We are publishing a transcript of Dr. Anthony Monteiro’s opening remarks from the Saturday Free School’s December 23, 2023 session on Christianity in America and Its Undoing. The Free School meets every Saturday at 10:30 AM, and is streamed live on Facebook and YouTube.

Good morning everybody, I hope everybody’s enjoying the holidays. So many of the Free School people are all over the world in different places and we miss them and I’m certain they miss us. I mean, even if they’re in California it’s not Philly, you know I have to say this if you don’t mind, you know. California’s sunny and warm and beautiful. And Philly, not so beautiful, not so sunny, kind of gritty and dirty. But we got all the creativity, the music, the art, and of course the Free School.

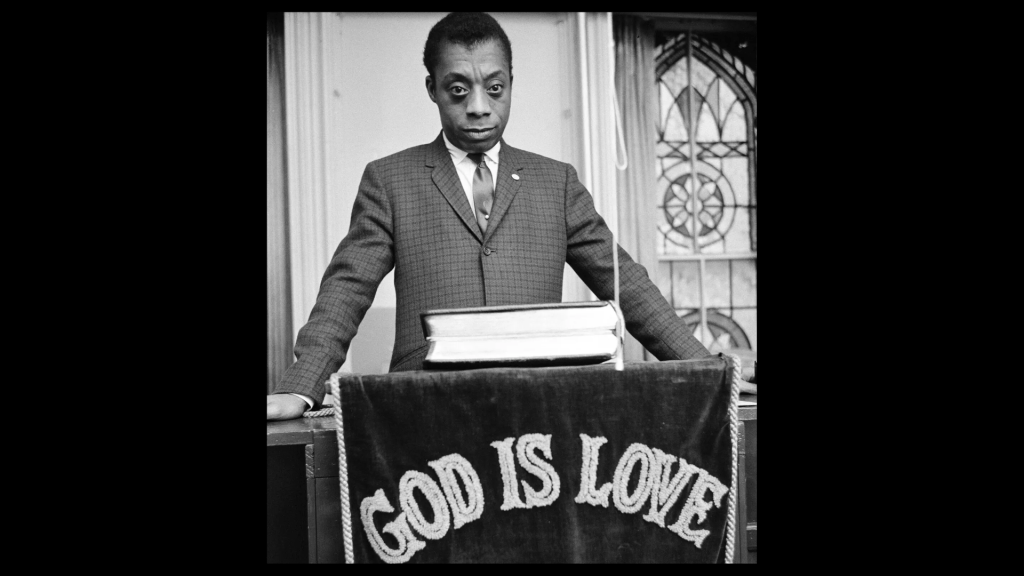

So we can’t wait for all of the members of the Free School to get back here. And we’re meeting online again because the Unitarian Church is closed for the holidays, and we’ll be meeting online next week as well I think. So anyway, this week we want to talk about the crisis in American Christianity and suggest some articles written by James Baldwin, and also to talk about the importance of this crisis to the democratic and revolutionary reconstitution of the American polity, the American political system.

Of course all of this occurs as we enter into the year of probably the most consequential election in American history. Everything is pretty much at stake or up for grabs. As I talk to Nandita and Raju and Purba and really to Sambarta’s parents, whom I hope to talk to more this coming weekend, really I do—this crisis is unfathomable. They can’t get their heads around it. If you are not here, it’s just incomprehensible that the most powerful nation, a nation which has been the most powerful nation in the world for over 75 years, is now in a crisis of decline and facing an election like the 2024 election. People just don’t get it. And that’s understandable, they have no references.

But I think even more than that, and this goes for—again we have to reference the American Left which is like a soldier that has been in many battles and has lost a leg, and an arm, and an eye and is barely limping along but trying to convince everybody that he’s still able to enter into new battles. But everybody knows that he is not. That’s kind of what the American Left looks like. They cannot comprehend this profound fragmentation of the country. And we’ve gone through this so often; perhaps I’m talking a little bit more because I’m talking to Emily’s parents, who are listening to us.

We’re in new territory. Part of the problem of the American progressives and American Left is that they act like they’ve never heard of James Baldwin, who authors a most profound investigation of the very problems that we will be addressing today. I’ll kind of give some essays, and I want to really thank Emily for sharing some essays with me last evening which will I think help us to look at this problem in a larger and in fact more accurate, more concrete way.

In the past two weeks, important articles have appeared in both the Financial Times and the New York Times on the breakup of what are called mainline denominations.

Just let me explain something about Christianity and Protestantism. Christianity on a global scale is much larger than Protestantism. The largest Christian denominations are the Catholic Church; its headquarters are in the Vatican in Rome and is headed by the Pope. There is also the Eastern Orthodox Church which is split into several denominations; the Russian Orthodox and the Ukrainian Orthodox. And then there is the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. But those are not as large as the Catholic Church.

The United States and U.S. Christianity was born out of what is known as the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, and we could say traces its roots back to a single event which was Martin Luther, the Catholic bishop who in 1517 posted on the main cathedral of a church in a German city, this list of demands. This was a protest against the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, which could have gotten him sentenced to death.

The word Protestantism comes from protest. The other thing is, the Protestant religions or denominations emerge in the period of the rise of capitalism and the decline of feudalism. In this sense then, American Christianity is quintessentially modern and capitalist, with all of the values of capitalism including individualism, the rights of the individual, the separation of the church from the state, and so on.

So American Christianity arises out of a revolution, and a long revolution, including many bloody wars and civil wars which often took on the form of peasant wars against landlords and against the aristocracy. This Protestant Reformation culminates in the French and American Revolutions, the high point of the Protestant struggle. And therefore when we talk about the early immigrants and the so-called founding fathers and the so-called pilgrims to the United States, they were fleeing the oppression and so on in Europe that emerged from these wars of religion, which are in essence wars of ideology.

It’s quite fascinating when you think about it. For example if you take the Quaker movement, or the Amish movement; we’re very familiar with Amish people here in Philadelphia and we’re familiar with Quakers, the “community of friends,” as they call themselves. They were revolutionaries who were defeated on the battlefield in the struggles against the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. And so they fled to the United States. And in fact the first anti-slavery protests in the United States were held here in Philadelphia, led by the Quakers. And they’re called Quakers because ritualistically, they did not adhere to the strict rituals of the Catholic Church. If you’ve ever been to a Catholic church, it’s very scripted. Quakerism was more the individual expressing his or her relationship to God. And so it was that America is a Christian country, but a Protestant country; it’s not Christian in the way let us say that Italy is, or France is.

And so, the revolutions against the Catholic Church were part of the founding of America and of the American Revolution.

So when it is said, as it is said, that America is a Christian nation, it is pretty much saying America is a Protestant nation—with Catholics—but it is a Protestant nation; the deep structure, the values of the nation, the architecture of the civilization is grounded in the values of the Protestant Reformation that began in Europe and in many ways was fulfilled in the United States.

And there are what we call Protestant denominations. For those who don’t know, unlike the Catholic Church where you have one church or even in Islam where they talk about the Ummah, the community of over a billion people in Protestantism, you have individual churches who come together in a denomination.

The American nation-state, the American civilization is framed, civilizationally, in Christianity. And even Catholicism is, in the United States, different than in let us say Italy or Austria or France. Because it is conditioned by the civilization in this country. So the mainline denominations—that is those churches that fall under a certain hierarchy, a certain set of ways of doing things, I’ll put it that way. There’s seven of them and they’re known as the mainline because they are the richest and most powerful Protestant denominations.

There are other Protestant denominations that do not fall under the mainline denominations. In other words, if you take Southern Baptist, they don’t fall under what are called mainline. If you take for example evangelicals, or even Pentecostalists, or if you take that whole group of Black denominations such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the National Baptist Convention. They don’t fall under the mainstream denominations, you see what I’m saying?

For example, the African Methodist Episcopal Church is the first Black denomination in the Western World, maybe outside of Ethiopia, in the world. It is free Black people in the late 1700s refusing to accept a discriminatory practice within Methodism here in Philadelphia. And they left, and one group formed a new denomination known as African Methodist Episcopals. And they were bringing together two denominations, so to speak: Methodism and Episcopalianism. And then wrapping it in an African civilization and cultural imaginary, I’ll put it that way.

And so today when we interact here in Philly with the AME Church, with Mother Bethel. Mother Bethel is the mother church, the founding church of the denomination. That denomination split and formed an offshoot known as the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. Paul Robeson’s brother was a pastor in that church, and a church in Harlem where Paul Robeson himself was funeralized.

Then, the most popular and largest body of Protestants in the Black community and of Black Christians are Baptists. Now, because the Baptist denomination starts in the South I think, and they’re known as Southern Baptist, and they’re all white; and their theology was always racist, pro-slavery—Black people formed the National Baptist Convention, and these are voluntary associations I should say. Where individual churches, and you go around Philadelphia, you see all of these Black Baptist churches—you see the “First Baptist Church,” and you’ll see the “First African Baptist Church,” and all of that. It’s so fascinating. And each of them is a self-defined, self-supporting congregational community that agrees to align with the National Baptist Convention. And so the largest group of Black Christians are Baptists, and the largest denomination of Black Baptists fall under the National Baptist convention.

If I could just say one small thing here. Martin Luther King, when the Civil Rights Movement was starting in Montgomery—you know, all hierarchies and structures have a very strong conservatism—and when King and the members of SCLC, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; very interesting, the name is not insignificant. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, they formed as a result of having been kicked out of the National Baptist Convention, who said that, “You rebels are trying to take over in the name of a social revolution, and you’re not paying attention to the Bible.”

So, King and them, these young rebels, formed their own movement within the Baptist Church—and remember King is a Baptist minister, his father was a Baptist minister, his grandfather; they were all Baptists because that’s the kind of the denomination of the religious theological movement that enslaved Africans and after slavery, were recruited to. Because, you know, most of the slave owners and most of the South were Baptists. Methodism, and this is very interesting, which comes out of England—the word Methodist comes from the word method. I guess you heard of the rapper Method Man, no connection—you never heard of Method Man? Okay, look him up. But anyway.

Methodism, from very organic, very simple reasons; the method of prayer, the method of worship. Quakers, we quake, we do crazy stuff, you know, which the Catholic Church would never permit. Methodism was one of the first Protestant denominations to oppose slavery in England. And many Black people, especially in the North, even during slavery were attracted to Methodism because of its anti-slavery stance. John Wesley and you know, there’s the college in New England called Wesleyan, it’s a Methodist College.

So, I say all of that just to give a sense of the deep and broad and historical and civilizational dimensions of this. And you cannot trivialize any of this because this constitutes the lifeworld of the American people. And I’m certain, you know, I’ll take like Emily or Alice, your parents come to this country. And I’m certain they’re still trying to figure this out, you know. It’s non-hierarchical. I’m certain Sambarta, and I hope to talk to your parents about this, it does not compute so easily. But it is the deep and long tradition of individualism and the revolution against aristocracy and hierarchy. And that’s what you have here.

Again, let me get back to the mainline denominations. They are Methodism, Episcopalianism, Lutheranism, Presbyterianism. And I forget the last two or three, but if you look it up do Wikipedia. These are what are known as the mainline denominations. They are kind of what one would consider the foundation of American Protestantism and Christianity. They have the colleges, the universities, the theological seminaries. And they constitute for American Christianity what the Vatican and the Catholic Church and Catholic universities are for Catholicism.

Now, everybody else is not considered mainline, but I say that to only get to this point. That a crisis of legitimacy within the mainline denominations can be considered or viewed as part of the crisis of legitimacy of the political system itself, especially at the level of elites. For example take Unitarian Universalists, a very small part of the American population and of American Protestantism.

But far more important in their ideological and theological definitions of the Christian or Protestant religion. Episcopalianism, very small, nowhere near the size of let us say the Southern Baptist denomination. But very influential. Influential because you take Methodism, the Methodist denomination—so many presidents, Supreme Court Justices, and so on come from the Methodists.

Now, the two articles are included in the email that we sent out, and they’re worth reading. The first is from the Financial Times. And it’s interesting, the Financial Times writes an article about a crisis in an American denomination. Unitarianism is a uniquely American denomination, I think founded somewhere in the 1700s.

The Unitarian Church has given the movements against slavery and and racial discrimination some of its best fighters and warriors. You know, Martin Luther King was fond of quoting from a Unitarian preacher, “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends to justice,” you’ve heard that. Well King was quoting the Unitarian pastor Theodore Parker. The Unitarian Church from its beginnings was anti-slavery. Martin Luther King first heard about Gandhi and the Indian movement and soul-force and so on from Hinduism, and the Indian independence movement from the Black president of Howard University, Mordecai Johnson at the First Unitarian Universalist Church in downtown Philadelphia; in fact where we meet these days.

King himself gave a sermon entitled “Three Dimensions of A Complete Life” at the Unitarian Church up on Lincoln Drive in Germantown, in Philadelphia. Two of the great martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement, James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo, were Unitarian Universalists. Both were killed in the fight against segregation.

So this church has always been anti-slavery.

The Episcopal Church has not ever been anti-colonial or anti-slavery, until it was all over and then they say, “Oh we apologize, and now we’re anti-slavery and anti-colonial.” Well you’re 100 years late but, you know, we accept the apology. Never been that.

And if you study the practices of the two, and of course we have because of our interactions with them, there is a difference. There is a difference. However, the Unitarian Universalist Church which is very progressive in the social progressive sense—and by that we’re talking about the postmodern period.

By postmodern we mean this period of ideas and ideology and philosophy which kind of rejects the movements of the past, i.e. the Communist, the Socialist, the anti-colonial, and all of the theories that go with that. And [postmodernists] would argue that the spearhead of the struggle are cultural issues such as gender, sexuality, a kind of way of identifying race as separate from the political economy and so on. A kind of individualist, identity-affirming project.

Let me just give you an example, you know, I’ll take the Black community. Gayness is not new in the Black lifeworld. Black people tend to be less anti-gay than white people, they really do. Because all of us were segregated and remained so, where would you isolate your gay daughter or son or nephew or cousin? Because we all have to live in a prescribed community. So gay and straight and trans and whatever you want to call yourself, we all live together.

And unfortunately with all of the claims and counterclaims, there is no oral or other histories, I don’t think, of living as a gay person in the Black community. The closest we come to it, in narrative and fictional terms is James Baldwin. And in the modern, postmodern “gay LGBTQIA,” Baldwin is not embraced. Or only embraced in certain limited ways.

Because he felt that the “gay” movement was really a white movement, and he says it, we can get into that but. The other thing is, I have to say, there is not yet a scholarship worthy of the great James Baldwin in the academy or whatever, there is not.

In the white world, especially in mainline Protestantism, the rules, the grammar of the lifeworld are more strict. And thus to be white is to adhere to the common values of the white world. Black folk, you ain’t gonna be white no kind of way, unless you light enough to pass for white. And then if somebody find you out, then that game is up. But anyway that’s a whole ‘nother story. There’s a whole practice used to be called passing. Passing for white, you know what I’m saying; white by day on your job, Black by night when you come home to your community and your family. But that’s another story.

The white world has, over this history, been strictly organized around a single concept which itself is a fiction, called whiteness.

Whiteness is a negative; it is not a positive identity. And hence its fragility. And in a crisis, whiteness does not carry the predictive outcomes and possibilities it did let us say 50 years ago. To be white meant you could live in a better neighborhood, meant your kids could go to college, meant that you had a better job, et cetera. If you were white.

But in a crisis like this one, whiteness does not carry that same power. And I dare say, immigrants who come to this country highly educated—I’m not talking about the poor people—but let us say from Asia, South Asia, East Asia. “Educate my children”—and Asians do that to the max, I’m finding out more and more. For the purpose of joining the white world.

And in many ways, second, even third generations of immigrants can outdo white people in whiteness. Which is a spectacle that’s interesting to observe, from the Black standpoint. Anyway, if whiteness doesn’t predict success, then for white people and for immigrants at the level of higher education and so on—then what value does it have?

So much of American civilization is this Protestant Revolution, the rise of the individual, you know, all of the positive things. The separation of church and state, the supremacy of law, “We’re all equal under the law.” This is all wonderful stuff. And revolutionary, and not to be trivialized in and of itself.

However, it could not resolve what became the central problem of Western and certainly of American civilization, and that is a problem of race and slavery.

This is the ghost forever haunting the American mind. And of course this is why Baldwin becomes this, I mean, unbelievable figure. Unbelievable figure. Because he interrogates, deconstructs, and exposes the consequences and the short lifespan of this identity known as whiteness. That’s why Baldwin comes off a bit as apocalyptic. But he is saying, “This cannot last.”

And so American Protestantism, founded in revolution, is forever haunted by its connection to slavery and racism. Now, two mainline—by the way I’m saying mainline and not mainstream; mainline is a different thing—mainline Protestant denominations are splitting apart.

Let’s start with the Unitarian Universalists. The articles, both of them say that what triggered the splits are the LGBTQ questions. And my first reaction is that is not even the main part of the crisis. LGBTQ is not an issue for Unitarian Universalists. Everybody accepts gay marriage, LGBTQ identity, the rights of LGBTQ, et cetera. Everybody in the Unitarian Church.

But what is the split about? And I have concluded that the split has to do with a more profound civilizational crisis. And the question of what is the future for American civilization, and what will American civilization look like. And who will decide that.

Now, this is the question of the people versus elites. These denominations in the last 40 years, maybe a little longer, have been taken over—let’s say, the Unitarians—by highly educated, university-educated elites. If you are not comfortable with their leadership, then you leave the Unitarians, and either become an individual person who lives by certain spiritual values and his or her own interpretations and so on. Or maybe you go to an evangelical church, or maybe you try to join a Black church, or maybe you go to Islam, or maybe you become a Buddhist.

But if you are not comfortable, whatever your views on any other cultural issues are, with a highly-educated elite—sometimes what we call the professional managerial class—if you’re not comfortable with them telling you how to live, and what you should believe, and what the future is. Or even if you feel that you guys have failed and you’re talking shit that somebody taught you at Yale University and we’re not interested in that, and we’re seeking, let us say, a deeper spiritual connection to humanity; what Martin Luther King called a cosmic companionship, you see I’m saying.

These two class and ideological orientations are irreconcilable. So that’s the way I see the Unitarian Church, which is really a small church—I think overall there are about 1.5, 1.6 million Unitarians in the United States. Although its footprint in progressive Christianity is very large.

Then there’s Methodism. It is the largest mainline denomination. It’s not the largest denomination among Protestants—the largest mainline. Its split is far more significant. Because it is more associated with mainstream American values, overdetermined by the elite presence in Methodism. Methodism has its colleges, its theological seminaries, its theologians and so on. They have regular conventions. They decide upon theological issues based upon these conventions and long and democratic discussions; I would say discussions are over-determined by elites.

Now, Methodism is a global movement. If you go to what they call the global South, let us say Africa—Methodists in Africa do not carry the same values, especially around sexuality, gender, family, and those types of things; they don’t. They go in a different direction. For them the anti-colonial struggle is the backdrop.

John Wesley, [William] Wilberforce—the anti-slavery, anti-colonials struggles that are the early Methodists. So they are not down with postmodern culture and values in their church. And they are not going to be dictated by primarily white elites from the United States or England. They’re not going to do it. And so they will go their own way.

The same with the Episcopal Church. And all of these Protestant denominations. While they’re declining in the United States and the West, they’re growing in Africa. So you take the Episcopal Church, let us say in Uganda, or Nigeria or South Africa. They have said over the last 20 years that they do not want the cultural values of the American Episcopal Diocese. And they have threatened time and again to split off and go their own way. And so while Episcopalianism shrinks dramatically in the United States, it grows in Africa; but on Africa’s terms, and they won’t be dictated by westerners.

I just want to bring this to an end and then say a little bit about Baldwin on this question.

I am viewing the breakup of these mainline Protestant denominations with the larger crisis of legitimacy. Now, crises of legitimacy are generally articulated as political crises. And that’s the way we in the Free School have talked about this. Crisis of legitimacy—bourgeois political scientists’ framing of a problem of a crisis that Lenin called: the ruling class can’t rule in the old way and the people don’t want to want them to rule them anymore. That’s, you know, the same thing, different language, a little bit different clothing.

We’re faced with that in the United States. Crises of legitimacy in bourgeois, political context are manifestations of the fact—and this is from the poem The Second Coming, which I think we should all read all the time, by William Butler Yeats. Where he says, “The center will not hold. Things fall apart.” And so we have this in the United States—the center has not held. And thus can the ruling class govern if they cannot bring all sides, or most sides of the ruling elite together and under their leadership, the broad masses together with this idea of where we had an election, and now we’d be pragmatic and deal with the domestic and foreign policy, yada yada yada, you know.

But then the center has not held. And two sides at basic war with one another. And the thing that is so fascinating here in the United States is that the two sides, although not fully crystallized, are defined on the basis of the classes that make them up.

On the side of the Trump movement—and I’m not talking about the Republican Party—the Trump movement, which among other things is struggling to take over the Republican Party. The Trump movement, which has an anti-war wing. And we have to acknowledge that, and so on; it is the more working class of the two sides.

The white working class has completely left the Democratic Party. And Black workers are on their way to doing the same thing, which will undo the Democratic Party because Blacks are the most solid reliable base of the Democratic Party. I have estimated that close to 40% of Black men in this election will either vote for Trump or refuse to vote at all, as a conscious protest, both of them protest votes. The other side, the Democratic Party—when you do the numbers and the demographics—is the richest party, the most wealthy party, and made up of the richest, wealthiest people in history. There’s never been a party, since modern political parties have come into existence, that is such a party of wealth and frankly of war and austerity.

So you got these two sides. In some ways, although not in perfect form—and I want to say this—you know, the Left is always looking for some perfect manifestation, “Oh that’s not the class struggle.” Well the class struggle takes a lot of forms, and has many stages in its development. The class struggle in this moment might not look like the class struggle will look, let us say five years from now, or a year from now.

You know, interestingly, if this Colorado Supreme Court decision is allowed to go forward and they try it in other places, and they’re going to keep Trump off the ballot under some bogus interpretation of the 14th Amendment. Well, you’re stoking violence. Not that Trump has to call for it, but try to keep him off the ballot and see what people do. Because it will be not in defense of Trump, but in their anger at a ruling elite that would do something like this. It’s the same dynamic, politically and social psychologically, that we see with the breakup of these denominations.

I would argue that to the extent that there are working class and lower-middle class, non-elite elements, let’s say in the Unitarian Church and the Methodist Church—they have found it increasingly unacceptable to be ruled by elites. University-trained, et cetera. And we see this kind of, in our own interactions with the Unitarians. College professors, doctors, and so on and so forth, lawyers, professionals.

The same thing: the center will not hold in Methodism. The center has collapsed in the Unitarian, the center could not hold. In other words, after years and years of compromise, of discourse, of consensus-building, you reach a point where compromise is no longer possible. You know, like in a marriage—marriage is compromise all the time, we won’t get into that. But at some point, you can’t talk to each other. You don’t hear each other. You cannot compromise. Well it’s the same thing with these denominations. The compromise is no longer possible. And we have to go our separate ways.

Now Baldwin. No one that I know of, scholars on Christianity, Protestantism, I don’t think have brought to bear the deep insights of Baldwin. And I’m only repeating him when I say that Christianity is what frames American civilization. It is not, in and of itself, American civilization because American civilization consists of its political institutions, its cultural institutions, so on.

But I think the architecture of American civilization, of the deep values of Americans, of what Americans aspire to—at least what they say they aspire to—those values are to be found in American Protestantism.

But like Baldwin points out, the contradiction is [between] what is proclaimed—and what we aspire to, and how we live.

And if there’s nothing else about Baldwin, his studies of how the American people live.

And that contradiction of what we say and what we do. And of course, then the question of what we do with Black folk. And he is right, Baldwin is right.

That unresolved contradiction has brought us to where we are now. Now, Black Christianity ain’t doing that good either. I think for somewhat different reasons. I think the church, which about 40 or 50 years ago, the Black churches went—and they said it, it’s such a joke to think about it—went to a business model. You know, rather than a values model. Where everything becomes transactional, and we’ve experienced that, we won’t go into the details. That it’s all about the money. And what the Black churches were saying, “Look at these white churches in the suburbs. They’re doing good because they have a ‘business model.’” Well first of all hometown, you ain’t white. And you’re not in the suburbs. And that’s not your tradition. So the “business model” was your worst move, you know what I’m saying?

And so the further the Black church got into the business model, and then they went to megachurches and T.D. Jakes and this one and the other one and all that, and you know, well they had good music, I mean if you wanted to go to a free concert every Sunday, go to some of these megachurches. They sing the shit out of this Patti LaBelle-type singing, they just have religious lyrics. And that’s where they kept people, you know—great music. There was a split between traditional gospel, which also was a split off from the traditional sorrow songs and Negro spirituals. And then went to gospel; and then got into the 60s and 70s, they went into rhythm and blues.

I mean it was unusual. I don’t ever remember going to a church and seeing a band with electric guitars, electric bass, drums and all. I mean, it’d just be throwing down. So I mean, that was one thing that kept a lot of people coming to church as well. You know you can get dressed up, and if you’re looking for a partner, you know, all the handsome men, all the beautiful women are all dressed up and sexy and shit. And you know, a lot of churches became fashion shows. But that’s Black life. If you want, some Black exploitation films have explored this in a comedic way, and it is comedy.

But, they went to the business model and going to the business model meant that they also went to the politicians. And they also became, rather than critics of the state and its policies of discrimination and so on, of gentrification and all of this—they became allies of it in spite of the fact that their congregations, or what remained of their congregations, were becoming poorer and poorer. And so you only had the baby boomers and older people in walkers and shit and wheelchairs coming to church. And they were comfortable with this, you know.

And so they would survive often based upon their relationships with the government. For example, giving out free food. Another thing is having your church be a voting site, employing your members on Election Day.

But the very essence of Black Christianity was protest. Like Martin Luther, the founder of Protestantism—it was protest. And one of the interesting things: you know, Martin Luther King, that wasn’t his original name. His original name was Michael King Jr. And his father was Michael King Sr. His father went over to Germany, for some kind of religious conference, and he learned about Martin Luther. And that’s when he changed his name to Martin Luther King Sr., and Michael King Jr. was named Martin Luther King Jr. That’s how seriously they took protest. The Black church is not the Black church if it is not grounded in protest.

And this, here we go, “business model,” which is, I’ll put another way, a bullshit model. An anti-Black Christianity model, an entertainment model, a transaction; a person could have been a member of your church all of their lives and they die. And the family comes and says, “Well we’d like to have the funeral here.” And the preacher, the secretary of the church says, “Well here’s what it will cost you.” You say, “Well, but my mother paid into the church for 50 years, so we can’t, you know.” And therefore you get more Black people having their funerals in funeral homes rather than in churches. So the business model has eviscerated the soul of Black Christianity. And so Black people leave the church. But now Black people, unlike white people, have options. We have religious options that white people don’t have, it’s so interesting.

White people are lost, as they say “lost in the sauce, lost in the wilderness” you know, because they’re so bound to mainstream or mainline white denominations. And the operative problematic is white, which gets us back to Baldwin—hang on to that fiction, you will decline internally, externally. But anyway, Black people have options. One of the big options is the Nation of Islam, or Islam itself. In Philadelphia 40% of Black people, or more, identify as Muslims. You go around Philadelphia you get Black people all over with Muslim names: Jamal, Samir, Abdul. But it’s like Abdul Harris. It’s not like a Muslim name all the way down the line. It’s Abdul Johnson, you see what I’m saying?

But if the church, the Christian church don’t do what we need it to do, we will go to the Nation of Islam, or we will find a masjid—you know, Black people—because, our Islam is from Turkey, is from Pakistan, is from Saudi Arabia; it’s our own thing as we invented. So sometimes it’s called the mosque, other times it’s the masjid. Because Black people have that flair for the poetic, “masjid,” “I’m going to the masjid.” You know, it has that kind of swag to it. Or you can be a Five Percent Muslim, a follower of Clarence 13X. Or you can go mainstream and try to go into a regular mosque, a South Asian mosque, Sudanese—you know what I’m saying. Or your mosque could be called a temple. But anyway we have that option.

And so the Muslims will say, “See we told y’all, you should never have followed the white man’s religion. That’s a slave religion, so come on over here where you belong anyway.” That’s the way Black people can talk and think, very interesting. White people don’t have that option; they’ve shut themselves off from all of this. You don’t want to be Muslim, you don’t want to be nothing but white. So be that until the wheels come off. Like they said, “I’m gonna ride this white thing out and see where it takes me.” Well it’s done drove you into a brick wall, now what are you gonna do?

Well, you know what Baldwin’s option is: give up whiteness. Become the last white nation.

Then, Black people have another option: African spirituality. Akan, Yoruba, you know, all different—or we can synthesize, we can be a Yoruba and an Akan. I mean, it’s a beautiful thing to see. And then if that ain’t good enough, you can do like a lot of jazz musicians—“I’ve become a Buddhist, and I chant the Buddhist prayer.” And if that ain’t enough, you can do like Alice and John Coltrane did—“I’ve become a Hindu.”

Because, see, Black people are not inhibited by whiteness. The world has all of these possibilities. We don’t have to go Christian or white, we can go any of these things. And this is why the crisis of Black Christianity, and it is a crisis, has not closed off the possibilities of religion and spirituality. And like Farrakhan says, and if you go to the Nation of Islam you can see it, they are better Christians than the Christians. They even say, “We’re better Jews than the Jews.”

The Black thing is just so fascinating. But anyway, what is the answer for the American people for whom religion and Christianity, Protestantism in particular has failed them? It is to return to the roots of the Third American Revolution on the pathway to the next American Revolution. And that is Martin Luther King.

That theology holds up better than any theological framing. In some ways superseding Martin Luther [of Germany]. King was both rationalist theology—Paul Tillich, Reinhold Niebhur—and the spiritualism of the African.

King’s interrogations of time, his idea of a cosmic companionship. You can go to West Africa among the Dogon people, and that will resonate, that idea of a cosmic companionship. An infinitude beyond time.

King protested the church being taken over for monetary and material reasons. So it will be King, and it will be Baldwin.

This is a deep crisis. Unless you understand this country and its people, you can’t understand this crisis. If you have a point of view that says that religion is the opiate of the people, rather than the cry of the people for something more; if you see religion and its Protestant American form as not aspirational, but as a negative response—if that’s all you see, you’ll never understand the American people. If you want to reduce, as most, and I put quotes here, “mechanistic materialist” and “mechanistic Marxists” do—“that’s trivial, that’s unimportant,” “those values are the result of a people who are not class conscious” and all of that shit—if that’s the way you want to do it, well you will be the recipients of the utter contempt of the people. People respect their moral and spiritual religious values, no matter what we think of them.

So we’re on the cusp of something very new. Possibilities abound. And I would just like to suggest three articles, two of which I got and I really want to thank Emily for this. And they’re in the text The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings of James Baldwin. And it’s so interesting that there are still uncollected writings of James Baldwin.

The first essay is “We Can Change the Country.” The other is “To Crush the Serpent,” which was his last essay. And “On Being White And Other Lies.”

I would suggest that Baldwin is a great American revolutionary theorist. That no American revolutionary, who was really honest about what we’re trying to do, can go forward without Baldwin.

Leave a comment