We live in times that seem desperate, violent, and tragic, yet hopeful. Even as the world passes through a period of erupting violence, a horrific genocide in Gaza and an overdrawn war in Ukraine, the Western world’s sun is setting. Through these conflicts the American ruling elite tries to hold on to a time that is ending: one of its unchallenged domination. We are moving on to a time that contains the seeds for a new world order, a new stage in the development of world democracy. No one who has witnessed the recent BRICS summit at Kazan can deny this possibility. Those who feel this most keenly are the colored masses of the world. Having overthrown colonialism one or two generations ago, the children of that political freedom have now become the first to receive an education, to reach economic and social stability. The darker world stands at a precipice of a new colored modernity.

This new stage will not be the modernity outlined by Francis Fukuyama; it will not fulfill the manifest destiny envisioned by the white world. Rather, it will be defined by the darker masses of the world who have achieved a voice in their own affairs, and in world affairs for the first time. The societies and social systems of much of the Third World, especially India and China, have undergone many profound changes in the last 75 years. There has been widespread urbanization, and the development of a robust and stable middle class. On the other hand, the rural is no longer isolated or untouched by the fresh air of information. The village knows what happens in Delhi, or Seoul, or New York. There has emerged a new consciousness among the people, who are becoming aware of themselves in the world.

The masses of these people are not white, nor do they crave to live with white standards. They carry with them deep rooted traditions and ideas of beauty. They do not want to look like they have been dressed by Zara, or want to eat at Jewish bakeries. They do not fetishize the material world, and largely do not depend on things or labels to know their self-worth. They carry with them ancient religion and morality, not easily uprooted from their lifeworlds, despite hundreds of years of Western colonialism. Perhaps even more significantly, they carry with them the memory of their struggles for liberation in the 20th century, a bastion against Western ideas of progress and success.

What then will modern Afro-Asiatic societies look like? I will argue in this essay that colored modernity has its first example in the African American experience, and the Black social system that is forged from it. Modernity all over Africa and Asia will follow certain social patterns that have their first expression in Afro-America and will look more like the Black American lifeworld than Europe or white America.

Afro-America: Colored Modernity

The African American people were brought to the New World in chains, and their ties to their civilizational roots forcefully and brutally severed. Yet, in their uniquely American experience, they created from that rubble a new civilizational foundation. The social system and lifeworld of the African American people has been studied in depth by Black sociologists and intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois, E. Franklin Frazier, and Angela Davis. I will attempt here to recount some of the main points that serve our argument of a new colored modernity.

First, under slavery, the Black family unit was under constant attack from the slave owners. The treatment of these human beings as chattel never allowed the traditional family unit of the Afro-Asiatic world to re-establish itself. Individuals were bought, sold, and moved around with little to no regard to their emotional attachments to family members. While in general no family relationships were respected, the mother-child relationship was allowed to exist in some ways more than the father-child relationship. Black mothers and children were sometimes treated as a unit. Rape was legal in slavery, and children between slave masters and Black women were common. Even after Emancipation, marital ties were always loose, as men often left homes to search for work. As E. Franklin Frazier lays out in his seminal work The Negro Family in the U.S., what emerged from Black people’s struggle against this system was a matriarchy where the mothers, and significantly grandmothers, would serve as heads of the family. Even today, under the white supremacist U.S. state, one in four Black men are likely to be incarcerated at some point in their life, continuing the historic attack of the U.S. ruling class on Black men.

Another effect of the attack on the family unit in slavery was the absence of traditional roles for women in the household that exist in much of Asia and Africa. As Angela Davis argues in her book Women, Race, and Class, slavery allowed no distinction between men and women with respect to the work on the plantation. Women were expected to work as hard as men, bearing the additional burden of childbirth. Women would work through their pregnancies. Thus, Black women were, from the very beginning of their American experience, workers. As part of the proletariat, even after Emancipation, they never came to accept their role as traditional wives or mothers, which white women performed in the same nation. Black women, ironically, were freed from the bonds of patriarchy to an extent by their role in the slave workforce. This means that women in the Black community have always had a consciousness that was qualitatively different from women in the Afro-Asiatic villages. They are assertive and confident. Most notably, their role as equal partners of Black men in the struggle for Black liberation has never been in question.

This reflects itself prominently in the relationship between men and women in the Black community. It can be argued that men and women are seen as equal partners, with women often defining the terms of their relationships. Black women have not been a part of the feminist movement for sexual freedom in America because their relationship to Black men does not necessitate such a struggle. White feminism does not question white supremacy directly, and Black women do not see themselves ultimately in the struggle for sexual freedom. Polyandry is not uncommon in the black community today, with children often being raised by mothers with external support from the father. This is in contrast to women of the Afro-Asiatic world, whose struggle to be freed from traditional roles in the home was part of the anticolonial struggle. Yet all the questions of the emergence of a new Afro-Asiatic man and woman from the ancient clan structures (and their distortion by colonialism) could not be settled as the newly freed nations struggled against crippling poverty and illiteracy.

Perhaps this different man-woman dynamic is made most clear through a study of Black music. Sexual themes are very common in the music of women Blues singers such as Ma Rainey, Billie Holiday, and Dinah Washington. In this music, the women do not describe themselves as shy or coy, but openly call on men to rise to the challenge of their relationship. They are not bashful about wanting sex or pleasure, and explicit in their wording. On the other hand, Black men musicians such as Teddy Pendergrass, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson, and Otis Redding display a kind of tender sexuality in their music, in contrast to the harsh and crass images of manhood in the white world. In this music is expressed the Black romantic ideal, which places romantic love in relationship with a higher consciousness, a love for humanity and God.

As mentioned before, the Black family unit was not allowed to thrive under slavery. Yet, what did establish itself in American soil during slavery was the Black community through the practice of Black religion. As Du Bois argues, “The black church precedes the black family on American Soil.” This church, in Du Bois’s words, was everything African. The Black church was not only a religious institution, but served as a place of relief and release from the pressures of slavery. Even more significantly, it served as a place of organization, and a place of struggle for Black people. This role of the Black church would reach its peak in the Civil Rights movement. The theology of the Black church, then, was different and maybe even a negation of white theology in America which sought to justify the race hypothesis. It placed its emphasis upon freedom, and love. Perhaps the closest parallel to this liberation theology was Gandhi’s satyagraha, but even then Gandhi was struggling against conservative streams of Hinduism, a product of the colonial era, that did not see religion as a place of struggle. In contrast, the mainstream of the Black church pushed towards the struggle for freedom. In sum, the Black church melded together the political, spiritual, and ideological to more fully capture the experience and imagination of its congregations.

The church also cemented another aspect of Black life: the collective raising of children. At its best, adults in the Black community see all Black children, and even sometimes children of other races, as their own. The constant onslaught from the white world created a special tenderness in the community towards children, who ultimately could not be protected against white oppression. As Baldwin writes, “The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality.” Black children are celebrated in the community when the community is strong. They are empowered to speak and express themselves, and every victory (birthdays, school graduations) is celebrated. This is against the backdrop of violence, especially police violence, which threatens to end every child’s life too early, or to lock them away in prison.

Another aspect of Black life I want to highlight is the conceptualization of the human being in society. Amiri Baraka argues in his work Blues People that the development of the blues in America can be traced as being parallel to the development of the African American. As blues music emerged from more primitive folk and work songs, using a language that was distinctly African American, so the African American people emerged from the Africans in America. Further, the blues are essentially a personal, an individual music, distinct from more communal folk forms. As Paul Robeson writes, “While Spirituals, work songs and songs of protest are collective creations and are performed collectively among the people, the blues (that is, lyrical songs, most frequently about love) express the emotional state of the individual.” The blues, in other words, articulate the experience of the Black human being in America. Thus they reflect a consciousness that is based on the unit of the human being, but not detached from the collective people or struggle he or she is part of. Despite being individual in their expression, they are not individualistic. We will come back to this aspect, since this unique view of the human being that exists within the context of the group and its struggle must be a feature of colored modernity. Lastly, Black music that draws on the blues, rhythm and blues, or jazz for example is a distinctly urban music.

Further, the tradition of blues in Black music can be seen as the first exercise in the autobiography of Black people. This was developed further by African American writers such as Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and others in novels, short stories, and essays. African American music and literature may be the first expression of autobiography for the world’s dark proletariat. As Baldwin says in his Uses of the Blues, “I want to talk about the blues not only because they speak of this particular experience of life and state of being, but because they contain the toughness that manages to make this experience articulate.” He says further, “These artists [Ray Charles and Miles Davis], in their very different ways, sing a kind of universal blues, they speak of something far beyond their charts, graphs, statistics, they are telling us something about what it is like to be alive. It is not self-pity which one hears in them, but compassion. And perhaps this is the place for me to say that I really do not, at the very bottom of my own mind, compare myself to other writers. I think I really helplessly model myself on jazz musicians and try to write the way they sound. I am not an intellectual, not in the dreary sense that word is used today, and do not want to be: I am aiming at what Henry James called ‘perception at the pitch of passion.’” Owing to the special racial oppression of the U.S., Jim Crow laws, and the one-drop rule, educated Black artists remained proletarian in their consciousness and imaginary. Artists such as James Baldwin can be seen as the first voice of the world proletariat in becoming, and Black writing can be seen as the precursor to a new kind of literature that will emerge from among the darker races as the proletariat becomes aware of their role in history and script history consciously. The literature that will emerge from their articulation of their experience will form a new kind of autobiography of a people.

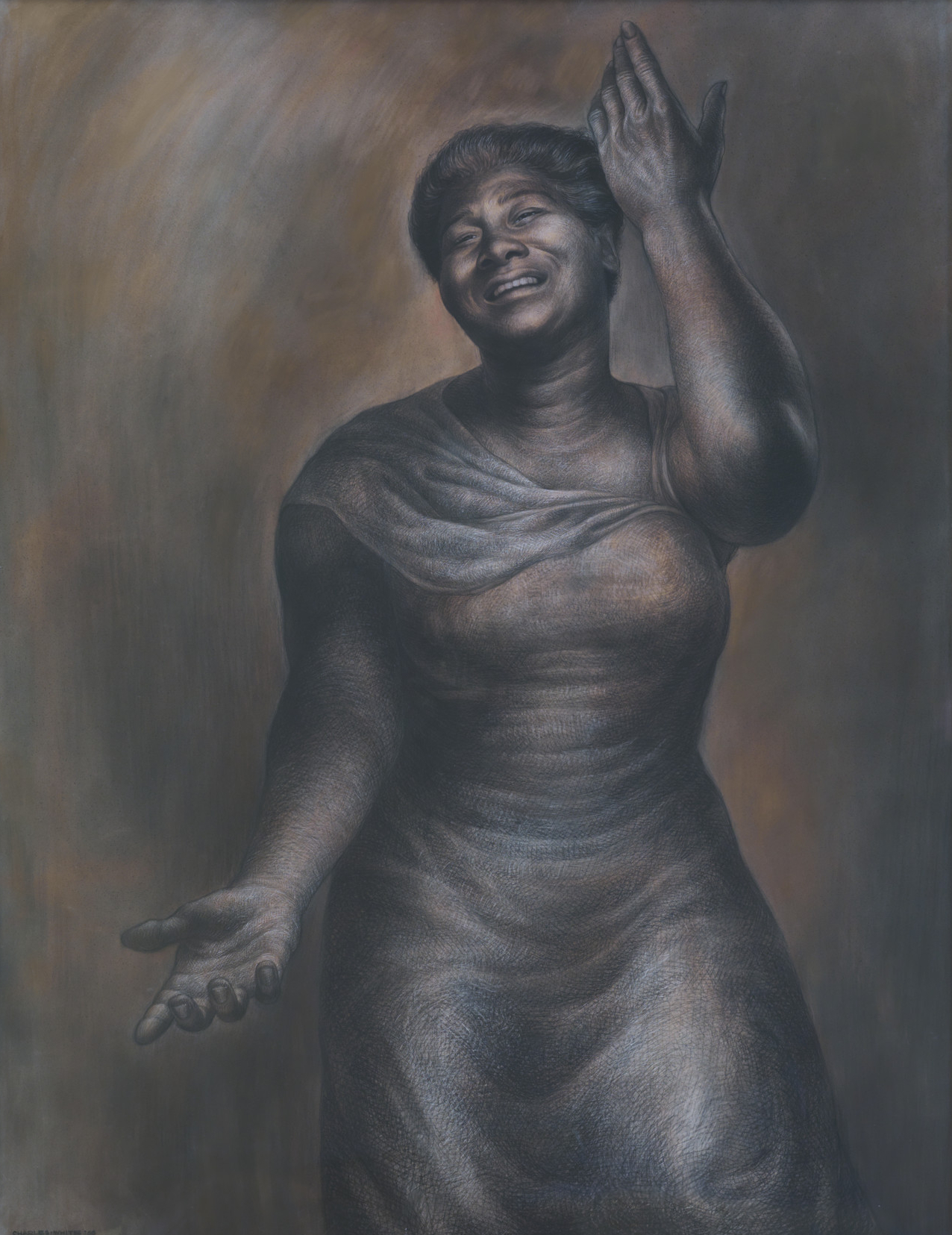

Left: Charles White, Bessie Smith, 1950. © The Charles White Archives.

Right: Charles White, Mahalia, 1955. Collection Pamela and Harry Belafonte.

I have tried to illustrate what emerges from a sociology of Black America that does not reduce Black life to stereotypes: one of a people who have undergone a rapid development of a system of values and Black social system in the struggle to survive. I would like to conclude this illustration with the Black view of white life. Their extreme and direct experience with white oppression has allowed Black people to question in fundamental ways the assumptions of white society. As Baldwin says, “The American Negro has the great advantage of having never believed the collection of myths to which white Americans cling: that their ancestors were all freedom-loving heroes, that they were born in the greatest country the world has ever seen, or that Americans are invincible in battle and wise in peace, that Americans have always dealt honorably with Mexicans and Indians and all other neighbors or inferiors, that American men are the world’s most direct and virile, that American women are pure. Negroes know far more about white Americans than that; it can almost be said, in fact, that they know about white Americans what parents—or, anyway, mothers—know about their children, and that they very often regard white Americans that way.” Much of the Afro-Asiatic world still is grappling with questions or stages of social development that African Americans have had to necessarily settle. What is most concrete in Black American life—the white man—can be more abstract in Africa or Asia. Is European Modernity the only modernity? The resounding answer from Afro-America is No.

What is Modern?

Francis Fukuyama’s work The End of History and the Last Man lay the basis for the triumphant West’s declaration that the development of human history had indeed come to an end with the crushing of the Soviet Union, and the victory of the Western liberal democratic state. Human beings, and in particular, white human beings, had reached the perfect social and economic system that captured the human search for Truth. White civilization had done it, and now the rest of the world just had to catch up to their perfection.

Fukuyama’s book builds the argument that just as Hegel had theorized, there is in fact a Universal History of Mankind. This is a history with a direction, as humanity moves to higher and higher stages of development, despite setbacks. He identifies this forward development with the course taken by Western nations, with the West’s material prosperity and its evolution to liberal democracy. He investigates the Mechanism by which this progress takes place, in other words, the motor force or driving force of history. He identifies Science and its product, technology, as the core of this Mechanism.

Yet this time calls for a profound re-thinking of Fukuyama’s thesis. The West is in decline; materially, in the community of nations, and ideologically. Western intellectuals are “unable to turn the key in the lock” having developed modern science, as Paul Robeson had predicted. They must rely on Indian and Chinese graduate students to carry out their scientific and social scientific research. The Western ruling elite has lost all semblance of rational or liberal thought, pushing the world to the brink of nuclear war that could end humanity. It is in this time that we must examine the thinkers that critiqued Western modernity and conceptualized alternatives.

We critique Fukuyama and Western thought without collapsing into postmodernism and subjectivism. There is indeed a Universal History of Man, which takes into account “the experience of all times and all peoples.” This history does present a direction, but the question demands to be asked, whose history is indeed Universal History? James Baldwin puts the white man’s History in contrast with Time,

She must change.

Yes. History must change.

A slow, syncopated

relentless music begins

suggesting her re-entry,

transformed, virginal as she was,

in the Beginning, untouched,

as the Word was spoken,

before the rape which debased her

to be the whore of multitudes, or,

as one might say, before she became the Star,

whose name, above our title,

carries the Show, making History the patsy,

responsible for every flubbed line,

every missed cue, responsible for the life

and death, of all bright illusions

and dark delusions,

Lord, History is weary

of her unspeakable liaison with Time,

for Time and History

have never seen eye to eye:

Time laughs at History

and time and time and time again

Time traps History in a lie.

But we always, somehow, managed

to roar History back onstage

to take another bow,

to justify, to sanctify

the journey until now.

Time warned us to ask for our money back,

and disagreed with History

as concerns colours white and black.

Not only do we come from further back,

but the light of the Sun

marries all colours as one.

Baldwin is asking us to question the lie that the White world has contorted History into. Baldwin is telling us that Time, which reflects the reality of the darker world, has never accepted the way in which History is made to parade in order to justify their oppression. Darker people all over the world will reject in Time the notion that they must catch up to Western liberal democracy. W.E.B. Du Bois’s The World and Africa also addresses the lie of white History. Du Bois says, “A system at first conscious then unconscious of lying about history then distorting it to the disadvantage of the Negroids became so widespread that the history of Africa ceased to be taught, the color of Memnon was forgotten, and every effort was made in archaeology, history, and biography, in biology, psychology and sociology, to prove the all but universal assumption that the color line had a scientific basis.” Hence, for thinkers such as Baldwin and Du Bois, European and White modernity is built upon the exploitation of the darker world, and the claim of Western superiority rests on the denial of this fact. Fukuyama analyzes Hitler as an anomaly in the trajectory of Western History, while Du Bois and Baldwin saw Nazism as a logical extension of white supremacy and colonialism. One wonders how Fukuyama understands today the Israeli state, as maybe another anomaly?

Du Bois explores in his unpublished manuscript Russia and America social systems and forms of governance that could emerge from within and serve the darker world. He says, “It would take a new way of thinking on Asiatic lines to work this out; but there would be a chance that out of India, out of Buddhism and Shintoism, out of the age-old virtues of Japan and China itself, to provide for this different kind of Communism, a thing which so far all attempts at a socialistic state in Europe have failed to produce; that is a communism with its Asiatic stress on character, on goodness, on spirit, through family loyalty and affection might ward off Thermidor; might stop the tendency of Western socialistic state to freeze into bureaucracy. It might through the philosophy of Gandhi and Tagore, of Japan and China, really create a vast democracy into which the ruling dictatorship of the proletariat would fuse and deliquesce; and thus instead of socialism even becoming a stark negation of the freedom of thought and a tyranny of action and propaganda of science and art, it would expand to a great democracy of spirit.” Indeed, Western critics have been predicting the collapse of the Chinese state since its very foundation. Yet, modern China has shown that social and political systems can differ in their paths to achieving democracy. As the rest of Asia and Africa rise to a new standard of living, democracy will be achieved through varied civilizational trajectories that will be determined by the masses of these civilizations. Despite talking repeatedly about “democracy” Fukuyama and liberal theory fail to realize this fundamental fact. Indian democracy, for example, will have to contend with its non-violent inheritance, as well as what D.D. Kosambi calls “a living prehistory.”

Thus, History is being written as we speak. It is being written by the masses of Russia and China in their support for their governments’ move towards de-dollarization. It is being written in the actions of the Axis of Resistance against Israel. The Universal History of Mankind yet has many questions to work out, and these will be settled in practice, by the forging of a new colored modernity. What will drive us towards this modernity? As Fukuyama challenges us, what will be its Mechanism?

When Rabindranath Tagore had visited China in 1924, a group of young activists criticized his visit, arguing that what China needed was not “ancient wisdom” but Western modernism, science, and democracy. To this Tagore had replied, “The revelation of spirit in man is truly modern: I am on its side, for I am modern.” He challenged his critics: “If you want to reject me, you are free to do so. But I have my right as a revolutionary to carry the flag of freedom of spirit into the shrine of your idols—material power and accumulation.” What Tagore was pointing to was that science and technology are but tools for the nurturing and growth of the human spirit; it is always the human being who thinks that is the driving force of history. Martin Luther King Jr. would criticize Western science for becoming rapacious without commensurate spiritual progress. He said, “The richer we have become materially, the poorer we have become morally and spiritually. (…) Every man lives in two realms, the internal and the external. The internal is that realm of spiritual ends expressed in art, literature, morals, and religion. The external is that complex of devices, techniques, mechanisms, and instrumentalities by means of which we live. Our problem today is that we have allowed the internal to become lost in the external. We have allowed the means by which we live to outdistance the ends for which we live.”

The Western ruling elite believe that human capabilities have been exhausted. They have nothing but contempt and disdain for human creativity, as can be seen from the Nobel prizes awarded to work in artificial intelligence this year. They think that the future of creative work rests upon machines and technology. We argue, building on Tagore and Martin Luther King Jr., that the motive force of history is not scientific development but the democratic emancipatory struggle of the masses of the world’s people. Human consciousness of the masses of people and its struggle to assert itself forms History. It is through this struggle that human consciousness itself can reach new modes and levels. Science must be harnessed and controlled by the spiritual ends of man to become truly revolutionary. Jawaharlal Nehru of India was influenced deeply by the formulations of Vinobha Bhave that in the modern age politics and religion would give way to science and spirituality.

The modern period will be marked by the dark human being coming into his own. His or her consciousness will not be the consciousness of Western individualism, for it will not be overdetermined by the extreme narcissism of a colonial empire. It will find ways of being and acting in the world that can address individual creativity and expression, with service to and the cohesion of the collective. In order to do this, the paradigm of Western individualism and liberal democracy must first be dethroned and the veil of white supremacy removed from our thinking.

Only in Afro-America can one find an individual consciousness of this kind, which is not only different from the white American consciousness, but in many ways a negation of it. The Black struggle for freedom conceptualizes freedom in a collective, humanity-wide sense, while not giving up on the category of the human being. One can see this illustrated, for example, in the novels of James Baldwin.

In the ways I have tried to illustrate above, African Americans have created a Black social system that is uniquely modern, in many ways urban, and allows them to address the questions faced by human kind in the modern, industrial world. Men and women of the darker world will break away from earlier clan and feudal relations to ones which allow for their human aspirations, struggles, and desires to be expressed more freely. Further, they will have to struggle against what Baldwin calls a white way of life which is so readily adopted by their elite and used to put them down. This elite is tied inextricably to the Western world order, especially to the American university system that trains them ideologically. In the coming time, they will either have to reorient towards their own people, or perish into irrelevance with the white world. New social and ideological relationships will emerge in humanity, as religion and politics transform into spirituality and science. I contend that these will resemble more and more Black America. As the world moves forward, the African American experience must be studied and known by the world’s people. This article attempts to only provide inspiration and direction for further study and thought.

Leave a comment