We are living through a moral crisis in the world, and the genocide in Gaza remains at the forefront of our minds. The world is in a moment of transition and hence a moment of great violence and danger. It is a time that calls for a deep study of Martin Luther King Jr., the man who fought war with the weapons of love—with the sword that heals. Martin Luther King wrote in his essay “The World House”: “In one sense the Civil Rights movement in the United States is a special American phenomenon which must be understood in the light of American history and dealt with in terms of the American situation. But on another and more important level, what is happening in the United States today is a significant part of world development.”

The Civil Rights Movement was a part of the great upsurge of dark humanity crying out for democracy between the 1950s and 1970s. It may represent for us today one of its most advanced forms. This is not to compare narrowly revolutionary struggles all over the world, but to scientifically study the trajectory of revolutionary thought and ask what remains for us today a resource to expand democracy. Indeed, Martin Luther King represents the great gift of Black America to the nation being born within the U.S., but also a gift to the world humanity as a whole. In this essay I will try to argue that King’s inheritance must be taken up by Americans and young Indians alike. Although he learnt from the Indian tradition in his time, he may hold the key to Indians claiming their own revolutionary legacy in this time.

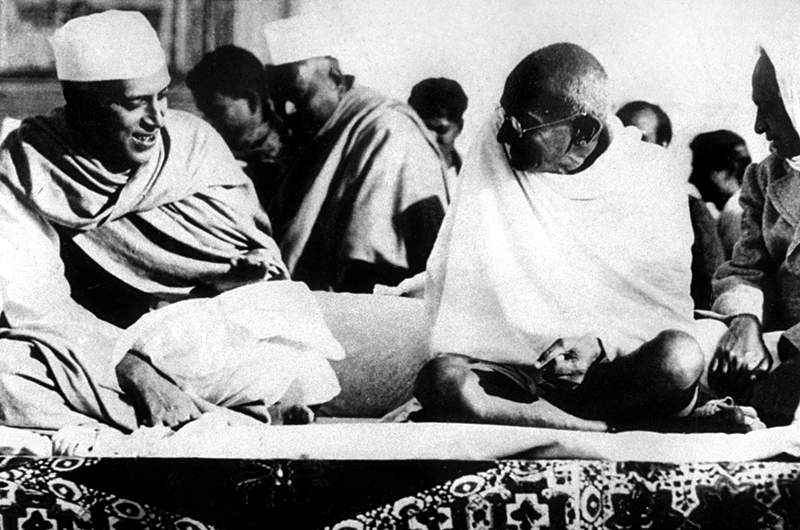

The first satyagraha, conceptualized and led by a young Gandhi, was born in 1907 in South Africa. After he returned to India, Howard Thurman and Sue Bailey Thurman would visit him to discuss the problem of the Color Line. Gandhi would prophetically say to them, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.” It is one of the most remarkable epics of modern history how the message of nonviolence and freedom was taken up by African Americans through the leadership of Martin Luther King.

How did King “apply” Gandhi’s methods to the society he lived in? It was no dogmatic application, but a creative synthesis that in substance allowed the African American struggle to advance the ideas of the Indian Freedom Movement. The synthesis involved the work of the cadre of transformed nonconformists in the Black Freedom Movement such as Diane Nash, James Lawson, Coretta Scott King, Fred Shuttlesworth, Ralph Abernathy, King himself, and many others. This synthesis found expression in the sermons and speeches of King.

This time of acute political and social crisis in the U.S. calls for the young generation of Americans to take up a study of the Black Freedom Movement, and to complete the revolutionary process that would make Martin Luther King the father of a new American nation. This would require the youth to break away from patterns of narrow politics of the Trotskyite Left, identity politics, cultural nationalism, and short sighted economism to claim their own revolutionary legacy. Further, a new understanding of the American revolutionary process, as put forward by W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King, James Baldwin, and more recently Anthony Monteiro, will form an essential basis for this study.

On the other hand, Gandhians in India and all over the world would benefit from a deep study of the Black Freedom Movement to break away from the ritualism that surrounds the practice of Gandhianism today. The question facing us is not one of vegetarianism, cleanliness, khadi, or even inner spiritual transformation away from outward engagement, but is the question of action to transform an unjust world. When Diane Nash says, “The only person you can change is yourself. When you change yourself, the world has to fit up against the new you,” she is speaking of transformation that comes with unacceptance of an unjust system. Gandhi’s method of revolutionary change cannot be applied by trying to copy Gandhi in form, but requires a political and social analysis of the present world, clarity on the task at hand, and a firm moral commitment. We cannot deal with the present being intellectually lazy, but must instead engage in rigorous study of the past and the immense resources it offers us.

What is a Revolution?

The history of revolutions in the modern epoch begins with the American and French Revolutions to overthrow monarchy, and the Haitian Revolution led by liberated slave workers. Both the American and French Revolutions established universal human values, that all men were equal. These revolutions gave us the concept of democracy, the rule by and of the people. Yet both remained incomplete. The French Revolution was taken over by a bourgeois class which established capitalism. The American revolutionaries could not make the promises of their revolution real, for they compromised with slavery, refusing freedom to the millions of slaves that should have been citizens under democracy. The American Civil War which dealt partly with this contradiction was followed by the remarkable revolutionary processes of Black Reconstruction in America. The year 1917 saw the Russian Revolution, the first socialist revolution which took Russia directly from Tsarist rule, a relatively backward economy, to the building of socialism supported by workers and peasants.

These were followed by the anti-colonial struggles, and the Indian and Chinese Revolutions of 1947 and 1949. In this history of revolutionary action, India stands out as both the first anti-colonial revolution to break out of imperialism, and also the first conscious example of nonviolent direct action on a mass scale that led to a change in state power. Before the Indian revolutionary process, revolution had always been synonymous with a violent overthrow of the ruling elite. It could, however, be argued that the general strike was an initial form of civil disobedience, including the collective actions of African Americans during the American Civil War. Lenin had theorized that revolutionary processes would take place with a smashing of the state by a class that could not accept their rule any longer. In India we saw a peaceful revolution, where the British were compelled to leave India in the hands of Indians because the masses nonviolently refused to accept imperial rule.

The question of how the Indian Freedom Movement must be characterized has been the subject of intense debate since. Was it a “transfer of power” from a white ruling elite to brown faces who continued the same characteristics of imperial rule? Was it a “bourgeois democratic revolution” that had to be subsequently followed by a socialist revolution to establish the rule of the masses? The answer to these questions becomes clear when you put the Indian revolution together with the Black Freedom Movement. They were both revolutions of a new type. They both represent to us the need for a new theory of revolution that can both explain and build on them. They cannot be understood in old categories, but are a departure in their very essence.

The legacy of the Indian revolution and Black Freedom Movement show us that revolutions cannot be defined purely in terms of the material basis of a society, but must be defined in human terms. “The burden of the material on man is ancient,” as Rabindranath Tagore said: it is man’s ideas that make him modern. The two movements show us that a revolution must be the raising of the consciousness of a people to a new stage, such that they do not accept old forms of rule, but demand a further expansion of democracy. Of course, an expansion of democracy must be accompanied by new forms of social organization and relations of production, but advances in the ideas and consciousness of a whole people may play a more central role in the revolutionary process for the 21st century than ever before. Further, revolutions must not be seen as events, but in a processual way. The Black Freedom Movement showed us that revolutionary change must not be envisioned as seizing of state power by one class, but by an expansion of democracy for the whole people. It was only through the freedom of the Black proletariat that American democracy for the whole people could be realized.

Emphasizing the human, Martin Luther King shows us through his life that the working class and poor cannot be understood as abstract categories, but must be understood in the concrete. His life’s work involved dealing with the oppressed in an existential way. He spoke regularly through his sermons and speeches to the anxieties, contradictions, and aspirations of the Black proletariat. Further, he challenged them to become better human beings, to become people who could challenge the systems of racism by refusing to participate in it. He saw, as Gandhi did, that bringing the people to a place where they had the confidence and ideas to reject the lies that had been told about them was not a trivial matter. He dealt with the poor as individuals rather than an undifferentiated mass.

King articulated through his brilliant oration much of what was symbolism in the Indian Freedom Movement. Gandhi was speaking to a largely illiterate and widely diverse peasantry, while King spoke to the Black proletariat that had a high level of consciousness shaped by their position at the center of empire. He took the ideas of nonviolence to a higher stage by framing them in the context of world philosophy and historic human development. He extended the ideas of nonviolence to international relations, speaking of an alternative form of world organization that was not dependent on coercion and war. King also conceptualized the nonviolent transformation of the American state from a war economy to a peace economy. He showed concretely how such a transition could take place through his work in the urban North of the United States in the last years of his life.

New forms of revolutionary processes gave rise to new revolutionary organizations in the Black Freedom Movement: the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. This was not a vanguard party in the Bolshevik sense. This was an organization that maintained high levels of discipline among its leadership but was organic to the Black church and operated through the networks of the church.

New forms and ideas are needed in a time when the Indian people, especially the young, are reaching new levels of economic stability, education, and literacy. The same is true for China. Our young now know of the world through their mobile phones, regularly interacting with American and South Korean propaganda on a mass scale. A much broader section of Indians now aspire to travel the world and learn of other peoples and cultures, seeing themselves as world citizens. On the other hand, malnutrition and hunger continue to plague India. Poverty remains the largest hurdle to human freedom in much of the world. Further, the world undergoes a crisis the likes of which we have not seen since the Second World War, and the ongoing genocide in Gaza weighs heavy on our minds. What must a Gandhian or Kingian practice look like at this time? The importance of the struggle of ideas cannot be overemphasized. For this, we must study the ideas of Martin Luther King, James Lawson, and Diane Nash.

In the formerly colonized nations of Asia and Africa, change is on the horizon. As the hold of the American empire weakens and new opportunities arise for global trade and exchange, reforms in the state will become necessary to overthrow neocolonialism and the control of those who collaborate with it from within. This must be a nonviolent process if it is to successfully lead to the realization of a state of the whole people. Further, in nations such as India or China, questions facing the individual have become more prominent—questions of purpose, moral progress, and engagement with the world. These are the questions of a new Afro-Asian modernity, distinct from Europe. The vision for the future in Afro-Asia must take into account the moral and spiritual progress of man along with technological progress. We must turn to Martin Luther King’s critique of Western science to guide our path into the future, for “if we are to survive today, our moral and spiritual ‘lag’ must be eliminated. Enlarged material powers spell enlarged peril if there is not proportionate growth of the soul. When the ‘without’ of man’s nature subjugates the ‘within,’ dark storm clouds begin to form in the world.”

Love and World Democracy

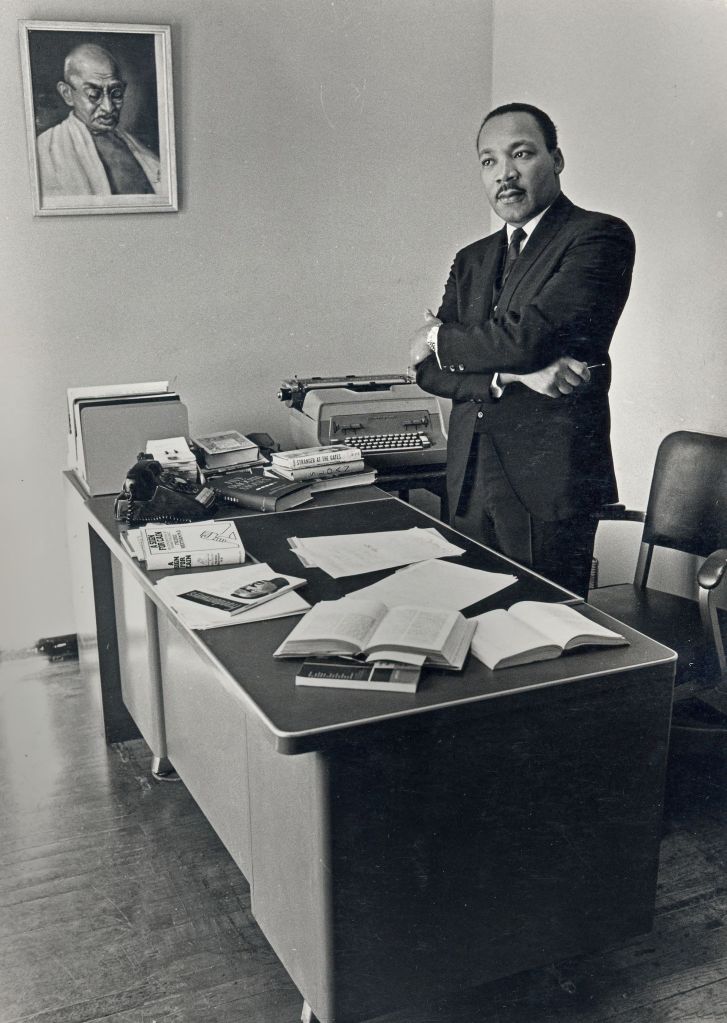

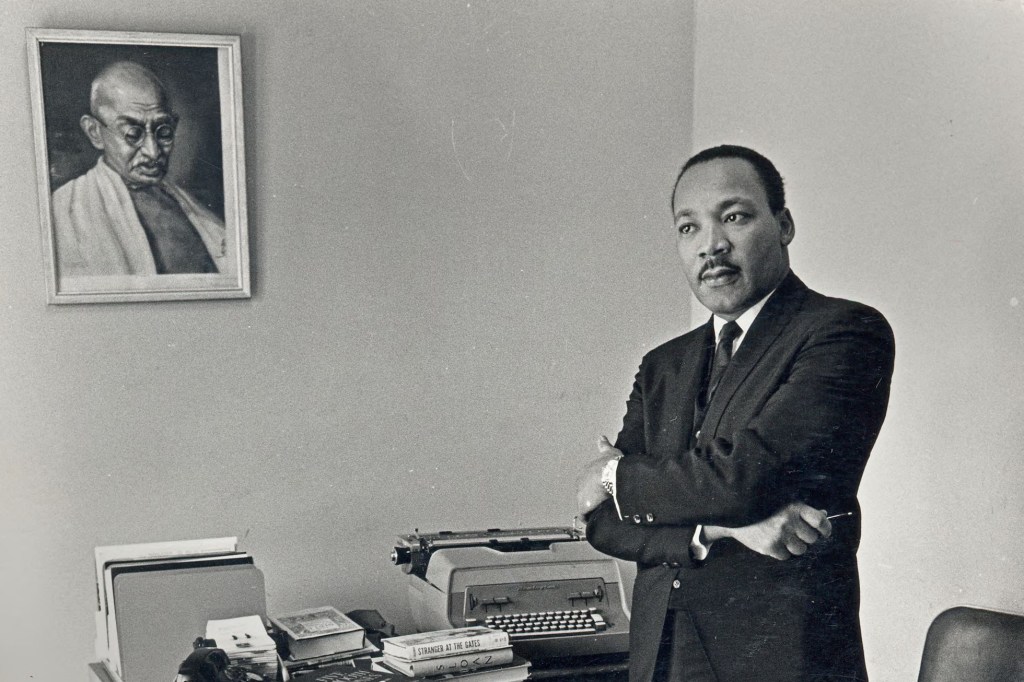

Central to Martin Luther King’s contribution to human freedom is love. Here both he and Gandhi moved away from European thought. Gandhi connected love to truth and change, while King put love in dialogue with power. King said, “Gandhi was probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force on a large scale.”

The cadres of the Black Freedom Movement were trained in nonviolent direct action and taught to love even the racists who did not see them as human. This love was not a weak and sentimental force, but strong and unyielding. The scenes from the Freedom Rides to desegregate interstate buses, or the lunch counter Sit-Ins in Nashville come to mind when one thinks of the love ethic of the movement. These young people never saw other human beings as the enemy. The enemies were the ideas that people held, which still could be changed through struggle. The movement realized that the American people had to be one people if they were to achieve their country.

In a speech given in 1955 to the people of Montgomery, King said, “If you will protest courageously and yet with dignity and Christian love, when the history books are written [in future generations], the historians will [have to pause and] say: ‘There lived a great people—a black people who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.’ This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility.” In his autobiography he writes, “One of the greatest problems of history is that the concepts of love and power are usually contrasted as polar opposites. Love is identified with a resignation of power and power with a denial of love. What is needed is a realization that power without love is reckless and abusive and that love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.”

Love as a social force had been spoken about by the leaders of the Indian Freedom Movement, Gandhi, Tagore and Iqbal. Yet today, politics at the national level remains overrun by realist considerations and narrow calculations of votes. We need once more at this juncture to study the ideas of Gandhi, developed further by King, that perhaps a new kind of social organization could be built: one not only on the values that come out of liberal thought, but on love. The question of history bears heavy in Asia, and civilizational roots must be taken forward in a meaningful way into the modern state. It has become clear to much of the world that Western liberal democracy will not fit Asian and African nations. What then will be our path? The temptation is ever present to lapse to a narrow cultural nationalism, to proclaim our past as static and great. The key lies in the moral dimension, so present in our histories, yet which remains elusive in our present.

Love becomes even more important now in a time when technological progress threatens to erase all that is human in favor of what is profitable and convenient. Individual freedoms and liberties will no longer be enough; our societies will need to be built on the fundamental truth that we must love each other. The diversity of a nation like India has so far been bound by the historical unity of castes and clan organization. As we move into the modern epoch and the young no longer identify with these forms of social organization, what will bind us together? We must teach the young the ideas of Gandhi and King: that love can form the basis of our unity, the driving force of our social strivings, and inject life once more into our civilizations.

This must be broadened even further. We live in a time when a nuclear war threatens our existence at every moment. We must study Martin Luther King’s work, and in particular his historic sermon “Why I Am Opposed to the War in Vietnam.” Here I quote from the same:

“Every nation must now develop an overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole in order to preserve the best in their individual societies. This call for a worldwide fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class, and nation is in reality a call for an all-embracing, unconditional love for all men. This oft misunderstood and misinterpreted concept, so readily dismissed by the Nietzsches of the world as a weak and cowardly force, has now become an absolute necessity for the survival of mankind. And when I speak of love I’m not speaking of some sentimental and weak response. I am speaking of that force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life. Love is somehow the key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality. This Hindu-Muslim-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist belief about ultimate reality is beautifully summed up in the first epistle of John: ‘Let us love one another, for God is love. And every one that loveth is born of God and knoweth God. He that loveth not knoweth not God, for God is love. If we love one another, God dwelleth in us and his love is perfected in us.’”

Following in King’s footsteps, we must speak out against the demonic actions of a desperate America and Israel in Palestine. We must build a new world movement for peace, and reform the institutions of international relations that have so far failed the children of Palestine. A new dialogue between the peoples of the world must be established, unmediated by the American ruling elite. A worldwide fellowship is the need of the hour, and we must look to Martin Luther King Jr.—revolutionary prophet, created by the descendants of African slaves—to guide the path to it.

Leave a comment