Since the 2016 election and the launch of the 1619 Project, Gerald Horne, a professor at the University of Houston, has emerged as a prominent analyst of race and left-wing politics. However, despite his background in the Communist Party USA and his prolific writings on Black communists, he is purveying a new form of nationalism in left-wing garb that serves the U.S. ruling elite in a time of crisis. Among the ways he has done this is through his 2014 work The Counter-Revolution of 1776, which is a direct inspiration for the 1619 Project, as well as articles and podcasts commenting on W.E.B. Du Bois and the post-2016 political situation in the U.S.

Empiricism and Horne’s Fundamental Misunderstanding of Black Reconstruction

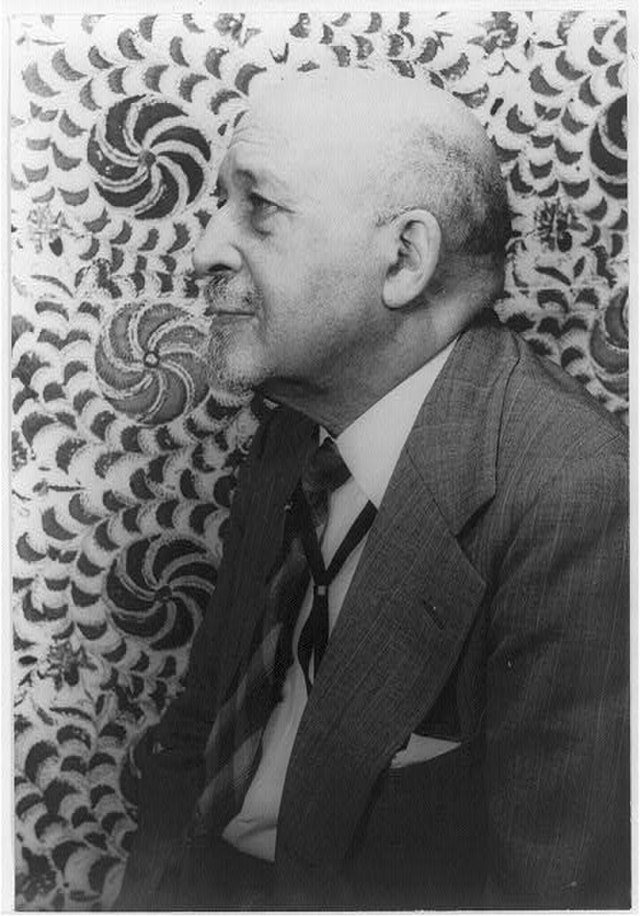

Let us begin however with his engagement with Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America. Horne has been tapped by sections of academia and the establishment media to use his expertise on race and left-wing history to explain the current political crisis. One example of this is an essay by Horne in The Nation magazine in Spring 2022 entitled, “Abolition Democracy: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Making of Black Reconstruction.”

A closer look at Horne’s methods reveals a heavy reliance on empiricism, the philosophical worldview that is largely an assumption in the American historical profession. Empiricism is an approach that holds that facts and data alone are sufficient to understand the world. It largely believes that thinking through broader categories is not needed to connect these facts into an understanding of the truth.

The essay reduces Du Bois’s contributions into merely challenging the racist Dunning School view of history, which held that Reconstruction was a failure because of the inherent inability of Black people to govern. This is the meager recognition academia pays to Du Bois. Though Horne adds words about Du Bois merging Marxism and race analysis, his overall framing serves to turn Black Reconstruction into an empiricist history like the ones Horne writes.

Attempting to apply an empiricist standard, Horne goes on to critique Du Bois for his “glaring omissions”—chief among them the failure to confront the “indigenous question.” He goes on to say that Du Bois could have performed an immense service if he had looked at Reconstruction through the lens of “settler colonialism,” as opposed to grouping the American republic with the French Revolution or the transformative Haitian Revolution. Sadly—according to Horne—Du Bois was not in the vanguard of reimagining the U.S. as a “prison house of nations” quashing self-determination for all but the “settler class.”

This brings us to the real crux of the issue. Firstly, Horne fails to see that Black Reconstruction is not just trying to capture all the empirical facts about the Reconstruction era. Horne fails to see that Du Bois’s concept of the “Black Worker” is not an empiricist description of a racial or class grouping, but a scientific category. The “Black Worker” concept is both concrete and universal, both the black working class and the whole working class. It is not special because it describes an aggrieved group, but because it identifies the revolutionary agent during the Civil War and Reconstruction, as well as the revolutionary capacity of the working class up to our times. Du Bois pushes for a higher form of dialectical materialism that uses categories like the Black Worker, the White Worker, and the Planter as dynamic forces, whereas Horne lapses into a mechanical materialism that sees race and class as static categories.

Central to the Black Worker for Du Bois is the struggle for democracy. Far from being a “settler nation,” Du Bois sees America as existentially tied to the Black Worker, whether the U.S. racist elite admit it or not, and the fate of the Black Worker as central to the problem of democracy in America. Black Reconstruction is not only empirical history, but sociology and philosophy in the study of the revolutionary process to understand its logics in the U.S.

As Du Bois writes:

“Here is the real modern labor problem. Here is the kernel of the problem of Religion and Democracy, of Humanity. Words and futile gestures avail nothing. Out of the exploitation of the dark proletariat comes the Surplus Value filched from human beasts which, in cultured lands, the Machine and harnessed Power veil and conceal. The emancipation of man is the emancipation of labor and the emancipation of labor is the freeing of that basic majority of workers who are yellow, brown and black.”

Du Bois’s Black Worker is central to the struggle for labor, religion, democracy, and humanity. The exploitation of the Black Worker is central to the origin of the modern world epoch. The real freedom of man is the freedom of labor, and real freedom for all labor is the freedom of the darker workers of the world in the U.S., Africa, and Asia.

Counter-Revolution of 1776: Rejection of Principled Unity, Skin Strategy, Belief in the Ruling Class over the People – A Rejection of Revolution in America

Though Horne has written many books piecing together historical data, his 2014 work The Counter-Revolution of 1776 has received special attention as a major inspiration of The New York Times’ 1619 Project. The book’s thesis is that the American Revolution was a war by the patriots to prevent the British Empire from abolishing slavery. This has come under serious allegations of misuse of data, including the twisting of primary source texts to support his thesis. These allegations have not been responded to by Horne.

Horne’s thesis and its implications obscure Du Bois’s approach to history. It removes the question of democracy from the struggle in the U.S. It leaves no possibility of the Black Worker struggling to reconstruct democracy in America. In a “prison house of nations,” the struggle for full citizenship by the Black Worker and its radical possibilities is futile. Casting all white Americans as a “settler class” is entirely different from Du Bois’s sophisticated study of the “White Worker” and the challenges of the White Worker rising to the level of the Black Worker to form a revolutionary U.S. working class. Du Bois’s other concepts—such as abolition democracy, the dictatorship of the Black Proletariat, and the demise of Black Reconstruction via the “Counter-Revolution of Property”—are also obscured by the settler thesis. Overall it is an argument that the working class as a whole is hopelessly backward, and this nation unworthy of revolution.

This is seen in his argument in the preface of the book:

“I am tempted to conclude that the older radical slogan—‘black and white, unite and fight’—as a prescription for transformative change in this republic needs to be supplemented (or supplanted altogether) in favor of a less poetic and catchy ‘Africans here and abroad unite and fight in league with a powerful foreign ally.’” (xii)

Horne states that his research leads him to skepticism about the traditional Marxist-Leninist view of interracial class unity. In contrast to Du Bois’s project of advancing the dialectical materialist understanding of race and class to struggle for a new American democracy, Horne retreats from the revolutionary position to revert to a cultural nationalist one more akin to Marcus Garvey.

His arguments about the world situation are based on a similar logic:

“Even then I was wondering if China’s rise would have a positive impact on the dire plight of my ebony compatriots in North America, just as Spain had centuries earlier.” (xiii)

Horne believes cynically in the slogan, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” as opposed to principled internationalism. He equates the Soviet Union and People’s Republic of China with Spanish and British imperialism, since all are enemies of the United States.

Neo-Cultural Nationalism: The Implications of the Settler Colonialism Thesis Today

The settler thesis is convenient to the U.S. ruling elite, which is losing control over historic sections of white America—what Du Bois would consider the White Worker. Yet the settler thesis, rather than raising the struggle for democracy as Du Bois would, assists the elites by painting any anti-elite movement of the white masses as “fascist.” This is what The New York Times, MSNBC, and Joe Biden are turning to in the face of the populist (and increasingly multiracial) Trump movement. Horne is a major source of elite stabilization through The New York Times’ 1619 Project, telling Black folk, in particular, that their only allies are the woke elite behind the Democratic Party.

Horne approves of these media outlets—which have never held anyone accountable for promoting criminal U.S. interventions in countries like Iraq and Libya—as racially more progressive than most of the U.S. Left for accepting the settler thesis. In another essay he argues for Black America to engage in an anti-Trump alliance with a woke elite and nihilistically gestures to a foreign ally to take the place of the British or Spanish Empires in previous periods. This is again the notion of the working class, as a whole, being backward due to a majority of it being settlers and therefore inevitably fascist.

Horne’s argument plays a reactionary role in our times. He believes the ruling class is the enlightened party, and he is signaling to Black people and others concerned with racism that the ruling class is their friend. He is defending the ruling class at the very moment that the American masses are losing faith in the ruling class.

Since Horne is so focused on “destruction” rather than the democratic remaking of the nation as the goal of revolutionary Black politics, he does not take seriously the task of opposing the Biden administration’s war policies via building a formidable peace movement. On the Decolonial Buffalo podcast, Horne said that the outbreak of World War III due to the Russia-Ukraine War would have “good and bad consequences.” The good would be that the U.S. elite would somehow be forced to negotiate terms with the leadership of Black America, analogous to the Rhodesia Lancaster House talks in southern Africa.

All of this shows that the settler thesis is un-Du Boisian; therefore, Horne deploying it in his review of Black Reconstruction shows his fundamental opposition to the work. It being the basis of his Counter-Revolution of 1776, his other books, and the politics pursued by him and his colleagues shows their fundamental opposition to the Du Boisian understanding of race, class, and democracy in America.

The Crisis of Neocolonialism and the Way Forward

Horne often provides analysis on world events and sees himself as an internationalist, but he reveals an attitude that is hopeless about the political struggle in the U.S. moving forward. This is contradictory because the crisis of neocolonialism, which we are seeing in places like West Africa, is fundamentally tied to the crisis of the U.S. state, manifested in the populist Trump movement’s challenge to the U.S. elite consensus. Horne’s work provides ammunition to initiatives such as the 1619 Project to essentially reinscribe the color line in U.S. politics, in order to hamper the possibility of a multiracial working class struggle that can fulfill the vision of the Black Freedom Struggle.

This is why we should characterize Horne as purveying a neo-cultural nationalism, despite his past in the CPUSA and his claiming to follow in the legacy of Du Bois. Horne embodies a more sophisticated version of what Henry Winston in the 1970s called “Neo-Pan-Africanism.” This ideology, embraced by ultra-radicals and Black capitalists alike, put forward a “suicidal skin strategy” misconstruing Du Bois’s revolutionary Pan-Africanism to argue for an unprincipled notion of racial solidarity.

Claiming the legacy of Du Bois and other freedom fighters, it has more in common with the anti-revolutionary politics of Marcus Garvey. This way of thinking uses a reductionist understanding of race to obstruct Du Bois’s sophisticated understanding of class struggle. Where thinkers like Winston, Du Bois, and King had developed understandings of race and class that were dynamic and worked for principled unity among the masses to struggle against the racist elites, Horne’s definition rejects the possibility of not just principled unity but also, like Garvey, revolutionary struggle itself. This is preached by Horne at a time in which the wages of whiteness are paying less than ever, when the working class as a whole has gone through a shared experience of deindustrialization and despair, and there is rising sense of the illegitimacy of the elites and the state apparatus.

The vision of freedom fighters like Du Bois, Winston, and King is incomplete, but their sacrifice has impacted the consciousness of the people, meaning that racism among the masses in 2023 is nothing like in 1963.

Horne’s thesis, bolstered by The New York Times and others, is an attempt to reinscribe the color line at the very moment that it, along with the system as a whole, is in deep crisis. Though Horne dons the guise of anti-colonialism, especially in Africa, his neo-cultural nationalism assists the state in fulfilling its policy, outlined in National Security Memorandum 46, of dividing the Black Freedom Struggle from the liberation forces in Africa. A serious understanding of neocolonialism means that we in the U.S. cannot afford to adopt pessimism, to surrender our belief that the American people can commit the highest act of international solidarity in confronting their own ruling class.

Where the radical Horne is pessimistic about the American people challenging their elites, ruling class ideologues such as Richard Haass are ringing alarm bells that the American people themselves are the greatest challenge to the U.S. elites’ conception of “Democracy,” even more than Russia or China. The imperialist Haass is realistic in understanding the crisis of U.S. “Democracy.”

The real answer to the crisis of neocolonialism is to return to Du Bois and Black Reconstruction. Ninety some years after its publication, revolutionaries in the U.S. have only begun to understand its profound implications for the struggle for a new nation. We must reject those, like Horne or other academics, who seek to minimize Du Bois toward agendas suitable to the ruling class. We must do the difficult work of understanding Du Bois on his own terms and the revolutionary history, philosophy, and sociology he presents in this study of Reconstruction.

The issue is not whether the Founding Fathers are the great icons of today or whether the American Revolution is foundational for revolution today. The issue is whether the American people are capable of waging a revolutionary struggle today. American history has progressed through two successive and more radical revolutions—Civil War and Reconstruction as a Second Revolution, followed by the Civil Rights Movement as a Third Revolution which dramatically addressed the contradictions of the Revolution of 1776 and pushed forward a more complete human vision. We are in a radical period which provides an opportunity for a Fourth Revolution.

Leave a comment