relationships.

Du Bois in the early part of the last century discovered a parallel, if not alternative, phenomenology to that developed by Husserl. Du Bois’ was an historical phenomenology. Time, in this Du Boisian construal, is inherent to the phenomena being studied. We see in Du Bois at least two understandings of Time. First there is phenomenological or contingent Time, Time that is existential. Secondly there is teleological, or purposeful Time, Time that has a logic which supercedes phenomena, this is macro historical time. These distinct Time modalities allow for phenomena, especially racialized phenomena, and especially the African, to be viewed in generative and anticipatory modalities, and has manifestations of both the past and present, but significantly of possible worlds. In this respect Du Bois confronts us with a complex logic of Time and the dialectics of Time within the framework of African existence.

Time in these senses is not abstracted from, but is profoundly implicated in race. The entanglement of Time and race is a profound and not yet unexplored dimension of Du Boisian thinking. Race decenters Time, bends it, existentializes it. At the same time, race anchors Time, especially as macro historical Time, to a racial logic, and a racial telos. The logic and telos of race complexifies Time. In this sense, this essay looks at Time in a Du Boisian sense. The racialization of human relationships complexifies them. Significantly it complexifies Time, forcing a phenomenological reduction and a setting aside of our natural orientation to Time. The African exists within this profound complexity. African consciousness both masters and is mastered by these complexities. Du Bois’ historical phenomenology attempts to grasp this reality. This essay is Du Boisian in that it views Du Bois not primarily as an historical figure, but as a working enterprise. Hence, it builds upon the epistemic rupture that is the Du Boisian oeuvre.

Scholars have rightly argued that W.E.B Du Bois over the course of his intellectual life changed his position on race several times. His initial statement in 1897 at the founding of the American Negro Academy is found in “The Conservation of Races.” Here, in its deepest sense, Du Bois asserts African Being as an historically constituted civilizational species; albeit Othered by white supremacy and not yet conscious of its place in modernity. Other iterations are in his report to the first Pan African Conference in 1900 where he asserts that the Problem of the 20th Century is the Problem of the Color Line and then again in 1915 in the book The Negro where he links all Africans to ancient Egypt and in Darkwater, especially in the essay “The Souls of White Folk” he shows that the racialization of Africans is a recent thing and is connected to the Slave Trade and plantation slavery. He asserts the color line and racialization were successful because they were profitable.

Du Bois’s oeuvre shows his attempt to scientifically understand what was in effect a dynamic phenomenon, the African under conditions of European hegemony. Being that exists in a state similar to what Stephen Jay Gould calls punctuated equilibrium. I will deploy the conceptual frameworks of several bodies of knowledge and their linguistic repertoires to understand this polymorphism. This language fits the realities of Black historically constituted realities and augments fictive, existential, literary and psychoanalytical modalities. This is not to eschew these explanatory modalities and their linguistic and conceptual repertoires, but to insist that at explanatory levels beyond the individual and mid and meso levels of social structure and structural formations, robust explanatory possibilities occur using concepts such as polymorphism, dynamic equilibrium, punctuated equilibrium and far from equilibrium dynamics. However, it must be stated that these concepts apply to a research program in black studies that is strongly historical and that looks at macro-historical processes. At the same time I argue in this essay that social theorists have shown how various explanatory modalities can be synthesized. For instance, the existential concern with time and Being is not unimportant in thinking about the individual. Yet, when addressing macro-structural concerns the existential modality has to be considered within the framework of larger structural and historical modalities. However, African Being is temporal and historical. I agree with Heidegger that Being is in the world, it is social and not isolated and that Being is not essence, but potentiality or possibility. In the way I am using the notion African Being it is as a generative category, explaining a wide body of concrete historical existences and African possibility, in this sense resistance leading to liberation.

Africans, or African Americans, are not a collection of individuals, i.e. an aggregational group, but a historically constituted collectivity. They are constituted in history and when viewed as an historically constituted collectivity they can be understood from a macro-historical level. I recognize that this is but one, and perhaps the first approximation to a more complex understanding. Which is to say that by understanding the historical constitution of Africans, does not end the process of scientifically understanding Africans.

Ideas of time, being and space will inform my approach. There are several significant bodies of philosophy that can be appropriated to this project. Among them are classical works within the field of existentialist philosophy. Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness are valuable because of their explorations of the time and being dialectic at the level of the individual’s encounter with the moment, or the epoch. However, at the macro-historical level Hegel’s Science of Logic is unavoidable. Hegel’s profound impact upon historiography, especially as it concerns history as a dialectical process can inform many efforts at investigating African and African American Being as historically constituted through a dialectical process. Fanon’s sociogeny or sociogenetic analysis, is acutely attuned to time. Speaking in Black Skin White Masks, he says, “The architecture of this work is rooted in the temporal. Every human problem must be considered from the standpoint of time.” Ian Hacking’s uses of Foucault are helpful interventions into our understanding of micro-historical processes, locating and situating the observer. Molefi Asante’s Afro-centrism is a postmodern situational or location theory. Centrism in his understanding is a way for the observer to locate for her/himself the appropriate angle for engaging the objects of analysis. Husserl’s idea that Europe faces a civilizational crisis could be read as a call for a new and revolutionized discourse and a new form of Eurocentrism. Spillers, similarly demands a new African American feminist centrism emerging from the crisis of blackness during slavery and after produced by the invincibility of the Black female. Indeed, it is African Being and Time in the historical space of European hegemony and African/African American resistance that is the context of this inquiry.

My angle of investigation is ideologically anchored to Black liberation and theoretically committed to a synthesis of multiple theoretical perspectives; social theoretic and explanatory issues connected to the project of African and African American liberation. I attempt a synthesis of the historical, temporal, existential, phenomenological and psychoanalytic. I do this using the works of CJ Munford, Lewis Gordon, Hortense Spillers and Paget Henry. To do so demands an interrogation, if not a complete break with notions of progress as asserted in European thought since the Enlightenment. I, therefore, attempt to transgress, problematize and subvert the comfort zone of time as assumed in European centered historiography and social theory.

There are important existential interrogations of the modern European concept of time and progress. However, the natural sciences from relativity theory and quantum mechanics to evolutionary biology and population genetics interrogate time. A very significant contribution to this is Stephen Jay Gould’s work, especially his magnum opus, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. What I suggest about the particularity of space-time realities as they are encountered in socio-historical time and socio-structural time, Gould calls time tiering. He insists that from a theoretical standpoint such recognition allows for both macro-structural and phenomenological levels of investigation. His point is that not only does time express itself differently dependent upon the structural level being investigated, but that we encounter distinct modalities of time in the course of scientific investigation. Time tiering is necessary in understanding stratified and racialized social structures.

For those working in the fields of Africana social and human science and who are compelled by the polymorphous nature of African and African American Being to examine multiple layers of time in the context of social and racial relationships, this is what we might term social time tiering. From an Africana standpoint several, though not all, possible time considerations are macro historical in nature: macro-structural time, existential and phenomenological time, mythic time, magical and surrealistic time. This engagement with time requires a new understanding of time, being and space within Africana social and human science; one which recognizes the malleability not just of space and being, but also of time. But which understands that Being and Time interact with space in ways that in the case of African Americans and Africans produces a type of polymorphous being, rather than an essentialized and consequently ahistorical being. Acknowledging this does not negate the fact that discrete structural levels and specific structurating processes adhere to distinct time modalities and rhythms. Time, then, is a complicated measure of socio-historical, structural formative, intersubjective, individual and existential movement. It is further complicated because it, conceivably, varies between groups based upon their place in the social system of domination and their status as oppressed or oppressors. To say this is to say that time, like social structures, is plastic.

Problems of time conceived within the framework of polymorphous Being requires that time be viewed as dynamic and plastic. Time as a measure of social Being, or better, African Time as a measure of African Being, suggests that with all things time is a variable quantity. However, there is yet another investigative region that concerns logic. We might refer to this as the logic (or perhaps logics) of time, being and space. Here we enter into the problems understood within the realm of dialectical logic. When engaging levels of socio-historical being we confront distinct logics inherent to the structural level being investigated. For instance, the logic of race relationships, the logic of African American liberation, the logic of globalization and imperialism, the logic of structural formation of systems of domination. These logics have their own dialectics. They, from a dialectical standpoint operate within larger historical dialectics and interact with lower and higher dialectical logics. We can, therefore, speak of dialectics within dialectics. The project to explain African American and African Being is part of the epistemological engagements with dialectical reasoning; compelling a complexification of the project. We end up turning and inverting the objects of investigation, and subjecting them to multiple angles of observation, differing levels of dialectical interrogation, distinct structural levels and structuration processes and time tiering. This can involve everything from choosing novel theoretical positions, such as using new theories in macro-evolutionary thinking to quantum mechanics to chaos theories, or establishing synergistic relationships between the aforementioned theories and existential or psychoanalytic theories. In some ways this might be thought of as establishing mechanisms to explain the complex terrain that is African Being. Or better, to explain the polymorphic nature of African Being. This essay attempts to begin that work within Africana social and human science.

Polymorphism is the state of being where a social or biological species or a substance in chemistry or physics exists in multiple forms, varying as the external situation within which it exists varies. A polymorphic state results from the ability of the same atoms or molecules, for instance, to form any of several stable frameworks in a given space. In terms of human life it is the possibility of individuals, groups, small, medium and large collectives, social structures and institutions, nations, races and classes to form any number of possible forms of being. In social and human relationships the conscious life world is the organizing center of all of these levels of Being. Polymorphism is a dynamic state of Being. It is this dynamism and multiple determinations of the concrete forms of African American and African Being, which situates my manner of thinking about African American Being.

Another dynamic state, which also applies to African and African American Being, is punctuated equilibrium. This theory developed by Gould and Eldridge is a theory of structural change and seeks to measure how time changes (specifically how it speeds up) as species enter a process of transformation or speciation. A punctuated equilibrium moment is one where time speeds up as a species goes through an accelerated process of evolutionary change. It seems to me that this process of rapid social or racial transformation defines African Being in America. In this case we might define the historical period since enslavement as one of punctuated equilibrium; the accelerated transformation of Africans into a distinct Being in the socio-historical environment of North America. This situation, I theorize, produces a polymorphous Being, an African American polymorphous Being. This, I argue, is what Du Bois was attempting to grasp as he investigated the African American.

Polymorphism and punctuated equilibrium look at social structures, their transformations and structuration processes. This includes levels from the macro-structural to the intersubjective and contextualizes the individual within these varying levels of social structure. Within social theory it draws upon a vast body of work that has to do with structuralism, levels of structural analysis, and structuration processes. At the same time I propose that while the structural approach is my starting point it is insufficient in explaining the complexities of African Being. Thus I feel that the Black existentialism of Fanon and Gordon, the psychoanalysis of Spillers, the Africana phenomenology of Paget Henry or elements of the prophetic pragmatism of West are critical parts of explanation.

The philosopher of history, Clarence J Munford proposes a way of examining the African world which he calls civilizational historicism. It is a macro-historical methodology which incorporates historical materialism and political economy into it. Munford eschews existentialism and other forms of methodological individualism for a robust historicism. Munford insists upon a scientific approach and the search for laws, patterns and regularities in history. These patterns can be found essentially at the large level or events as they manifest themselves macro-historically and macro-structurally. Besides macro-structural and macro-historical, one could define Munford’s project as methodological totalism or methodological wholism, which views totalities as organically existing phenomena and thus begins investigation at the level of social and historical wholes.

Those modalities, however, that look at phenomena at levels below the macro-structural or macro-historical are a vital part of explaining African Being. These are levels where the macro-structural phenomena are concretized; as in the lives of individuals, small collectivities, such as tribal groups or rural communities; and, for instance, in macro and meso level structures, like socio-economic classes, class and social fragments, such as the lumpen-proletariat, stranded populations, such as maroon communities, migrant populations and homeless communities and in institutions, such as the racialized state, the Black Church, Negro colleges, political, cultural, business and economic institutions. These structural levels and their structuring modalities carry specific temporalities. Such angles of investigation are worked out in, among others, the theorizing of Franz Fanon, Kyriakos M. Kontopoulos, Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, Hortense Spillers and Lewis Gordon. It is possible to discover moments of compatibility and common practical proposals for these levels of theorizing and robust macro-historicism.

Science figures prominently in this project. At the macro-structural level it embraces three conventional commitments within science. First to truth as discoverable; second, to a materialist and objectivist concept of reality; and third, to a rationalist form of explanation. Side by side with this investment in scientific inquiry is a commitment to history and the historical a priori. The historical a priori is that range of beliefs, values and structures that precede the historical moment to be investigated. They are what could be called structured structuring structures. Once rational explanation references notions such as the a priori we are immediately in the realm of Kantianism and ultimately structuralism. For Du Bois, for instance, the issue is not merely to explain the modalities of rational thought, but to construct a practical way of discussing and explaining racial oppression. Ian Hacking asserts that the historical a priori is that which “points at conditions on the possibility of knowledge.” Using a Du Boisian framework and extending his proposal concerning race, the historical a priori is race and white supremacy. Race and white supremacy are conditions that make possible the structures of the modern and conditions upon which modern knowledge of human relationships is based. Moreover, race in the sense of being a category of knowledge, conditions the boundaries of explanation. That is what Bourdieu calls structuring structures, which overdetermines the conditions of knowledge.

Kyriakos M Kontopulos’ The Logics of Social Structure is a seminal text in demonstrating the multiple levels and modes of analyzing and explaining social structure, structuration and mid and micro-level social structures. He points to the significance of the work of Pierre Bourdieu, especially his Outline of a Theory of Practice. Bourdieu draws the attention of theorists to the possibilities of understanding the behaviors of socio-historical structures as heterarchical rather than solely hierarchical. Bourdieu, moreover, recognizes social structures as dynamic and bound to temporal conditions. He appropriates Marx’s idea of the multiple determinations of concrete historical reality is particularly significant. Marx’s formulation suggests a heterarchical determination of reality. There is a dynamic dialectic sense of things wherein the structuring process, or structuration, takes place through a dynamic process of multiple indeterminacies. Hence, determination through indeterminacies. In this account the strategic intervention of agents, in macro-structural terms, collective agents identified as races, nations, classes and civilizations, are critical to the structuration process. The deep structural level, the level of civilization, is possibly a dynamic structure, which is subject to the logics of structuration and indeterminacy.

Civilizational Historicism and Structural Explanation

Taking the work of Clarence J Munford as an example, the historical a priori is race. Race is the overarching or central dialectic in modern world history. Race is generative and overdetermining, of other events and structures. Civilization, Munford’s deep structure, should be subject to the same possibilities of determination through multiple indeterminacies as are other structures. This possibility seems to be a necessary consideration if the possibility of revolutionary disjuncture is to become a possibility. Indeed, the moment of revolutionary rupture is at this precise moment of instability.

At the level of explanation, race shapes explanation, and perception. Race as an explanatory category sets rules for the explanation of events. Race is, then in this regard, a structuring logic.

Structuralist explanatory modalities can be complicated mixes of history, philosophy and science. Structuralist modalities that are also historical, as in Munford’s case, or from a different angle Jeffrey Schmidt’s, are composed of a three level engagement with objective reality. First, to history as critical to social inquiry. In other words Time and temporality are critical to understanding the dynamics of social structural and socio-historical processes. Secondly, the assumption that history proceeds dialectically and that race, class, civilization or other macro historical phenomena and the conflict of contending forces are central to its understanding. Thirdly, history can be a science; meaning patterns, laws and regularities and cause and effect in history are discoverable. Rather than local, folk or micro-history, Munford believes that macro or global historical analysis is appropriate to a scientific African historiography and to coming forward with practical solutions to this global problem. This epistemology of history differs profoundly from let us say existentialism, phenomenology and psychoanalytical methods of doing history.

At the macro-structural and macro-historical levels a muscular and globalist approach to history is demanded. At lower levels of explanation historical analysis need not be as robust and muscular. Epistemologies such as Cornel West’s prophetic pragmatism, the discursive relativism of Molefi Asante and Lucius Outlaw, the Black existentialism of Lewis Gordon or the psychoanalysis of Hortense Spillers fall among those epistemologies that permit either ahistoricism or mild historicism. Time is most often not a central dimension of investigation or is linked only in passing to the investigation. They usually are discourses on oppression without suggesting logics and praxes to change it. Munford, in attempting to overcome the problem of theory without praxes, seeks to link theory to ideology and social transformation. He eschews methodological individualism, and asserts the centrality of historically constituted collectivities. In social theoretic terms Munford engages historically constituted totalities as the object and subject of history and historical transformation.

This approach I would identify as the Du Boisian approach within historiography and history writing. Du Bois did not merely navigate the terrain of historical facts and events, but was concerned with their organization, interpretation and critique. This is nowhere better demonstrated than in his Black Reconstruction in America. Du Bois’s epistemology was restless and located on the margins of mainstream and hegemonic discourses. From the very beginning of his public career he identified his project and epistemology as African. In a 1904 review of his Souls of Black Folk, he argues he wrote the work as an African. Du Bois, as became clear, not only thought about the world as an African, building an African epistemology, but thought about what it meant to be an African in the world. This he considered not just from the standpoint of the individual scholar, but being Africans in a European dominated world. He grappled with the problem of making epistemology practical and anchoring it to actual worlds of Africans. It centers itself in African Being and Time. In my essay, “Being an African in the World: The Du Boisian Epistemology” I attempt to demonstrate how Du Bois shaped his scholarship as investigations of African Being and African Time. I have argued this represented a transgressive intervention into traditional metaphysics and ontology. In an unpublished paper I suggested that Du Bois was attempting to make epistemology practical. This linking of epistemology to social change for Du Bois occurred through concretizing it and though Du Bois did not state it in this way, linking it to ideology.

Du Bois, for instance, argued that history is propaganda. I take his use of the word propaganda to mean what we would call ideology. He used this African anchorage to organize the field of investigation. This lens situates the investigator in the historical situation of Black oppression and sought to link the researcher to a historical body of ideas and methods of investigation that opposes Black oppression. However, Du Bois was not a theorist of oppression; he was a theorist of African agency and empowerment. He consciously asserts that Africa is foundational to his understanding of himself and the world. Furthermore, Du Bois’s foundationalism commits him to proceed from stated assumptions (in the main the centrality of Africa and African civilization to the construction of the African American), a discrete worldview (African civilization is the origin of world civilization and Africans continue through resistance to give its gifts to humanity) and a stated ideological stance (the crucial dimension of African and African American liberation to human liberation). Lastly, Du Bois constructed a multi-layered approach to knowledge, attempting to capture the multiple determinations of the concrete African realities. This notion of the multiple determination of the concrete is taken from Karl Marx’ Grundrisse. It is worth noting that the turn from a concern with the concrete or the material world as it were and a turn to primary concern with the subjective and psychological is a modality of doing the human sciences most associated with poststructuralism, surrealism, magical realism and certain forms of existentialism. It represents a certain suspension of the concrete in order to better understand the subject of history. An important aspect of this turn is the linguistic turn and hermeneutics.

Historical Ontology and Civilizational Historicism

This leads us to a discussion of historical ontology. I consider civilizational historicism, Clarence J Munford’s methodological and philosophical apparatus, to be a form of historical ontology. I have encountered the term historical ontology in the works of the philosopher Ian Hacking. His is a philosophical investigation of the uses of history in understanding the genealogies of ideas. His project is rooted in a Foucaultian understanding of the contexts and sociology of ideas. The existential philosopher Martin Heidegger precedes Foucault in attempting to understand the historical conditionalities of being and what Hacking calls the historical ontological. Munford inverts the idealist and subjectivist stance of Heidegger, Foucault and Hacking by designating historical Being as historically constituted concrete collectivities, such as races, civilizations, classes and nations. Historical Ontology is a way of speaking about and understanding social phenomenon, as they exist in historical time. Civilizational historicism is a way of understanding African historical Being understood in African historical time. It seems that Munford’s method works best in this robust relativist manner, especially as it links time and Being to the unique and specified historical space occupied by Africans in the epoch beginning with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. However, the historical a priori, i.e. the civilizational dimension, would insist upon pin pointing those beliefs, values, modes of production, culture etc. that precede the African holocaust of slavery and colonialism. Hence, historical evolution and mutation occurs and proceeds under certain predetermined conditionalities. This has produced racialized civilizations. In modern history European cultures and peoples have congealed as a white civilization, which stands apart from the rest of humanity. The racialization of civilizations (not just peoples) is the decisive outcome of the socio-historical processes associated with modernity. Therefore, white civilization, and the civilizational commitment to and predisposition among the majority of the world’s white people to white supremacy, overdetermines the modern epoch. Civilization in practical methodological terms is the totality of those things that are the historical a priori; it is what is considered the deep structure.

What is fascinating about this modality is that methodological complexity and flexibility is what is demanded. Indeed complexity is required by the nature of the object of inquiry. This specific dialectics of African time and Being conditioned by African civilization and its negation, white supremacy and European capitalism is the historical object to be understood. Civilizational historicism tries to avoid the pitfalls of essentialism, so often associated with certain forms of Afrocentrism, while preserving the category essentiality as a part of the understanding of reality and the working up of knowledge. More importantly, what Munford seeks to capture in the historical a priori are those conditions that determine the historical moment, or the historical epoch. The historical a priori of white or European civilization for Munford is white supremacy, on the one side, and African civilization on the other. In other words, white civilization exists as a dialectical relationship between white supremacy and African civilization. In Black Skin White Masks Fanon identifies a massive psycho existential complex, which is European or white civilization. Its existence assumes the African or African civilization, as objects of white history. By removing the African from history as subject or agent you distort her/his historical consciousness, designating it a false or pathological consciousness, or as with Hegel outside of history because the African stands outside world consciousness, lacking human identity. Munford’s project assumes the centrality of what Fanon recognizes as the centrality of Black folk to the existence of the white world system and their centrality to its destruction. Lewis Gordon in Fanon and the Crisis of European Man understands his intellectual project as a disruptive intervention into European consciousness in the Fanonian sense. Gordon believes the study and clarification of Black and white consciousness will be a contribution to the downfall of white supremacy.

Methodological Mutations and Evolutions Within Race Research

There are some who have found Munford’s turn to a sharper focus upon race as the central dynamic in modern world history to be a retreat from his views found in such works as Production Relations and Black Liberation. I am sure that Munford views his work starting with The Black Ordeal and Race and Reparations and Race and Civilization to be further developments of his understanding of history and the evolution of historiography. Race and Civilization does not retreat on matters of a materialist historiography, the uses of political economic categories and analysis nor on his ideological commitments to Black liberation. What we have is an evolution of a project that he started as a graduate student in the former German Democratic Republic. At the same time theories and methodologies mutate and change. This is the history of human thought. These variations and mutations, the processes of ideational evolutions, occur within historical contexts and are advanced as thinkers with specific race, class and national locations mature. The scientific and intellectual maturation of thinkers is a necessary part of innovation within research programs. If nothing else, the logic of the notion of the centrality of Black liberation to world history compels scientific flexibility and innovation. Moreover, all theories should be subjected to regular critique and self-criticism; furthermore, the objects of race inquiry themselves are constantly evolving and mutating. Races, as Du Bois understood, are dynamic historically constituted social and cultural groups. Races are subject to mutations, sometimes quite dramatic ones. Just as races mutate, so do racial identities. Methodologies must similarly evolve and mutate to account for this.

The idea of absolute and unchanged epistemologies and methodologies goes against the grain of scientific and philosophical inquiry. Thomas Kuhn drew attention to this, capturing the mutability and changes of paradigms, including at times the emergence of revolutionary and subversive paradigms. Imre Lakatos spoke of the evolutionary processes whereby research programs and the research landscape experience challenges leading to new revolutionary research programs and new possibilities for thought and research. Munford’s work seems to be part of the evolutionary process of changing the ways we think and do research on Africans. Most often historical research and historical writing proceeds quite conventionally. It is quite simply a narrative, often without explicitly stating its philosophical or ideological commitments. In this respect the historical object and historian are reified. There has been recently a trend to a more existential historical narrative. This modality proceeds often through biography. There is a surrealistic turn where history is a type of narrative about dreams and visions. Some construct Black history and being as encounters with absurdity as a way of explaining Black consciousness in its encounters with white supremacy. Marxist historiography, historical materialism, is more often seen in its influence upon conventional and existential narratives than as a full-blown project.

Each of these stances, at their best, suggests a moment in the attempt to capture the historical object/subject, African and African American resistance. In certain senses each manifests a political moment. In the current situation of scientific and scholarly efforts to explain race and Black oppression the angles of observation have been multiplied. However, the richness of academic discourse is often limited by the convention of seeking to stand above ideology and deep commitments. This is especially the case for Black thinkers who are more closely policed by the academic gatekeepers and thought police in the elite white academy. This desire not to appear to be one-sided lends itself to reification and solipsism. A good part of this goes under the banner of post-structuralism and post-modernism. However, each suspends concerns with the object of history and turns to a single-minded engagement with its subject. A concern with the subject in ways that suggest the only verifiable reality is subjective. Munford’s materialist historiography and his insistence upon the crucial role of political economy in macro social explanation is his way of countering this trend. The turn to the centrality of the fictive in understanding Black realities in some ways suggests this turn. Moreover, the modern ways of constructing the novel using surrealism and magical realism is a way of taking the characters of the novel away from objective historical reality and inventing them out of imagined, sometimes improvised, absurdist realities. Objective history is suspended for the sake of the novel. The concerns are with the characters’ understandings or confusions with their multiple subjective or psychological realities.

Munford’s Structuralism and Lewis Gordon’s Phenomenology: Two Du Boisian Approaches

Among more recent Black academic philosophers none has been so committed to existentialism or phenomenological inquiry as has Lewis Gordon. Gordon appropriates Jean-Paul Sartre and Franz Fanon to a project of Black existentialism and phenomenological inquiry. His larger objective is to construct new foundations for the human sciences, in ways that forces them to affirm humanity; especially Black humanity. For him this involves a deep investigation of white consciousness and how it is manifested in bad faith. Bad faith is the denial of the existence and humanity of Black people and thus a constricted understanding of humanity itself. Existential social science and phenomenological inquiry is finally concerned with investigating bad faith. The struggle of humanity, moreover, is to achieve a new human consciousness and a new consciousness of what constitutes the human. This demands a revolutionary praxis. According to Gordon the Fanonian notion of revolutionary praxis involves each man in a constant struggle against degradation. Finally one might consider Gordon’s human science and existentialism as a form of radical, or indeed, revolutionary humanism. Gordon’s move concerns the global struggle to alter human consciousness.

Munford poses different issues and possibilities. His combination of historicism and structuralism suggest that social transformation, especially the liberation of Africans, will require a fundamental transformation of the foundations of the modern world. This involves an understanding of the a priori conditions of European civilization, its deep structure and the political and economic structures of the modern world. The revolutionary future, therefore, rests upon the uprooting of one civilization and its political and economic structures by another. Existentialism (especially in its radical construal by Sartre, Fanon and Gordon) and phenomenological inquiry yield important understandings of the world and human relationships; it is, however, limited as a philosophy of praxis and in its capacity to guide collective revolutionary behavior. Munford asserts that Gordon’s method is ahistorical and places whites as central to the revolutionary process.

Lewis Gordon’s Quest for a New Social Science

Gordon, in all fairness, is concerned first with the human condition, and the Black and white dialectic as it constructs a distorted, even perverted, humanity. The African is a condition for the existence of the white. Anti-black racism is the foundation of white supremacy. African consciousness and African revolutionary praxis is in effect a type of negation of negation in the Fanonian sense. In Sartrean terms the racial dialectic is rooted in the contradiction of Being and Nothingness or the discovery of a new humanism in displacing the old one-sided and perverted humanism. The revolutionary project is then to overcome both black and white in the interest of the human being as such. But it would seem that sociology is the sociology of the hegemon, hence of white consciousness. Gordon proposes an existential sociology that is able to encounter the objective or intersubjective and the existential, the individual. Moreover, the human condition is defined by metastability and dynamic chaos. This is the moment of man/woman before they are truly human and thus free.

By placing Gordon’s historiography alongside Munford’s it is possible to explore the revolutionary possibilities of each. Munford’s project is a radical one, rooted in political economy, historical materialism and structuralism. Munford seeks to provide through the philosophy and methodology of civilizational historicism a way to investigate global white supremacy and Black liberation. For Munford the critical dialectic is between white supremacy and Black liberation. Munford deploys structuralism in two ways. First to designate what is in effect the historical a priori, white supremacy, and secondly to pin point white supremacy as the generative mechanism of the modern world. To restate, the historical a priori is that set of conditions, what Munford designates civilization, which precede and determine the current historical epoch. The historical a priori is historically constituted, and congeals as that set of generative structures that are determinative of the present moment in history. This moment for Munford is defined as the epoch of global white supremacy. Its foundation is white civilization. In the West the decisive dialectic is between white supremacy and Black liberation. Blacks include Africans, Caribbean, Central and South Americans and European Blacks. Globally there is a dialectical contradiction between white supremacy and peoples of color generally. The maturing of this contradiction defines the revolutionary process itself and the future of humanity.

It is apparent that Munford’s work draws upon Marxism and at the same time supersedes it. Here it is useful to recall Oliver Cromwell Cox’s Caste, Class and Race. Munford’s work in some ways can be read as a discussion with Cox’s class-race dialectic, where class and class conflict determine race relationships. Michael Banton locates Cox’s work in the European class project and places it within the context of European epistemological concerns. It can be shown that what Cox wishes to explain is different from what Munford seeks to explain. They differ moreover, in how they identify the principal events in history. For Cox the explanation is class and class conflict; for Munford it is race and the conflict with global white supremacy. For Cox history is dialectically understood as the history of class conflict; for Munford modern history is the history of race conflict. At the same time Cox’s work has a genealogy in the Black Marxism of the 1920s and 30s, especially the works of Abram Harris, E. Franklin Frazier and Ralph Bunche. Munford reconfigures Marxism and structuralism to produce a new social science he designates civilizational historicism; social science that is ideologically partisan to the cause of Black liberation. At the same time it is part of an evolving Du Boisian project in Black social science.

Gordon configures social science as a science of the human being. He appropriates an existential reading of Marxism via Sartre and Fanon. Phenomenology is Gordon’s method of investigation. He wishes to study the human being in the current epoch; that is before she/he is fully human. Indeed, Gordon’s project is historical to the extent it is concerned with the historical a priori, which in Gordon’s case is the individual under conditions of limited possibilities, or in conditions of racial subordination and domination. Gordon’s ideological commitments are to human liberation i.e. humanity, which can occur as a consequence of the revolutionary transformation of the conditions of human existence. However, this process begins with the transformation of human consciousness. In the first instance this demands the undermining of bad faith as the principle condition of white consciousness. To the extent that Gordon’s project engages history it is as micro history, biography or the history of consciousness. This is Fanonian and Foucaultian at the same time.

Paget Henry: The Africana Subject and Africana Reason

Paget Henry’s works, especially his Caliban’s Reason: Introducing Afro-Caribbean Philosophy and a recent essay “Africana Phenomenology: Its Philosophical Implications” are important in their attempt to grapple with African and Afro-Caribbean postmodernism. Henry locates his project within the field of Africana Philosophy and as transgressive to European philosophical hegemony. Caliban’s Reason, i.e. the rationality of the Africa world, is subversive to western rationality. African phenomenology is the self reflexive activity of Africans, rooted in their own cultural realities. Henry rejects the continental rationalist stance, which elevates the rational subject above history and culture and turns to an Africana discursive practice, which embeds the rational subject in history and culture; in terms of Afro-Caribbean philosophy in Caribbean culture and colonial history. What Henry argues is that European Philosophy, which means for him European rationalism, is the thought of the colonizing subject; hence European philosophy is colonial philosophy. The disembodied subject, a la Descartes, is a fictive construction that serves to dissociate the philosopher from the crimes of his society. The Africana world, according to Henry, does not necessarily have this tradition of disembodiment, at least not in the colonial and anti-colonial moment.

On the other hand Henry insists upon the need for the mytho-poetic in the working up Africana, especially Afro-Caribbean knowledge and Africana thought. He insists upon adding to the historicist and radical thrust of Afro-Caribbean thought the sensibilities, thought and procedures of African religion and spiritualism. In this effort Henry privileges philosophy as central to social sciences of the African at the current stage. CLR James and Frantz Fanon failed to come to grips with African philosophy and spiritualism. Their project though radical did not fully grasp the Afro-Caribbean masses they sought to liberate. Henry seeks to add to the radical historicist the mytho-poetics of African art, philosophy and spiritualism.

It is at this point that I differ with Henry. In fact I am calling for the elevation of ideology as the central project to be developed within Africana thought. Philosophy, I am suggesting should be considered a sub field of ideology and historical phenomenology. This thrust fits the moment of war and empire and the need for a new anti-imperialist and anti-neo-colonialist struggle in Africa and the Caribbean and a new anti-war and social justice thrust in Afro-America. This move seems necessary in order to overcome the problem of essentializing African thought and constructing it as religion. Moreover, the problem of romanticizing African thought as primarily religious, idealist and spiritual, is challenged in the sense of contextualizing philosophy, religion and thought as part of ideology. At the same time we look towards discovering the materialist, agnostic and atheistic and skeptical trends within African thought. And to view these two trends as part of the class, social and ideological struggles within Africa. It asks, moreover, how this struggle of ideas, parties and movements has manifested themselves in contemporary African, Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American thought. Otherwise we deny that Africa too had classes. There was class conflict. There were ethnic and cultural struggles. Certainly the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade was contextualized within multiple struggles, including those within ethnic, national and cultural groups. And certainly, if not before (which I doubt) no doubt during and after the Trade Africans were segmented into classes.

At the most basic level there were the classes and social groups that joined European slavers in hunting, capturing and transporting Africans to the coast. There were states that emerged solely on the foundations of the slave trade, such as Dahomey. Then there was the example of the Akhan elite who sold the plebian and poor people of their own societies into slavery. Classes of traders, merchants etc were in conflict with the interest of the larger mass of Africans. This is an early form of class emergence and class conflict in West Africa, which inscribed itself onto the African landscape. These classes, even in the early stages of the slave trade, brought forth conflicting philosophies, attitudes to religion etc. However, these differences were contextualized as part of a larger ideological conflict, between the ideas, religions and beliefs of the African elite and ultimately slavers and the mass of African peasants, workers and the broad plebian mass. It is precisely this ideological struggle that I believe is the starting point for inquiry, rather than an uncritical and ahistorical embrace of religion as the sole form of African philosophy.

Hortense Spillers’ Geography of the (lm)Possible

Spillers’ asserts a distinct attitude to African being. Indeed it is the realm of the possible, perhaps even the infinitely possible, and the beyond possible, inherent to the psychic constitution of the individual African that concerns spillers. She makes what I consider a Husserlian move; she suspends judgment and permits the African to ‘speak ‘for herself. And to speak is to be, to exist. Her move is existential, yet it is a type of psyche/phenomenological move. Hence, the move is profoundly humanist and stripped of all a priori considerations and determinations such as cosmic or spiritual a prioris. Her phenomenology rejects the structuralist concern with determinations and allows the subject the freedom to exist. However, the African Being is polymorphous and infinitely possible and radically free.

Race and the Multiple Determinations of Polymorphous African Being

White civilization and European culture, insists Franz Fanon, have forced an existential deviation on the Negro. W.E.B Du Bois argues that from within the folds of this Fanonian existential deviation the Negro invents himself through resistance. Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction should be read as a study of how this resistance determined, or indeed, overdetermined, the geography of American history, where the dialectic is triangular at the level of political events (the North, the South and the Negro). The dialectic of race and white supremacy, of white oppression and Black liberation, is at its core. In both cases the issue is the epistemology of African Being. Du Bois sees African American Being as historically constituted in the vortex of resistance and race conflict and Fanon observes the psychological and identity problems created by white supremacy for Africans. Each is an instance of explaining African Being; each asserts an epistemology of Black Being. Munford draws on each, but uses methods of analysis associated with Du Bois’s historicism. What we end with is the understanding that African reality is complex, demanding complex theories and methods, requiring multiple angles of observation. African reality is the result of multiple determinations, some specific to the African world and African consciousness, others to global realities.

These determinations, however, rather than being static, are fluid and changing. There is a dynamic and complex interaction of forces, processes and events that determine African time and Being. What Munford does is to insist that through historical and political economic analysis, anchored in an ideological commitment to Black liberation a new movement for liberation is possible. Multiple determinativeness expresses the existence of multiple possibilities within the framework of dialectical complexity. Dialectical complexity assumes rather than a hierarchical situation of determinations, heterarchy or multiple determinations and causations. In a moment of acute and dynamic dialectical complexity (what Stephen Jay Gould calls punctuated equilibrium) the situation tends to instability and fluidity, yielding conditions for revolutionary ruptures within the global social system. In a review of Munford’s Race and Reparation I argued that his civilizational procedure predisposed analysis to a hierarchical, top down, modality and towards reliance upon single determinations. This cause-effect, linear or deductive nomological approach to explanation does not easily or readily grasp the complexity of socio-historical realities, their heterarchical or multideterminative nature in a situation of dialectical complexity and rapid movement and change in all levels of the global system. In many respects as the global system of white supremacy and capitalism has become interconnected and is intertwined with civilizational, economic and ideological events and processes in Asia, Africa and Latin America, and therefore become more complex, we are forced to adopt less deterministic modes of explaining this system. Rather than strict causalities, we are dealing more often with probabilities and far from equilibrium dynamics In a earlier review of Munford’s work I stated “Thus a profound revolutionary crisis, of the type Munford suggests, is necessary to undermine the global white supremacist system will involve a situation where, conceivably, civilizational events and levels conflict with political and ideological events; where economic events and civilizational events conflict. Here the moment is determined heterarchically, rather than hierarchically.”

Rather than single determinations, there are multiple determinations, where the movement of the system is determined not from its equilibrium state, or balance, but far from equilibrium; by what has been referred to as chaotic dynamics. On the other hand, Gordon’s phenomenological social science starting at the level of the individual seeks to advance to an understanding of African Being under conditions of ethical bad faith on the part of the vast majority of white folk. How, Gordon asks, to overcome this problem that threatens the existence of humanity itself. For him it is the praxes of raising consciousness on both sides of the color line.

A Proposal for the Future

Besides ideology, historical phenomenology is the other part of my alternative to Henry’s turn to idealism. Historical phenomenology is the project that I associate with Du Bois’ work. Historical phenomenology is a phenomenological movement, which understands the objects to be understood as historically constituted objects; however, constituted in and through the conscious action of human beings. Historical phenomenology in the Du Boisian construal is materialist, in that it looks not alone at the ideas and intentions of humans, but the determinations within which choices, beliefs, ideas etc occur. It is at this moment that I think we discover a convergence of Sartrean Existential Marxist phenomenology and Du Boisian historical phenomenology. While Du Bois’ historicism is best understood from his work Black Reconstruction in America, we glimpse his phenomenological work in The Souls of Black Folk. A reworking of these texts is the foundation of what I consider to be a Du Boisian historical phenomenology. Sartre’s phenomenology starts with Being and Nothingness, however, his historical phenomenology is witnessed in his Critique of Dialectical Reason, and his so called Existential Marxist work. Both Du Bois and Sartre propose a critical challenge and reworking of modern thought. Each proposes a move from philosophy to ideology. Each (Sartre most emphatically) leaves European thought and philosophy, claiming that a good part of it is only fit for the dustbin of history. In Sartre’s Critique it is ideology that informs philosophy. It is phenomenology that guides reflection. Both Sartre and Du Bois remain materialist, atheists and critical scientific thinkers. This is the radical positioning which I think Paget Henry is striving towards, but he is waylaid from because of his turn to idealism and religion.Lastly, Fanon’s engagement with the colonial mind and the multiple problems of identity and consciousness created by colonialism is the last part of the synthesis I am proposing. Fanon conceptualizes Europe and the European Mind as in crisis. It is the crisis of its science and of reason; a conclusion arrived at by Husserl in the 1930’s. This is a crisis of civilization for both Fanon and Husserl. However, Fanon, like Sartre and Du Bois, does not believe that this European civilizational crisis can be resolved within the confines of Europe or of European thought. Husserl believes it can be. Du Bois, Sartre and Fanon insist upon a revolutionary alternative to the crisis of Europe, but a revolutionary alternative which both changes the relationships between Europe and the non European worlds, but will alter in a revolutionary manner the internal dynamics within the Afro-Asiatic worlds. Africana thought by positioning itself thusly makes a move not to save Europe but to speed the moment when Europe qua Europe ceases to be an obstacle to humanity and development of humanity. But it makes a decisive move to resolve the world crisis, based on a trajectory of science, ideology and revolutionary engagement. This seems to fit the intent and scientific/phenomenological work of Sartre, Du Bois and Fanon.

Leave a comment