When the students at the University of Pennsylvania suddenly broke off from the crowd and ran towards the lawn of College Green, jumping onto the roped off area of thin sprouting grass, the dam burst and something snapped. What had been simply the latest in an unvarying sequence of protests, marches, and rallies abruptly transformed.

In those first moments, a rush of people followed to flood onto the grass: for every student who set up a tent, twenty more coursed to stand around them, forming a large ring around the perimeter. Most of us were strangers, unacquainted, but we instinctively locked arms and elbows, standing straight and solid to protect the encampment from police and counter-protestors. We held on tightly to each other: some students faced outwards determinedly, while others faced inwards, watching the tents go up.

Students setting up the Gaza Solidarity Encampment at the University of Pennsylvania on April 25, 2024. The encampment, like the 100+ others across the United States, demanded universities’ divestment from corporations profiting off of Israel’s war and occupation, disclosure of financial holdings, and the defense of Palestinian students and culture. Penn’s encampment lasted sixteen days before it was swept at dawn on May 10 by Penn and Philadelphia Police. Photos by Joe Piette (LEFT, RIGHT).

The students’ faces were shockingly open and earnest. Looking at them, they felt both familiar and unfamiliar: some undergraduates and graduate students I recognized from classes, teaching—and yet they were imbued with a new character, which was suddenly beautiful. Rather than the usual inscrutable wariness or the sense of something hiding—or being hidden, left protected—behind the outward appearance, everything was out. Conviction—fear and awareness of risk—courage despite—and above all, faith, made serious and dignified.

Penn’s campus is always lively, and yet despite being so filled with activity, so often the university can feel superficial and cold. Something remains closed off: certainly to onlookers without, but also for those within, who ought to and must belong. We walk briskly, coming and going, caught up in aggrandized expectations and grinding away at ourselves in the pursuit of success. We become depersonalized: the inner human being becomes suspended, dubious, and the spirit becomes subdued and dejected.

The encampments ruptured this hard, indifferent veneer of the elite university. Ultimately, it was brittle and weak, readily giving way for a new human quality to be brought forward into the open. For hours we stood together, present, sharing our hopes and coming to know each other on this new, dedicated ground. People walked by, took photos of the spectacle, occasionally jeered and prowled, but often expressed their support, relief, and even gratitude. As people left for dinner or evening classes or as the light faded, others took their place, ensuring the circle continued unbroken.

Something was cracking in us. Unbeknownst to the comfortable, who hoped the tension would not break and their power could hold, the students moved. Their consciousness stirred; they joined together quickly and quietly. Columbia was no anomaly. It embodied a new spirit of defiance, confidence, and courage which swept the country.

The student protests were able to reestablish a moral center desperately needed in American society. By recovering a sense of humanity from the ruling paradigm of extreme, isolating individualism—and placing it back in its place as the guiding star—the encampments cracked open a path back to reality, creating openness to change and unleashing a deep but untapped capacity for moral clarity, courage, and struggle.

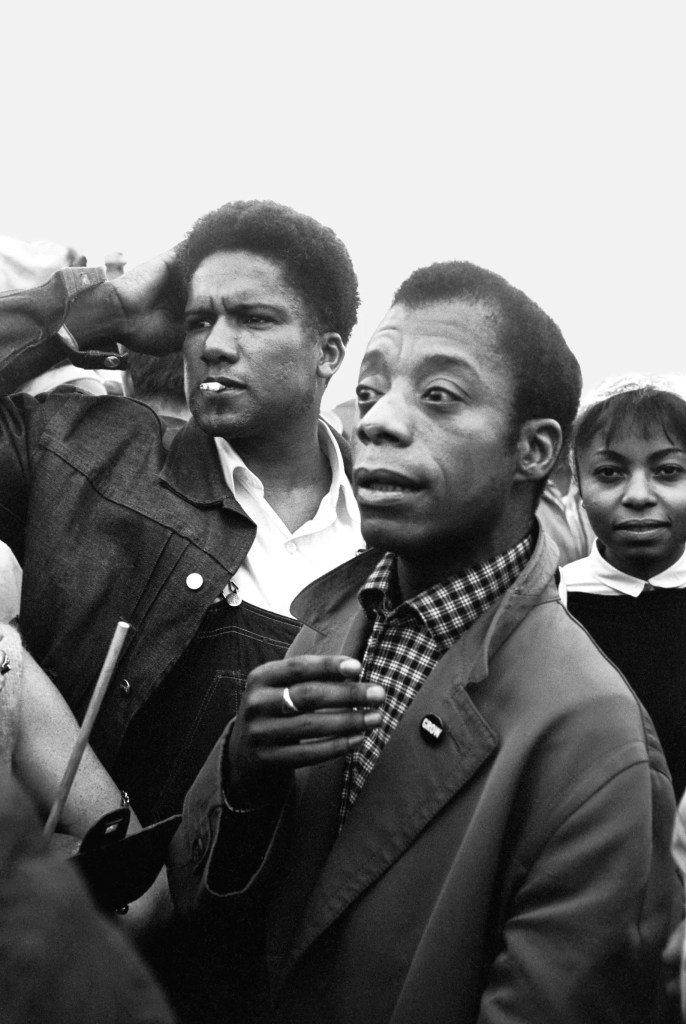

Left: The Refaat Alareer Memorial Library at the Gaza Solidarity Encampment. Alareer was a Palestinian writer, poet, and professor from Gaza, who had been slated to speak at the Palestine Writes Festival held at Penn in September 2023. An Israeli airstrike killed Alareer, who wrote the poem “If I Must Die,” in December 2023. Photo by James Ray. Right: James Baldwin on the march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. Photo by Steve Schapiro, from The New Yorker.

What initially felt like such a breakthrough, however, was crushed and disappointed. Universities refused to divest or disclose, with utter contempt for democratic governance and popular will. If anything, their desperation made them draconian, punishing the students so the genocide could continue more smoothly. The campuses today feel repressive and actively hostile, locked and barricaded against any expression of dissent or even of mourning. Things are constantly tense, with deep distrust across the moral lines which have been drawn. Any facade of normality is built on delusion or denial. For men, women, and children are still being murdered daily; starved, bombed, trapped in the rubble, and engulfed in flames.

And yet, such deep-lying human qualities—morality, vitality, resolve—are our greatest strength in political struggle, and remain so despite setbacks or unachieved objectives. The student encampments of the spring are a key to understanding the price we must pay—to salvage any possible future for Americans in this world that we have created. Even now, unanswered questions linger and nobody can yet see the end in sight: Where did it take us and leave us? How do we confront our shattered dream to complete what was started with such conviction?

I want to assess the student movement through the revolutionary and prophetic essayist James Baldwin, who best illuminates where this energy can go. In No Name in the Street, he writes:

“Power, then, which can have no morality in itself, is yet dependent on human energy, on the wills and desires of human beings. When power translates itself into tyranny, it means that the principles on which that power depended, and which were its justification, are bankrupt… But for power truly to feel itself menaced, it must somehow sense itself in the presence of another power—or, more accurately, an energy—which it has not known how to define and therefore does not really know how to control.”

The Moral Choice and the Revolutionary Imperative

The American student movement—and the students themselves—now faces great obstacles and challenges. But if the students accept the moral imperative of this time, they will find the revolutionary imperative again. In an age of “complicated” issues that relishes a utilitarian calculus of moral grayness, reviving morality as a real and open question—to force an actual encounter with the living soul, without deferring to any external authority—is a powerful act. It compels you to make decisions as a man or woman, as a human being: limited in the power to enforce your personal will, yes, but still having the necessary responsibility to internally grapple, to choose, and finally, to fight your battles.

The moral imperative means that before asking, Is it too hard? or Is it too radical? or Is the price too high? we ask ourselves, Is it right? And what is right cannot be too radical or too difficult or too personally costly, reshaping the limits of what we consider possible and expanding our capacities. During the encampments, this moral capacity was allowed to live and breathe within daily life as the foundation for social and political change. In risking ourselves and struggling for freedom, we grew closer to achieving our own moral authority.

Our moral standards were raised by the example of a truer, tested morality from a people halfway around the globe. Baldwin described the realization of the oppressed: “They do not know the precise shape of the future, but they know that the future belongs to them. They realize this paradoxically—by the failure of the moral energy of their oppressors and begin, almost instinctively, to forge a new morality, to create the principles on which a new world will be built.” The Palestinian freedom struggle embodies this new moral energy. Abubaker Abed, a reporter in Gaza, writes, “Our lives were stolen, but our souls remain beautiful. We smile when we see someone, somewhere, anywhere, raise the flag of Palestine in a street or in a football stadium, or a mother putting keffiyehs around her children’s necks and people talking about us as if they are part of us… This is the reality the entire world needs to know.”

Palestinian children raise signs thanking American students protesting in solidarity on their campuses, during a rally in Deir el-Balah in the central Gaza Strip on May 1, 2024. Photo by AFP. Friday prayers in Rafah on March 1, 2024, next to the ruins of a mosque destroyed by Israeli airstrikes. Photo by Ismael Mohamad, United Press International.

Morality is made concrete by the exemplar of those who love their children, their people, and the land too much to give up on struggle. The Gazan infant and child in the camp, the shaheed covered in dust and ash, the mother on the road and in the market, the father grieving, holding his family, the rare elders whose dignity and authority cannot be shaken, and those who still pray amidst the ruins of their churches and mosques: these are a people who have reached an advanced stage in their social relations. And the Palestinian people, in their martyrdom and unyielding, steadfast belief, reflect something back to us—the requirement of faith in our own humanity, linked to theirs.

While the genocide has exposed the bankruptcy of Western “values” once and for all, the Palestinian people are a testament to the fact that morality is a real force, with power to match and even prevail over any material disadvantage. After 70 years of occupation and over a year of intended death by fire, shrapnel, starvation, and disease, the people of Gaza have not bowed or bent; their souls remain beautiful. Despite Israel’s assumptions and hoped-for plans of destruction, the Palestinian people refuse to turn on each other. Each citizen of Gaza who refuses to be cowed, who is forced to accept death but refuses to die for nothing, is neither a terrorist nor an object victim for charity, but a human being with a backbone who has achieved a consciousness that bends the material world around them. Such human consciousness is the defining force of history.

Moral consciousness broadens the possibilities of political capacity. The individual transcends their singular limitations and joins a beloved community; the more one is willing to bear and to sacrifice, the deeper the scope and the wider the horizons of human action. In coming into one’s full agency, one navigates great complexity to defy both expectation and probability. The fight for freedom, whether in Palestine or America, furnishes a moral center, a creative optimism, and a sense of the human being that endures and also opens up the future.

The encampments manifested and defined that yearning for a moral center. In this American society which is so cold and distrusting, the encampments brought into being the crucial sense of community, buttressed by freedom from fear—or a need for freedom greater than fear. The stakes of life or death overshadowed the desire for privilege and safety, illuminating a new energy and conviction to truly live.

These students are the descendants of the Civil Rights Movement, though they may not know it. In substance, they bear the most potential resemblance to the young Black and white Freedom Riders who went South and participated in the Freedom Summer. As they seek their political maturity and the key to their own identity, they have experimented with and tried on the various mantles of the legacies that have been offered them—the New Left, the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power, the anti-apartheid movement, the Occupy movement, and Black Lives Matter, to name a few. But when put to the test across the country, it is the Black Freedom Tradition that the students instinctively turn to as their greatest inheritance, singing songs like “We Shall Not Be Moved” and holding onto each other for spiritual strength.

Such moral and political consciousness is a revolutionary consciousness, through which a new sense of self and a new identity can be achieved. In choosing to live by the moral standards proven by the people of Palestine—what their experience tells us about life—we rediscover the standards and principles of our own revolutionary inheritance.

The Birmingham campaign began with a boycott, but then trained high school, college, and elementary students in nonviolence. Students planned to walk from the 16th Street Baptist Church (pictured, right) and other churches to City Hall to speak to the mayor about segregation. More than six hundred students were arrested, with jails reaching their capacity. Birmingham Al, 1963. Photos by Bob Adelman (LEFT, RIGHT).

Students, Movements Past, and the University Today

The students are being tested by the same moral choice laid before the American people generations ago, which is a choice larger than that of determining tactics or strategy. Baldwin described the inner turmoil which besets today’s students—a choice between the assurance of safety in a white supremacist system or the dangers of struggle:

“Their moral obligations to the darker brother, if they were real, and if they were really to be acted on, placed them in conflict with all that they had loved and all that had given them an identity, rendered their present uncertain and their future still more so, and even jeopardized their means of staying alive.”

The ruling class is determined to make it as difficult as possible for the students to make this choice and to form a new identity in the process. It is why they have so viciously attacked the encampments, from the countless distorting and denunciatory statements by so-called authority figures, to the mass arrests and razing of the encampments, and now in the continuing and blatant censorship and intimidation of students. They encourage the students to doubt and fear, to try to forget, and to turn their back on humanity by abandoning the commitments they made in the spring. Although the university betrayed them, the students are offered retreat back into the university’s chilling, empty safety. There, cowardice, complacency, and self-centeredness will be handsomely rewarded; courage and the moral choice will wither on the vine.

What has been made apparent to the students is that even elite education does not grant freedom or enlightenment. They are being prepared to join a ruling class in symbiosis with war, which is impossibly broad in function: from the planning and funding of war, its defense in the media, its building of logistics and technological infrastructure, to its justification through the production of expert knowledge. All of their youthful vitality, their grand education, and even the purpose they seek, are to be channeled into conformity with the values of the State Department.

The university is but another apparatus of the state. And if the students refuse to play their allotted role in genocide—whether in silent complicity or with enthusiastic support—then they are worthless and to be discarded. Baldwin, describing rebellious college students during the Vietnam War era, wrote, “they had not realized how cheaply, after all, the rulers of the republic held their white lives to be… They were privileged and secure only so long as they did, in effect, what they were told: but they had been raised to believe that they were free.”

He saw then, though, that many were still “deeply corrupted…by the doctrine of white supremacy in many unconscious ways,” and “were far from judging or repudiating the American state as oppressive or immoral—they were merely profoundly uneasy.” Indeed, the white anti-war movement took on momentum and prominence with the protest of the draft; and while Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the New Left drew from the energies of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, they remained distinct and even at a distance. A color line existed amongst those who were for peace: those who looked to Noam Chomsky and Jane Fonda occupied a different lifeworld from Martin Luther King Jr. and Muhammad Ali.

The anti-Vietnam War student protests are often invoked as an easy comparison to this past spring, but in many ways, the students today are willing to go further than the “flower child” generation of the 1960s that Baldwin witnessed. In the spring of 2024, many students made a leap. Some went for broke. They did this not for themselves, to avoid being drafted into a war, but because they were strongly driven by a moral imperative. As they looked on a genocide, widely condemned by the world, they had to question the moral health and political future of a state which continues to fund 70 percent of Israel’s war effort. They had to act.

These students rebelled against the standards of the elite university, which upholds whiteness—not as a racial category, but as an ideological invention dissociating a select few from the general, universal human condition. Students rejected the assumption that they uniquely deserved protection, refusing any distinction between themselves and the Palestinian people. Indeed, they profoundly identified with them, declaring their fates were linked. They face, on the whole, more severe consequences: suspensions, expulsion, eviction, blacklisting from jobs, and even deportation. But they say in response that no price or pain inflicted on them by the ruling class can compare to the suffering of the people of Gaza.

The Possibilities for the Palestine Movement and the American Future

Today, the Palestine solidarity movement faces a crossroads. For years, the oppression of Palestinians by Israeli occupation lingered on the fringes of general consciousness. The past year has marked a watershed, with public conscience becoming awakened and opinion passionately shifting against Israel in favor of a real ceasefire, peace, and the establishment of a Palestinian state.

But such developments have been marked by the ruling class’s suppression and hostility the whole way—what has been called a “Palestine exception” of unequal treatment. The students especially have been disparaged and belittled, and their ultimate goals and intent have been distorted. The ruling elite fearmonger in an attempt to narrow the possibilities for struggle and isolate the students and the movement.

Almost every other “progressive” cause for social change in the last decades became absorbed into the Democratic Party as it reached critical mass. Black Lives Matter, the LGBTQ movement, feminism, the climate crisis, and even socialism were appropriated by Democratic campaigns. The Party, as an establishment, swallows up progressive causes—and dictates what counts as “progressive”—to bolster its image. Amongst prominent Democrats, there are shockingly few sincere champions of these causes in practice. The ruling principle is a calculated strategy to leverage a veneer of cultural progressivism against the apparently backward Republican Party. For instance, the George Floyd protests won Joe Biden the presidency in 2020; for the 2024 election, abortion rights were substituted as the main cause—a strategy that has now failed.

Unlike other movements that the Democrats have taken up for political advancement, Palestine cannot be satisfied by rhetorical inclusion. Palestine and Gaza ask fundamental questions of war and peace, with a concrete demand that must be answered in deeds, not in words.

The Democratic Party’s inability and refusal to reexamine its symbiotic ties with Israel—even as it commits crimes against humanity and destroys its legitimacy in the eyes of the world and its own base—reveals the Party’s most uncompromisable interests and ideology. These interests have been hitherto obscured by a performative, weaponized dedication to general human welfare. But it is becoming evident that the greatest interest of the Democratic Party is an increasingly naked and existential commitment to war.

In the spring, there were tens of thousands of students who were passionate, willing to sacrifice. Each of them also made a commitment: every student who was serious then about ending the genocide knows they cannot easily abandon their moral principles. They must now grapple with their long-held assumptions and with their own inner conflict—what to do, how to do it, and where to place their faith so as to succeed? But regardless of their inner feelings at any stage, the students’ task—their raison d’être—is to end the genocide. This will define their ultimate success or failure, and their next steps.

Their two main options are either to be narrowed, or to broaden.

In the former, the Palestine movement can allow itself to be pushed back to the margins of society, dissipating on the mass front into a toothless cultural liberalism. The ruling class’s siege on the most committed, radical students is meant to isolate them from their mass base and turn them away from democratic struggle. This alienation is the desired outcome of the ruling elite: the extreme and adventurist Weather Underground went this route, splintering off from the fading SDS; neither resulted in meaningful success. The present-day Palestine movement has been touched by strains of anarchism, ultra-leftism, and experiments with guerrilla tactics; but on a general level almost everybody carries the woke ideological baggage of the last decade, making them vulnerable to virtue signaling and regression towards empty moralizing.

If the student movement becomes totally cynical about America—viewing it as a settler colony identical to Israel and bombastically advocating for its dissolution—the movement will flatten the complexity of the political landscape and condemn itself to the fate of nihilism: stagnant, pessimistic, with no political horizon or vision of the future. But as long as there is any love in the movement—love of Palestine, love of humanity—the students will be driven, with good faith, to find a path that can lead to freedom.

A broad peace movement presents a larger and more durable alternative. The encampments demonstrated the presence of both hunger and energy in American society for new political expression and new ways of relating to one another—a movement to unify and develop the wide-ranging and growing anti-war sentiments of the American people in a principled manner. With this recognition we are drawn closer to the Black Freedom Movement, which broke the stranglehold of assumptions governing the human being’s relationship to society; and reshaped this relationship on freer, more just terms of positive peace. We are compelled to know the Black proletariat, whose consciousness forged the American revolutionary process. Students have clearly displayed an interest in reaching out to the broader community; and while divestment campaigns remain important, the most revolutionary thing the students can do is try to find the people.

During the Civil Rights Movement, Baldwin was driven by a powerful belief in the capacity of the American people. He proclaimed: “We are here to begin to achieve the American Revolution. It is time that we the people took the government and the country into our own hands. It is perfectly possible to tap the energy of this country. There is a vast amount of energy here, and we can change and save ourselves.”

We must do the same and urgently reach a higher stage to fulfill our commitments. To do so, we will have to understand ourselves, and love the people of this nation, discovering a new identity in the struggle for a new society. It will require creative experimentation, discipline, and steadfastness to define us. A long road lies ahead, with difficult choices for people to make—but in the end, we cannot evade these choices without evading life itself.

Leave a comment