“If a man die, shall he live again? All the days of my appointed time will I wait, till my change come.”

Job 14:14

“Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.”

Rabindranath Tagore, Gitanjali 35

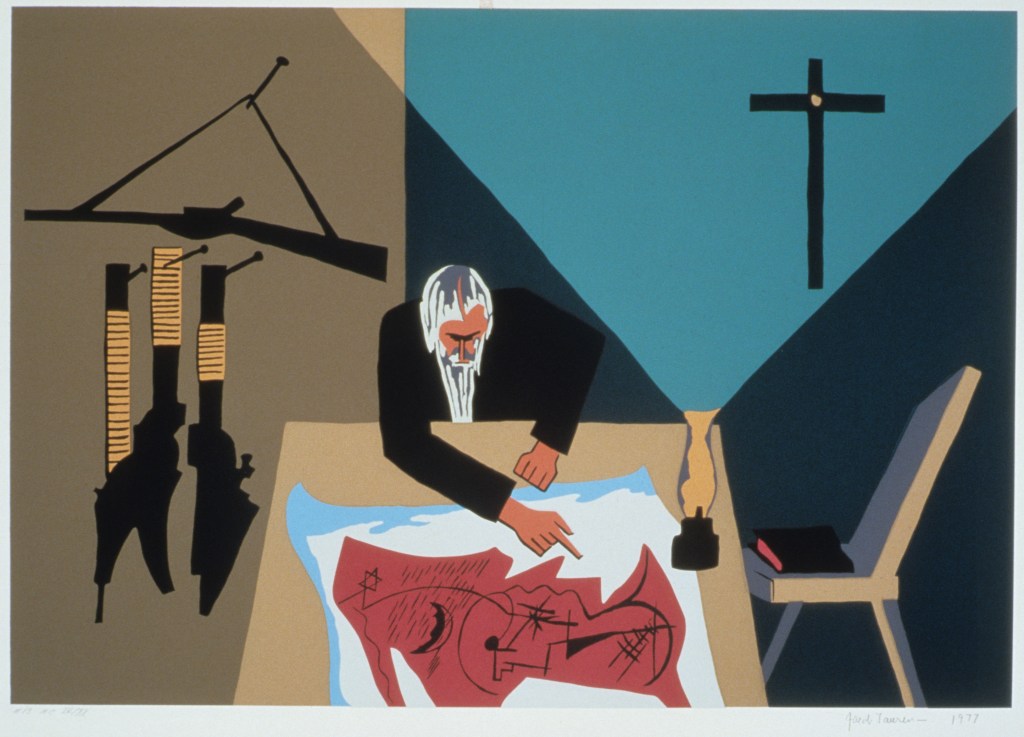

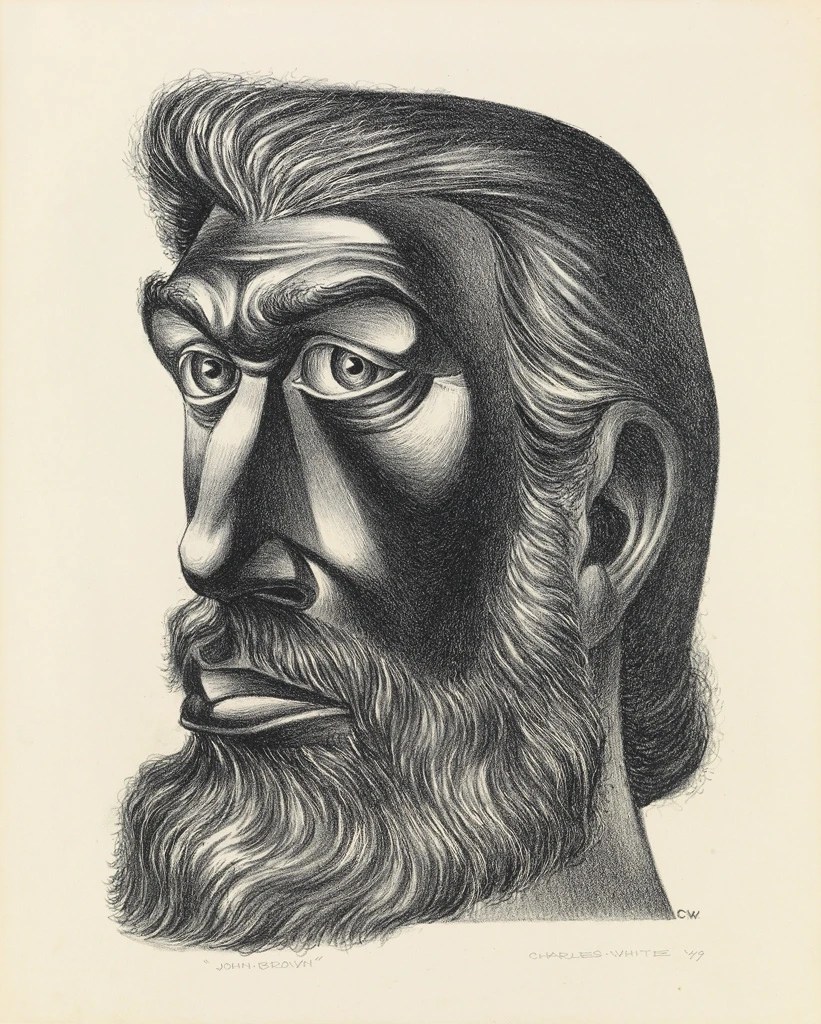

The martyr’s spirit widens after death. Given to a great cause, offered in sacrifice for a principle, their life spins out and upward, toward the infinite and into the living history of men’s consciousness. Such a man was John Brown. And yet as the years march on, the wide lesson of his life has been flattened. Some know the song, and can sing, “His soul goes marching on,” but of what quality was the soul, and what moved it? What was the height and depth and breadth of his life? What forged that spirit, so unyielding and yet so tender, so moved by the suffering of the enslaved that he would die to see them free? What could the soul of John Brown mean to the American people today, and especially to the masses of white poor? And could we, in our time of great confusion and moral crisis, see such a spirit live again?

Reclaiming A Revolutionary

John Brown is an enduring symbol of American history, and for good reason. He holds a special place of honor in the heart of Black folk. But we must be clear on the reason his life holds an eternal lesson, or risk losing a potent weapon for the people. For many today, Brown’s life is shortened to just the three days of his attack on the arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1859, and thus a two-dimensional John Brown is produced and reproduced.

He is claimed by elements of the white left and by those whose conception of revolution begins and ends with armed struggle and guerrilla warfare, who romanticize the gun and the individual act of violence. For them, John Brown is exemplar of the anarchist propaganda of the deed, a Luigi Mangione hoping to incite wider violence and popular revolt with a brave but doomed act. Brown is sometimes claimed by Marxist theorists and his life squashed into a limiting framework of pure class consciousness.

Brown today is also honored by liberals as simply a “historical” figure without any consideration for what history he occupied, remembered in name but stripped of substance. For example, “The Spirit of John Brown Freedom Award” is given each year by the John Brown Lives! nonprofit to a wide range of recipients of any cause considered progressive, from immigrant rights to environmental justice. Past awardees include Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine and Aaron Mair, president of The Sierra Club.

But Brown is much more than his fateful raid at Harpers Ferry. To understand him we must come to him through the striving of the Black proletariat for freedom — we must come to him through W.E.B. Du Bois. For it was the institution of slavery which sought to crush the humanity of the Black proletariat, and the Black proletariat’s struggle to break its shackles and seize freedom, which mortally wounded the conscience of John Brown and made clear to him the moral choice of his time and of his life.

It is John Brown’s moral choice to reject whiteness and struggle to defend the humanity of Black folk that, more than the shock of his attack on Harper’s Ferry, or even the attack itself, makes him a man for today. He saw the anti-slavery struggle as the struggle of his time which held in its great and terrible circumference all others. In the midst of a stifling white supremacist social system, and against all social laws of the day, Brown made a choice — and it is this capacity to make the moral choice which makes every ordinary human being an extraordinary force for change. The moral imperative is the revolutionary imperative, and the choice before us today, as it was for Brown then, is the moral choice.

John Brown found ambivalence to slavery, that great denial of Black humanity, too great a burden for his spirit to bear. Brown called the struggle against slavery “a cause which every citizen of this ‘glorious Republic’ is under equal obligation to do, and for the neglect of which he will be held accountable by God, — a cause in which every man, woman, and child of the entire human family has a deep and awful interest.”

It was because he knew and loved the enslaved that Brown could not stand idle. Du Bois writes, “Of all this development John Brown knew far more than most white men and it was on this great knowledge that his great faith was based. To most Americans the inner striving of the Negro was a veiled and an unknown tale: they had heard of Douglass, they knew of fugitive slaves, but of the living, organized, struggling group that made both these phenomena possible they had no conception. From his earliest interest in Negroes, John Brown sought to know individuals among them intimately and personally. He invited them to his home and he went to theirs. He talked to them, and listened to the history of their trials, advised them and took advice from them.”

Brown was confronted with slavery in his childhood. He was born, writes Du Bois in John Brown, “as the shudder of Hayti was running through all the Americas, and from his earliest boyhood he saw and felt the price of repression — the fearful cost that the western world was paying for slavery.”

Du Bois tells, “But in all these early years of the making of this man, one incident stands out as foretaste and prophecy — an incident of which we know only the indefinite outline, and yet one which unconsciously foretold to the boy the life deed of the man.” After driving cattle to the home of a landlord, Brown was invited in, and met an enslaved boy beaten and abused right in front of him by his host. Against this inhumanity Brown’s young soul chafed and he asked, troubled, “Is God their Father?”

“And what he asked,” writes Du Bois, “a million and a half black bondmen were asking throughout the land.”

As a child Brown learned the English Bible, its language and logic, but his religious upbringing was soft and sensitive, nourished more by wandering in the cathedral of the forest than in the pew on Sunday, and it was only later that the child’s simple but strong morality would become that of an iron Christian love. He calloused his hands with all kinds of physical work and with all kinds of people, “now a land-surveyor, now a tanner and now a lumber dealer; a postmaster, a wool-grower, a stock-raiser, a shepherd, and a farmer.” The cold hand of death entered his life early and often, teaching him as no school teacher could the brevity and sanctity of life, taking first a lamb, then his mother, his first wife, and nine of his children.

It was Brown who struck in Kansas bloody blows for a state free from slavery in a civil war before Civil War, who rode out at evening with deadly justice on his brow and rode back at daylight with widows behind. It was the steel of Brown’s principles that led him into financial battle with the might of the wool industry when, for a time, he was a prominent seller of farmers’ wool. And it was those same unrelenting principles that ruined him when powerful buyers colluded to lowball his fair-priced product and Brown refused to yield. Before injustice the personality of Brown, like a great oak, could never bend, and would not break.

But it was also Brown who “When any of the family were sick…sat up himself and was like a tender mother,” recounted his children. When one of his daughters was ill he stayed up all night nursing her with what medicine and comfort he had, and when she died he broke down and wept. This, too, was the personality of John Brown.

All this went to the making of a thinking, feeling man, not merely a derivative of economic laws or collusion of disinterested historical forces but a conscious, grasping soul, “ever looking here and there in the world to find his place. And that place, he came gradually to decide in his quiet firm way, was to be an important one.” James Baldwin in his essay “The Creative Process” considers the possibilities that existed for a new kind of freedom and a new relation between people in a young America. He writes, “But the price for this is a long look backward whence we came and an unflinching assessment of the record. For an artist, the record of that journey is most clearly revealed in the personalities of the people the journey produced.” And up against Brown’s questing personality, grating and scraping and bleeding, rose the evil of slavery and the moral crisis of white supremacy.

The Moral Choice: Reject Whiteness, Rejoin Humanity

So what is the spirit of John Brown for today? We know it must be a moral choice which rejects whiteness, which is a separation of yourself from humanity. To know the spirit of John Brown today, and the possibilities of the moral choice, we must know the souls of Black folk. We must ourselves be transformed by the Black freedom movement and by the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr.

Previous European movements and revolutions had made their focus the individual, his rights and ability to reason. King recognized in America a need for a transformation of the individual for the transformation of society, and for a “moral revolution of values.” To build a new society requires new human beings. This new human being is responsible not just to a class or nation but to all of humanity, and only the force of love is fierce and wide and strong enough to bind all of humanity to this new human being. What is the great power of this love? It is that no one can keep themselves separate from humanity, no one can accept the delusion of safety, no one can be white, who loves humanity. The great theorist and soldier of this revolutionary and transformative love was King.

In his sermon “Paul’s Letter to American Christians” King tells of the indispensability of love to the American struggle for freedom and democracy. “You may even give your body to be burned, and die the death of a martyr, and your spilled blood may be a symbol of honor for generations yet unborn, and thousands may praise you as one of history’s supreme heroes; but even so, if you have not love, your blood is spilled in vain…Without love, benevolence becomes egotism and martyrdom becomes spiritual pride. The greatest of all virtues is love.”

Here is a great lesson for the young people of today. While many forces in our society pressure youth to individualism and materialism, to be concerned only with your own comfort, career, and image, and sell us the lie that we can live separate from the suffering and pain of those around us, King challenges us to an alternative set of priorities and to new values. It is in commitment to the uplift of humanity that the individual finds their greatest freedom, and life its greatest meaning. This is a powerful message to the youth of today: that you need not act alone, and more than even what you do, it is the moral choice and the animating purpose behind the act that ultimately affects the greatest change in yourself and in the world. It is the evolving moral consciousness of people, and their decision to forego safety and act upon that all-humanity conscience, which more than any other force moves history forward.

We have as evidence of the transformative power of this revolutionary love and the moral choice to reject whiteness the lives of those in the Civil Rights movement. When King put out the call for people to come South and join the struggle for Black liberation, students and ministers and ordinary people of all kinds answered. They rejected the false safety whiteness promised them and cast their lot in with the striving of Black folk, joining picket lines, marches, voter registration drives, and lunch counter sit-ins.

We have as evidence people like Reverend James Reeb, a unitarian pastor who, moved by the TV footage he saw of police attacking marchers on “Bloody Sunday,” answered King’s call and flew South to join the marches from Selma to Montgomery. On March 9th, Reeb and two other ministers eating at an integrated restaurant were attacked and brutally beaten by white men with clubs. He died two days later. King eulogized Reeb, saying, “His crime was that he dared to live his faith; he placed himself alongside the disinherited black brethren of this community,” and “demonstrated the conscience of the nation.” He was one of those who “dares to love and rises to the majestic height of moral maturity.”

Or remember Viola Liuzzo who, watching the “Bloody Sunday” march on TV, joined a protest at Wayne State. Leaving her children with a friend, she called her husband and said this “was everybody’s fight” and drove to Selma, where she volunteered to transport marchers back and forth from Montgomery in her car. While driving she was overtaken by members of the Ku Klux Klan who, seeing her with a young Black man named Leroy Moton, shot and killed her. It is the long moral arc of the universe which solemnly bends to touch the grave of Liuzzo today and honors her courage.

Jonathan Daniels, a seminary student, answered the call in August 1965 and was arrested with 28 others for picketing the white-only stores in Fort Deposit, Alabama. After being denied parole and held in a jail without air-conditioning for six days, they were released, and Daniels along with a white Catholic priest and two young Black activists walked to a nearby store for a cold drink while waiting for transportation to arrive. At the door to the store they were stopped by white construction worker and deputy sheriff Tom Coleman, who aimed a shotgun at seventeen-year-old Ruby Sales. Daniels pushed Sales out of the way and was killed by the shotgun blast. Of Jonathan Daniels, King said, “The meaning of his life was so fulfilled in his death that few people in our time will know such fulfillment or meaning though they live to be a hundred.” Daniels himself wrote, “We go to preach good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord. We go to stand with the captives and the blind and the oppressed. We go in ‘active non-resistance,’ not to ‘confront’ but to love and to heal and to free.”

There has been written, if the people will take it up, a new covenant for the people of America in the struggle of the Black Freedom Movement. Under this new covenant and unmediated by whiteness, new human and national possibilities can be born. It is the spirit of King and the struggle of the Black Freedom Movement for freedom, peace, and democracy which transforms the moral choice for today and which makes possible a life worthy of humanity. To rejoin humanity is to take up a responsibility for humanity, to build, as King says, the World House and the Beloved Community, to be “caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” It is through the fiery heat of this love and the light in the eyes of this new human being which passes the soul of John Brown to us today.

The Price to Pay, the Life to Gain

We live in a great convulsion, when the world order established after World War II, of guaranteed American economic and intellectual hegemony, collapses with a titanic weight, and like the sudden shift and snap of a continental plate, precedes the release of enormous human energies. “Even armed with this morality of the club,” writes Du Bois, “and every advantage of modern culture, the white races have been unable to possess the earth.”

The white poor, promised safety and protection by the logic of whiteness, find themselves in a boneyard of former industry, their wages stagnating, infrastructure crumbling, school funding an afterthought to missile packages for endless wars, and their lot more and more in common with the Black poor.

Does Trump recognize this? Does the MAGA movement? There is a stirring in the consciousness of the people that propelled Trump to power, that tide of discontented, those anti-elite working people bone-weary of war, who have felt the hollowing of the nation’s industry as a starving man feels the hollowness of hunger.

But more than just an economic crisis, they find themselves confronted, like Brown, with a moral and civilizational crisis. The great tide of people, poor, many without an education, or often in spite of one, come groping, searching, begin to stretch out a hand, begin to ask of themselves and each other the questions that shake the foundations of history: What, if not this, will our country be? What principles are we to live by? What ideas will be my guide now that the university, the government, even the church, the institutions I once trusted, have proven themselves inadequate to the task of a human life? What does freedom mean, and how will it be achieved? There is undoubtedly a deep disdain for the rotting status quo of liberal vanity, and a desire for a truer democracy, but there is not yet a conception of its cost, or of the path forward.

“The cost of liberty is less than the price of repression,” writes Du Bois again and again in John Brown. Now the cost of slavery has become the cost of empire, and Americans today are finding that the cost of empire is too great. What does white modernity offer? Did John Brown find a resolution to that crisis in his time? He found it offered spiritual death, and he rejected it, electing to be hanged instead, but elevated in death to a more perfect freedom: the freedom to labor in love for humanity and especially the oppressed.

As long as we have the courage to make the moral choice, to reject whiteness and rejoin humanity, the spirit of Brown will be there. In the struggle for a new society and a new civilization, which follows the torch of darker humanity after the great death throes of white modernity have rolled away, we will need new human beings. It is the great capacity and test of each of us to choose our allegiance, as Brown chose, and I think it is no exaggeration to say that this choice is between life and death. I do not know each stumble and leap that marks the path ahead, but I know the way forward must be navigated by the moral choice, and that the struggle of Black folk for freedom is our inheritance for the future.

After the raid on Harpers Ferry failed, John Brown was captured and brought to trial by the United States government. The verdict was guilty, the sentence death. In prison, Brown turned to his journal.

“I can trust God with both the time and the manner of my death, believing, as I now do, that for me at this time to seal my testimony for God and humanity with my blood will do vastly more toward advancing the cause I have earnestly endeavored to promote, than all I have done in my life before.”

“My love to all who love their neighbors. I have asked to be spared from having any weak or hypocritical prayers made over me when I am publicly murdered, and that my only religious attendants be poor little dirty, ragged, bare-headed, and barefooted slave boys and girls, led by some gray-headed slave mother. Farewell! Farewell!”

So died John Brown.

“This was the man,” writes Du Bois. “His family is the world.”

So there is still, for each of us, a price to pay. And that price, though not blood or the gallows, may yet be our life. But to lose the unlife of whiteness and gain the life of moral responsibility to humanity, and struggle with those in chains? What a prize!

For what life does whiteness offer? It is no life at all, but a shadow of one, a pale imitation, cut off from the great flow of Life. For John Brown, to lay that burden down meant to take a greater one up, a task that might require your life as collateral, but which frees your soul. That price is the death of the old self which clung to the impossibility of safety, to that delusion of separateness, to sterility and still water, to eternal sick-sweet boyhood. And then after, striving upward and outward, comes a rebirth — into complexity, to maturity, to reality, into the Beloved Community: to humanity.

It is the only choice, and it is not a choice anyone can make for anyone else. But you’re not alone, for the world makes this choice every day, every hour, again and again, with you. We have, urgently and fiercely, a great responsibility to make it, and despite the lies we’ve been told and the bribes we’ve been offered, we do have the strength to make it, if we will.

Leave a comment