According to recent polls 70 percent of Americans say the country’s political and economic systems should be fundamentally reformed; 15 percent say they should be torn down and replaced with something new. In history such rejections of the political and economic systems are a sign of a pre-revolutionary or civil war situation. They are a memento mori, a reminder of the death of a system.

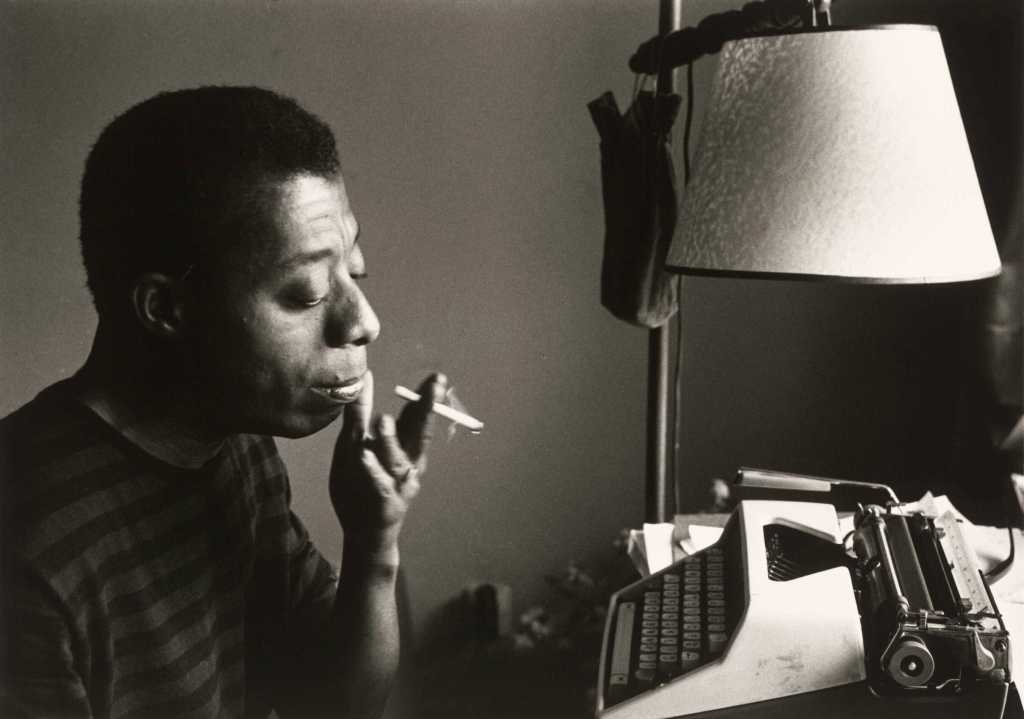

W.E.B. Du Bois and James Baldwin give us intellectual tools to explain this moment. Their combined bodies of work are massive and are, by many measures, the most significant body of revolutionary thought produced in the United States. They are two of the most important thinkers of the modern epoch. Both are thinkers for this time because they provide theoretical and ideological foundations for new and better theory and foundations in the battle of ideas. Both creatively reground thought and theory, presenting alternatives to the civilizational, philosophical, and ideological foundations of Western thought. In the end, their vast bodies of work constitute a revolutionary and epistemic break with liberal and bourgeois assumptions which define the West’s worldview. They sought to understand the U.S. social system, what I call the White Supremacist Social System. Deploying different methods for knowing, they produced creative and scientific ways to explain Black folk and what Du Bois called the Black Proletariat. They examined Black folk’s moral, social, and revolutionary capacity. Baldwin’s oeuvre explains Black resistance in the face of white supremacy and whiteness. Baldwin, as much as any American writer, closely examined white Americans and how whiteness and white identity trapped them in delusions about themselves and America.

Each combined revolutionary thinking with commitments to solidarity with the world’s peoples. Du Bois is the father of modern sociology and radical U.S. historiography. He is also the father of modern Pan Africanism and the Civil Rights Movement. He stood with the Afro-Asiatic revolutionary movements and the world peace movement, was a socialist most of his life, and near its end joined the Communist Party of the United States, declaring “I believe in communism.” Baldwin similarly was a socialist, a fighter for peace, and a partisan of Pan Africanism and the Afro-Asiatic revolutionary movements. Neither abandoned the struggle of the poor. This essay attempts to explain how Du Bois and Baldwin produced a body of thinking which is the basis for a scientific understanding of the U.S. social system, its current crises, and paths to revolutionary change.

W.E.B. Du Bois: A Revolution in Social Science

Out of the chaos of the social sciences of the early 20th century, Du Bois sought to create science which could explain racial oppression and colonialism; what he viewed as the principal contradiction of liberal democracy and the capitalist organization of society. His book The Souls of Black Folk announces a new approach to social science, where he transgresses the West’s assumption that Black people were not human; Black people were human, he insisted, and could be studied scientifically. The assumption of early white sociology was that because Black folk were less than fully human, they should be studied using biology, but not social science. Du Bois thought that social science might be deployed to solve the crisis of U.S. democracy and transform society, producing a multi-racial democracy.

He boldly proclaimed, furthermore, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line”; asserting the crisis of modernity, democracy, social science, and knowledge itself was racial oppression and colonialism. The crises of American democracy he traces to slavery and the defeat of Reconstruction. Moreover, while slavery ended, Black folk were not free.

To scientifically study race in the modern world Du Bois demonstrated that a new way of knowing society was needed and that the civilizational assumptions of white social science, especially as regards race and Black people, had to be rejected. Social and human science, he believed, must engage complexity; hence rejecting the simplistic reductionism and mechanics of white and positivistic social science.

An Epistemic and Civilizational Rupture

Beginning with his empirical studies of Black folk and race, found in, for example, The Philadelphia Negro (1899) and The Souls of Black Folk (1903) leading to Black Reconstruction in America (1935) and The World and Africa (1947), Du Bois proceeded to radically rethink the human and social geographies and social sciences. This led him to new ways of engaging the global systems of race, class exploitation, national and gender domination and oppression. He was led to rearticulate precisely what class struggle (the central logic of Marxism) meant and looked like under conditions of the U.S. racialized social relations. His rethinking emerged from the African lived world and equally from what he early on saw as the crisis of European democracy and hegemony. The color line, slavery, and colonialism were the foundations of Europe and its hegemony, but they were also signifiers of its crisis.

However, his work evidences a civilizational rupture; first defining Black folk as human, but more, defining them as Africans and Africans in America. In a review of his Souls of Black Folk, he said that he wrote it as an African. In the essay “The Conservation of Races” he locates Black folk as Africans and part of a civilization rooted in Africa. In Black Reconstruction he asserts that the enslaved were “everything African.” In Dusk of Dawn, he asserts that African civilization was foundational to African Americans’ culture. His studies of the Black church point to its African cultural foundations in its modes of organization, governance, and administration. Black religious practices evidence African origins. The music of Black folk originates in African melodies, transformed through the trans-Atlantic slave trade to Sorrow Songs; a rhythmic narrative of a disappointed people, he said.

What he began and then carried out for the rest of his life, was a decisive break with the European view of humanity. Du Bois invents a new way of scientifically studying Africans and ultimately humanity. He makes a decisive break with the idea that knowledge is essentially a European thing, and that European knowledge was universal. He insists that the study of history and modernity from a European standpoint narrows the lenses of knowing and ultimately distorts knowledge. What comes out of European philosophy and human studies was Eurocentric and prejudiced in favor of humanity’s minority, white folk. In his Autobiography he says that while at Harvard and the University of Berlin, “I began to conceive the world as a continuing growth rather than a finished product.” And he speaks of the social sciences of that time as engaged in “fruitless word twisting.” As he faced “the facts of my own social situation and racial world, I determined to put science into sociology through a study of the conditions and problems of my own group.” Of the white world, he says in Dusk of Dawn that it was “thinking wrong about race, because it did not know.” It did not have either the philosophical or civilizational prerequisites to know. And what they didn’t know about race and democracy, they thought wasn’t consequential, at any rate. Du Bois passionately disagreed; what the white world didn’t know about race would turn out to be the most consequential thing about American capitalism and modernity.

Discovering the Black Proletariat: A Revolution in Knowledge

One of the great discoveries of revolutionary thought is of the Black Proletariat. This historically constituted and revolutionary category builds upon, yet supersedes, the Marxian notion of the class struggle. Du Bois saw the Black Proletariat as the central revolutionary force in the anti-slavery struggle. He saw it under slavery as an enslaved proletariat. The logic of this discovery leads to Du Bois’s proposing a historical logic that proceeds in threes: the Black worker, the white worker, and the white capitalist. Rather than a dialectic, as in a logic of twos, Du Bois proposes a trialectic, a logic of threes. He makes robust claims concerning the role of the Black Proletariat, including the possibility during the Reconstruction era of a dictatorship of the Black Proletariat being established in several states of the U.S. South. This dictatorship was a necessity, he reasoned, to secure a revolutionary democracy and the freedom of the former slaves.

The larger point is that the Black Proletariat is the central force in the revolutionary and democratic struggles of the United States up until now. It represents the highest levels of democratic, anti-white supremacist, and working-class consciousness. It is from a logical standpoint the working class in its becoming, which means that the Black Proletariat is the ground upon which the entire working class rises or falls. To achieve a revolutionary democratic consciousness, white people must reject whiteness; the working class must become more or less the Black Proletariat; hence the Black Proletariat is the entire working class in its becoming: a class for humanity. This expresses the revolutionary potential of the working class. This means the white worker, over time, becomes one with the Black worker; white workers start to think like and identify with Black workers. This is precisely the point that Baldwin makes; the first step to a revolutionary consciousness is for whiteness as an identity to be rejected.

James Baldwin, an Ever-Present Revolutionary Alternative

Baldwin remains the ever-present revolutionary alternative to a white world obsessed with itself and holding on to power. He viewed humanity as the focus of his intellectual and political efforts. He starts with humanity, and from that locus moves to study race and white supremacy as not only an American problem, but a human one. This gives to his writing and thinking an originality. He uncovered the workings and the machinery of racism and its predatory and pedestrian day-to-day practices and assumptions. He rigorously demonstrated how modernity engages complexity and difference through the lenses of race and white supremacy. He gave us the concepts and language to talk about and begin understanding the oppressive system of white supremacy in holistic ways. He probed its forms, its depths, its psychological and social psychological dimensions, its conscious and unconscious workings, its human devastation for Americans.

Baldwin showed that the dialectics of racism conditioned the dialectics of the social order. Economic exploitation and inequality function within the boundaries it sets, not the opposite. White supremacy was, he taught us, far more than ideology and more than a derivative of the economic system, but a system itself. He inverted the European Enlightenment and scientific orthodoxy’s agreed-to assumptions and logics concerning white folk, and even what sociological reasoning asserted about race. Race was neither natural nor normal. Whiteness was an abnormal and pathological (in both psychological and societal meanings) reality, birthed by the needs of the slave trade, slavery, capitalism, and European empires. Brought into the world by slavery, capitalism, empire, and their existential necessities, white supremacy takes them over and subtly and progressively, they become it.

Language, Art, and a Biography of Humanity

His oeuvre is a type of multi-volume biography of Black folk and humanity in the time of white supremacy. It can be thought of as a form of humanity’s self-narrative, told by one of its living, striving parts. The narrative is about more than Black folk, they are the concrete forms he gives to the human, but it is about the complexities, tragedies, comedies, strivings, pathologies, and failures that humans experience as they attempt to be human, while ironically trying to hold on to non-human (perhaps pre-human) and semi-human culturally invented identities and practices. It is this conundrum; the individual confronting the past, but realizing he/she must choose what side of the future they stand upon. This is the essence of most moral choices.

It is useful in understanding Baldwin as a biographer of the human to begin from an unusual angle: the language of the oppressed. In an essay entitled “On Language, Race and the Black Writer,” Baldwin says, “And for a black writer in this country to be born into the English language is to realize that the assumptions on which the English language operates are his enemy.” This is so because white English as language assumes this is a white nation, where the logic of this assumption is that Black folk must be either erased as a linguistic and cultural force, or physically eliminated. In the essay “Down at the Cross,” Baldwin observes, “For the horrors of the American Negro’s life there has been almost no language.” And what does not exist in language has no way of attaining public acknowledgement of its existence. In this very real sense, American society has not and till this day does not recognize the realities of Black life. This in many ways explains the emergence of a Black Social System; a system of language, beliefs, institutions, habits, and ways of life, which has little to do with the standards by which white people live. This system, among other things, validates Black people’s sense of their situation, which is ignored by the white world.

What Baldwin calls Black English is a language of resistance and it functions as such for Black folk. Baldwin, in his examinations of Black language, starts not with grammar, vocabulary, and syntax, but the role and functions of all languages. Language functions as the way of social communication, but significantly as narrating a people’s existence. Black English does precisely that. It came into existence out of brutal necessity. Black English functions like every language, to assert the humanity of the group which speaks it and to prevent that group being erased from history. It establishes that the said group is prepared to and does resist the oppressors and their language. Black English, therefore, is the preeminent language of resistance in America. It expresses a worldview, a people’s narrative, and gives rise to literature and music. Without it, he thought, there would be but one language, the English of white supremacy and whiteness.

Black English is hence the democratic alternative to white English and its assumptions. Baldwin concludes, “And after all, finally, in a country with standards so untrustworthy, a country that makes heroes of so many criminal mediocrities, a country unable to face why so many of the nonwhite are in prison, or on the needle (on heroine, or other drugs — A.M.), or standing, futureless, in the streets—it may very well be that both the child, and his elder, have concluded that they have nothing whatever to learn from the people of a country that has managed to learn so little.”

In its wider sense Black English is the language of the Black Proletariat; it is, therefore, the language of the most revolutionary democratic force in the nation. All that emerges from the assumptions of Black English serves the interests of revolutionary resistance. It is a language of the future; it is thus generative and futuristic.

The White Supremacist Social System and the White Civilizational Disposition

Baldwin and Du Bois assumed the U.S. social system was not as described by liberal and radical theory. Baldwin and Du Bois, rather, saw it as what can be defined as a white supremacist social system. The most foundational relationships in U.S. society are, therefore, race relationships. These relationships are determinative of class, gender, ethnic, and other social relationships. Yet most consequentially, power at all levels of society is determined by white supremacy. It is the overarching system; it is the unifying system in American society; without it, capitalist society falls apart.

The white supremacist social system emerges after the defeat of Reconstruction (1877) and its democratic possibilities. It consolidated a new racial order, which undergirded the new capitalist order. Its legal justification is the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896, establishing whiteness as constitutionally protected; thus, making Black rights expendable and secondary to the protection of whiteness and white privilege. The habits and social norms that proceed from this are the ground of the modern U.S. social system. Establishing whiteness as constitutionally protected meant that whiteness is protected by the state and its major institutions. The state is not only a defender of white supremacy but is itself white supremacist. The standards through which the economy, law, religion, education, language, art, literature, and music, among other things, operate are within the framework of the overall white supremacist system. In important ways the social system that arose upon the heels of the defeat of Reconstruction and the Plessy decision modernized white supremacy and white civilization, in the era of imperialism, war, and economic crises. It is being further modernized as the Democratic Party assumes the mantle of the vanguard of the defense of the white supremacist social system, as it both “condemns” white supremacy and claims to be the party of Black freedom and inheritors of the legacy of its leaders. The white supremacist system says to white people that in return for the state’s protection of whiteness, white folk are obligated to defend whiteness in their “self-defense”; this is called democracy.

The book The New Jim Crow, which analyzes the imprisonment of Black men, shows evidence that the Black Proletariat is the main target of white supremacy, and that the legal system is an arm of the white supremacist social system. American Apartheid studies housing segregation and discrimination; it shows extreme segregation among Black folk; separating them from jobs, health care, educational opportunities, and equal housing. Other metrics of social status, such as health and education, show Black folk less healthy and less educated than most Americans. However, the enduring status of Black folk, in fact over 20 generations, points to the existence of this overarching and determinative white supremacist social system. But the evidence regarding Black folk is indicative of what the social system is. What is shown is that the most significant way to understand American society is to understand it in white supremacist systemic terms.

Du Bois’s and Baldwin’s bodies of work detail in all its dimensions a social system that produces Black oppression. They both studied the capacity of Black people for transformative action to change this system. For both, therefore, the Black struggle was a struggle for freedom and to topple this social system.

What we learn from their work is that theories of revolutionary and democratic change must begin with understanding the white supremacist social system. The revolutionary, democratic, and emancipatory struggles must commit to the undoing of this system as the principal revolutionary task. And thus, this task highlights the centrality of Black freedom to democracy, as Baldwin insisted it is through this door (Black freedom) that all democratic and revolutionary forces must go.

The Black Social System

Black folk have created an alternative to the white supremacist social system, a system of resistance; a Black Social System. Baldwin and Du Bois devoted tremendous intellectual effort to explaining this system; this world within a world, or this nation within a nation, to use Du Bois’s language. It encompasses all the institutions of Black life, from churches, other religious institutions, art and music, literature, colleges and universities, families and extended social networks, fraternal and sorority organizations, community organizations of varied types, political parties, cultural institutions, and more. This complex set of Black institutions, networks, and organizations makes up Black life. All of this is the social form of Black resistance and resilience; Black existence, in many ways, exists within the Black social system. All of this gives a distinct, and in fact, very apparent difference to Black folk. Du Bois and Baldwin write and think from within the Black social system; from within the Veil, to use Du Bois’s language.

Counter-Revolution and Revolution: Now is the Time

Du Bois’s and Baldwin’s thinking, as I’ve sought to show, are complementary and produce the groundwork for theorizing capable of explaining our current political and ideological crises, and possible paths forward. Wars are occurring in many parts of the world. The U.S. empire is in decline, poverty increases, and for the majority of U.S. people, life is a dark and tragic landscape. Having recentered revolutionary theory, Du Bois and Baldwin offer theory which ascends to the concrete realities of the U.S. and the specificities of this nation, especially at this moment of crisis. Accounting for this, the trajectory which they envisioned was a revolutionary democratic struggle; a struggle that, as Baldwin put it, seeks to achieve our country and make America the last white nation. This means that all struggles for peace, democracy, and progress must be connected to dismantling the white supremacist social system as the obligatory struggle to achieve conditions for advancing the people and nation to the next stage of struggle which leads to a completely new social, political, and economic system. In the throes of these struggles, Du Bois and Baldwin viewed the Black Proletariat as the key revolutionary force. United fronts for revolutionary democracy and emancipation must be built upon this recognition.

In the last part of his life, Baldwin said many times the white man’s party was over; world humanity had moved beyond the West. He also asked, What would be the price of the ticket to create a new world? This question remains. The American people, in unity with world humanity, must ultimately answer this question.

In The Year of James Baldwin: God’s Revolutionary Voice, the Saturday Free School has gained experience and knowledge about people’s thinking. We have discovered that Baldwin captures their thinking and strivings; he provides ideas and language to concretely guide their action. We are on the cusp of major struggles for a new democracy and world peace; the people can decide the outcome and the future. We are, moreover, in a time when, as Martin Luther King Jr. and Baldwin taught us, the moral imperative is the revolutionary imperative.

The poor and working people are no longer satisfied to sit back and wait upon ruling elites. So much depends on the ideological and moral clarity of the people. The Year of Baldwin is a contribution to that clarity.

Leave a comment