At a time when Americans and especially young people are searching for an ideological alternative to the ruling elite, Norman Finkelstein’s new book I’ll Burn That Bridge When I Get To It! offers much in the way of cynicism and little in the way of answers. Wading into “culture war” issues of cancel culture and identity politics, Finkelstein remains trapped in a perpetual state of reaction to woke elites—and in sinking to their level, he proves unable to provide moral or political clarity to those who may earnestly look to him for it.

This article will approach Finkelstein’s book on three fronts: his usage of historical figures in service of broader ideological arguments, his analysis of the contemporary political landscape, and the general project of the book itself. It goes without saying that this article is not written as an attempt to cancel the author—it is intended as an honest critique, with a bit of polemic mixed in. These are forms of discourse that Finkelstein himself embraces.

Rejecting “Ideology”

When trying to get a sense of Finkelstein’s ideological make-up, a good place to start is at the end of Burn That Bridge, with the book’s index. Among those he mentions primarily in a positive light, Finkelstein cites or refers to W.E.B. Du Bois more than any other person, at 37 times. Martin Luther King Jr. is next, at 27. John Stuart Mill rounds out the top three, at 24.

The list goes on: Frederick Douglass, 20. Paul Robeson, 19. Bernie Sanders, 19. Leon Trotsky, 15. Bertrand Russell, 12. Noam Chomsky, eight. Vladimir Lenin, six. Rosa Luxemburg, five.

It is indeed remarkable that the book elevates, at least in quantitative terms, some of the greatest American figures of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—Du Bois, King, Douglass, and Robeson. But what are they doing together with John Stuart Mill, Bernie Sanders, Leon Trotsky, and Bertrand Russell?

This is not a facetious question. A mix of different influences can be a sign of robust eclecticism. Yet if no clear attempt is made to connect these influences, the reader can only assume incoherence or obfuscation on the part of the author. Finkelstein comes across as guilty of both.

As he has recounted on numerous occasions, Finkelstein was a devoted Maoist in his youth. Upon hearing news of the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1976, he had a mental breakdown. He renounced Maoism and the Chinese Revolution; in the years following, he became a devoted follower of self-described libertarian socialist/anarcho-syndicalist Noam Chomsky. Of his Maoist phase, Finkelstein writes in the book: “The most bewildering thing about Maoism was, you never knew when the Party Line would change or why. One day’s ‘true disciple’ of Chairman Mao would be denounced the next day as a ‘running dog of U.S. imperialism.’ Today’s woke politics is yesterday’s Maoism come alive. This epithet is politically correct; that epithet is verboten.”

The comparison of American Maoism to contemporary wokeness is a fair one. But there is a deeper undercurrent in Finkelstein’s attitude toward the dogmatism of his Maoist youth that is left unsaid—Finkelstein appears to have rejected ideology altogether. So thoroughly disappointed by his own perception of Maoism and its failures, Finkelstein rejects the basic need to commit himself to a coherent set of ideas by which to fight for the future.

In the absence of a forward-looking outlook, Finkelstein frequently gestures to radical thinkers yet defaults to a hodgepodge of retrograde philosophies that are inadequate for addressing the full scope of today’s crisis, whether that be classical liberalism as personified by J.S. Mill or the static analytic philosophy of Bertrand Russell. As such, in Finkelstein’s worldview there is little sense of the historical movement of ideas. Instead there are only opinions, arguments, facts, etc. to be volleyed back and forth in an endless debating circle. It is as if some part of Finkelstein has meekly acquiesced to the “end of history” thesis that announced the triumph of Western liberalism, even as another part of him clings to the memory of his radical youth.

A clearer picture emerges in Finkelstein’s treatment of W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. Both figures were titans of thought; not only courageous revolutionaries, but pioneers of philosophy, social science, history, and the study of human civilization. Yet Finkelstein effectively relegates them to serve as mere foils to a slew of ideologues whom he attacks in his book. Here, Robeson only matters insofar as he stands as a counter example to the preening selfishness of today’s woke activists; Du Bois only matters because his rigorous scholarship contrasts with the laughable pseudo-intellectualism of Ibram X. Kendi. Finkelstein refuses to look directly at the ideological contributions of Du Bois and Robeson themselves. Why?

During a chapter on Ibram X. Kendi, Finkelstein examines monumental works by Du Bois such as The Philadelphia Negro and Black Reconstruction in America. He writes:

“What stands in relief in Du Bois, as both scholar and personality, is his utter fearlessness and inner calm in the face of Truth. It always helps, never hinders; he is ever patient with it, never fazed by it; if an egregious practice be discovered among Black people, it can be rationally accounted for, without diminishing Black humanity. Consider, by way of illustration, his treatment of corruption during Reconstruction… Du Bois doesn’t deny that corruption was rife; on the contrary, he keeps returning to it in excruciating detail. However, he situates and analyzes this phenomenon from multiple angles.”

Clearly, Finkelstein respects Du Bois. Yet this is the furthest extent to which he can understand Du Bois—as a scholar committed to empirical truth. Du Bois is perhaps the most important thinker for our time; for this reason, he is being appropriated left and right by bad faith actors seeking to distort his legacy. It is therefore even more crucial that the totality of Du Bois should be presented to the younger generation. In that regard, Finkelstein fails. He offers only a narrow picture of Du Bois—a reflection of the kind of meticulous scholar Finkelstein aspires to be. The Du Bois who introduced new ways of thinking about the logic of revolutionary change in the United States in works like Black Reconstruction—and who proclaimed himself as both a scientist and a propagandist for freedom—is too large to fit into Finkelstein’s imaginary.

In the first chapter of the book, Finkelstein positions Robeson similarly against the identity politics of today: “Paul Robeson, who had one foot firmly planted in the African-American struggle and the other in the international struggle of the working class, finessed the seeming contradiction by proclaiming that each facet of his bifurcated identity enhanced the other.” Finkelstein makes no attempt to tease out the “seeming contradiction” of Robeson’s conviction; he can only gesture to its complexity. Consequently, he struggles to draw the connection between the Black experience and his own Jewish heritage—lumping them both under the label of racial/ethnic “identities.”

What Finkelstein cannot understand is the essence of what Robeson and Du Bois theorized and represented in action: that the Black proletariat’s struggle for freedom is the American class struggle in its becoming. In other words, the striving of Black folk to become a free, conscious people for themselves provides the basis for the entire working class to strive to become a free, conscious class for itself—and thus a force for humanity. At critical moments in our history, the search for self-realization by African Americans has reconstituted the basic foundations of the American people’s consciousness. No other group can claim this historic role—even as this history becomes our universal birthright, laying the groundwork for a new American civilization.

One can infer that Finkelstein does not follow these threads because they would lead to conclusions that clash with his worldview. It is for this reason that he minimizes the main ideological content of Black Reconstruction, even as he cites the work frequently. Finkelstein ultimately prefers to pick and choose ideological sources as he pleases, without claiming the responsibility that would come with identifying substantially with any one of them.

So when he needs to frame the grounds for democratic discourse, Finkelstein goes to Mill and Russell. When he needs an example of how to conduct revolutionary politics, he turns to Lenin, Trotsky, or Luxemburg. When he needs to raise the “class question,” he goes to Bernie Sanders. It is usually only when Finkelstein needs counterweights on questions of racial identity, African American history, and the Black intelligentsia, that he brings in Du Bois, Robeson, Douglass, and King—not seeing that these figures could provide insights on all of the above. Ironically, in his attack on identity politics, Finkelstein upholds his own de facto racial division between ideas that are suitable for invoking the authority of Black thinkers, and those that are not.

Avoiding Reality

Part I of Finkelstein’s book reads as a series of polemics upon a collection of ideologues who have weaponized identity politics and cancel culture: Kimberlé Crenshaw, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ibram X. Kendi, Robin DiAngelo, and Barack Obama. Many of the criticisms land; none of these woke icons are morally defensible or logically coherent by any means. If anything, Finkelstein tends to take these figures too often at face value, parrying each of their claims with an extensive debunking that may miss or obscure the deeper agenda at hand.

Consider the case of Kendi, recently embroiled in scandal with his multi-million dollar “antiracist center” at Boston University firing half its staff and coming under investigation. Finkelstein wastes no breath excoriating Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist as devoid of intellectual content. He rightly denounces Kendi’s work as an attack on genuine anti-racist scholarship and the legacies of those like Du Bois and Martin Luther King who struggled to overcome racism. However, the truly remarkable story at the heart of Kendi’s precipitous rise (and now apparent fall) lies in examining the forces that promoted his vacuous book in the first place.

Finkelstein attributes the rise of identity politics and woke ideology to the Democratic Party and billionaires like former Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, who pumped $10 million into the Kendi brand. But Finkelstein treats these as independent actors, when they must be seen as figureheads of the state itself—that set of institutions and relationships underpinning the rule of the ruling elite. The great lesson to be gleaned from Ibram Kendi, or the general phenomenon of wokeness, is in understanding the strategy of the ruling class at a particular juncture in U.S. history. Finkelstein grazes these currents but fails to grasp them; it is as if he is so transfixed by the fluttering red flag of Kendi’s stupidity that he cannot fully comprehend the hand that is waving it.

As Finkelstein notes, the Democratic Party systematically abandoned its mass base of trade unions and the working class in favor of the super-rich and oppressed minorities “of every imaginable ilk—ethnic, sexual, whatever.” Who stands in the way of this transformation? For Finkelstein, it is Bernie Sanders. Indeed, Part I of Burn That Bridge is as much about Sanders as it is about the titular characters lambasted in each chapter. Finkelstein argues that the driving animus behind cancel culture has been the mainstream media’s desire to discredit Sanders, whom he lionizes as the lone champion of a “working-class agenda” in national politics.

That the Bernie movement emerged in 2016 as part of a larger anti-establishment awakening cannot be disputed. The other wing of this awakening, of course, was the Trump phenomenon. What remains in 2023? The Trump movement has grown and evolved, becoming more hard-edged, more animated against the American state apparatus than ever before. Bernie Sanders, meanwhile, has become an embarrassment—a sad meme of a figure who essentially serves as a lapdog of war and part of Joe Biden’s campaign staff. Trump has become an enemy of the establishment; Sanders has become the establishment.

Finkelstein, tellingly, does not comment on Sanders’s capitulations to the Democratic Party in the book (more recently, he has criticized Sanders for his support of Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza). Finkelstein opts for the safer narrative—that Sanders was undermined by the powers that be; and that these attacks on Bernie-style progressive politics have created a vacuum for Trump to assert his own toxic “right-wing authoritarianism.” But what if Donald Trump represents something else entirely?

Only the ideas of a thinker like Du Bois could show that the Trump movement constitutes a historic rupture in the paradigm of white supremacy and its grip on the white working class. While Finkelstein and Bernie-allied historian Eric Foner have espoused the idea that Trump supporters are akin to the Ku Klux Klan 2.0, Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction points in the opposite direction of this notion. White supremacy was pounded into American social life and ideology in the service of a growing imperialism; Trump, for all his faults and weaknesses, functions as a vessel of the people toward imperial retreat and as a blunt-force weapon against the state. Trump is thus a far greater threat to the ruling elite than Sanders ever could be.

It is against this threat that the ruling elite latched onto wokeness as an attempt to reinscribe the color line. A case in point: today, young progressive people are overwhelmingly against funding Israel, while the Trump movement is overwhelmingly against funding Ukraine—and the Black community is skeptical of both wars. Wokeness—both in its deployment and in the reaction against it—functions to divide these movements. Moreover, wokeness puts up a mirage that works to prevent Americans from seeing the Black tradition as the clearest throughline to a coherent, unified anti-war movement.

To miss the entire arc of these developments is to misread other questions as well. Finkelstein writes of the summer of 2020:

“It also couldn’t but be happily noticed by this gray-haired protester during the George Floyd demonstrations, the naturalness with which white and nonwhite millennials commingled, and the sincere outrage of white youth at racist cops. In the heyday of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, white support was awkwardly tinged with noblesse oblige or radical posturing. The ease noticeable nowadays owes not just to the enlightened zeitgeist, but additionally to the fact that white youth have also come to be marginalized by the economy, joining the ranks of the superfluous hitherto filled by those of darker hues, while many have found themselves, crammed four to an apartment, rooming with a motley humanity. […]

The white demonstrators were almost to the last former Bernie Sanders supporters. Those who earlier attended the Bernie mega-rallies were now marching in the streets. Youth supported Bernie because his agenda spoke to them: Medicare for All, free higher education, cancellation of student debt, massive public works/jobs programs, and combatting climate change.”

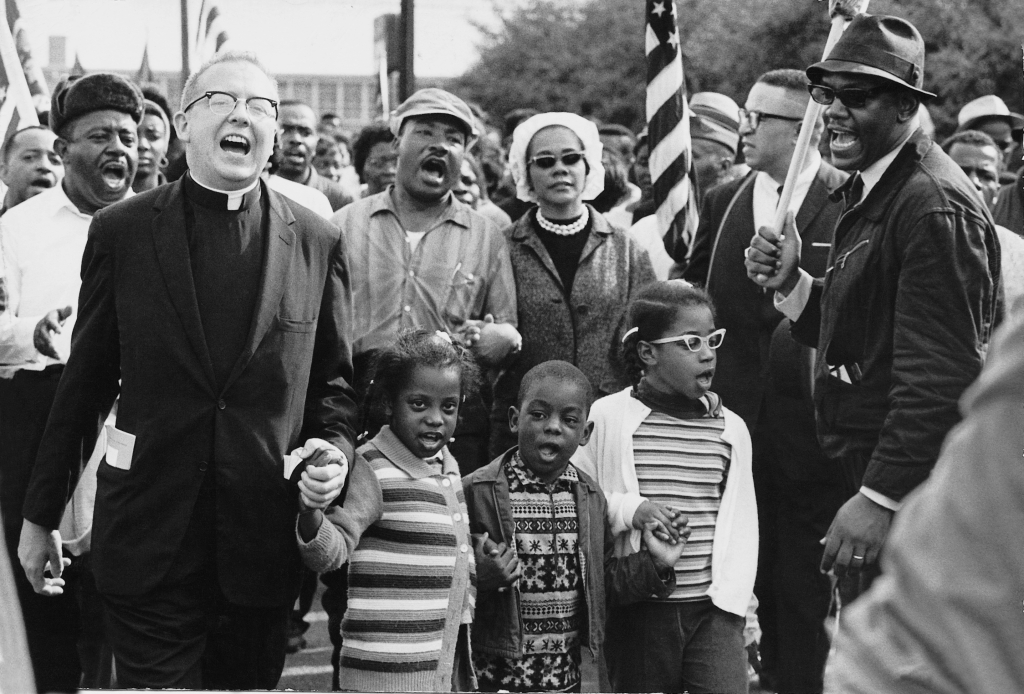

Were all instances of white participation in the Civil Rights Movement—including martyrs like James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo or freedom fighters like Carl and Anne Braden—tinged with “noblesse oblige or radical posturing,” or is Finkelstein speaking more for himself? And is Bernie Sanders really the most potent symbol of young people’s aspirations?

The George Floyd protests were, per Finkelstein’s own accounting, a conflagration of public anger that quickly became a vehicle for Joe Biden’s election hopes, an upsurge in community violence, and the most absurd formations of faux-radical sloganeering and collective guilt tripping yet seen in the American landscape. The Civil Rights Movement, on the other hand, was a revolution that overturned a regime of segregation, forced an end to an imperialist war, forged new social relations and unity among disparate communities, and sought to fulfill and redefine the promise of democracy on terms set by the American people. It did so armed with iron discipline, uncommon courage, and the people’s own creative genius. It left us with the unfinished task of achieving a new people’s democracy over the ruins of imperialism.

Even as he defends the Civil Rights Movement against the likes of Kendi, Finkelstein diminishes its legacy by insisting that the logical successor to the Black Freedom Struggle is the Bernie movement. Finkelstein further writes that “racism is real, its invidious effects are real; the plight of African-Americans does not reduce to class oppression”; the unspoken corollary of this is that he fails to recognize the Black Freedom Struggle as the American articulation of class struggle. He argues that nonviolence sought to facilitate “a genuine moral recognition by whites of the special burdens deposited by history on the backs of Black people.” But nonviolent struggle was not simply a matter of making whites sympathetic toward Black people; it compelled white people to confront their own state of spiritual debasement and infantile ideology as a consequence of white supremacy. One would expect Finkelstein, who has spent years researching and writing about Gandhian nonviolence, to know better.

By downplaying the significance of this history, Finkelstein does a grave disservice to young people today—because it is precisely our generation’s task to meet and go beyond the great sacrifices and achievements of our forebears. Herein lies the difference between class struggle as an abstract notion, versus class and people’s struggle as a concrete universal.

Scorning Humanity

Finally, we approach the totality and tenor of the book itself. It is an endeavor that requires, for the purposes of this article, a bit of personal context.

I first encountered Norman Finkelstein as many have: as a college student who came to admire his staunch defiance against the academic and media establishment. I watched YouTube videos in which he deftly countered the crocodile tears of Zionists seeking to discredit his research on Israel’s mistreatment of the Palestinians and the misuses of the Holocaust to justify said mistreatment. During one winter break, I traveled to Philadelphia to hear Finkelstein speak at an event hosted by the Saturday Free School concerning the horrific conditions of the Gaza Strip under economic blockade.

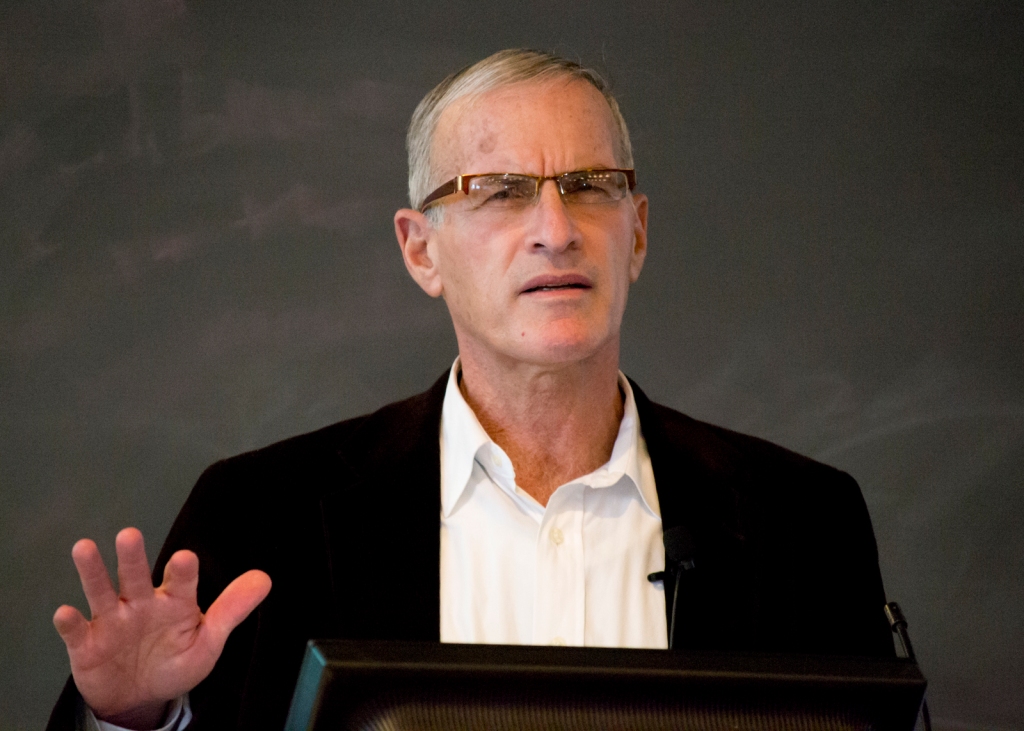

My next encounter with Finkelstein came a few years later, immediately prior to the publication of Burn That Bridge. By that time, Finkelstein’s star had risen significantly higher in online leftist and anti-establishment circles. After hearing him speak at the launch event of Sublation Media, the publisher of his book, I happened to run into Finkelstein in the subway going home. We struck up a conversation; upon hearing that I had majored in English, he asked if I might be interested in proofreading his manuscript. I said I would consider it.

After some back and forth and reading a few early chapters, I eventually declined—mostly due to the length of the book and my own limited capabilities. Though I did have a chance to give some feedback; I told him I disagreed about his characterization of the George Floyd protests, but that I enjoyed his chapters on Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X. Kendi, since the latter chapter engaged with Du Bois.

Looking back, I was likely a bit starstruck upon meeting Finkelstein and over-eager to please. Parts of Burn That Bridge are satisfying, in the way that “Marxist Professor Destroys Woke Liberal”-type viral videos can be satisfying. But my overwhelming feeling upon reading the whole book—a sentiment I didn’t voice forthrightly, to my regret—is one of unease.

In chapter after chapter, Finkelstein douses the reader with gallons of his disdain. No doubt, the ruling elite and their chattering class of propagandists are worthy of contempt, as he writes in the preface. But what happens when contempt consumes you?

Let us leave aside for a moment the legalistic rules and exceptions to free expression. It does not take a puritanical sensibility to be thrown off guard by an anecdote in which Finkelstein—daring the reader to be offended—recalls joking to a young female staffer at Democracy Now, “You look so young, you could be one of Michael Jackson’s playmates.” Neither does it require an ultra-woke mentality to be disturbed by numerous drawn-out paragraphs where the author brazenly parrots Black Ebonics, presumably to give his mocking parody of Robin DiAngelo a more controversial bite. It is a bizarre, flatly offensive “comedic” choice.

Then there is Finkelstein’s treatment of Angela Davis. Despite his claims that it brings him no joy to do so, Finkelstein exudes a tangible sense of relish in his take-down of the former Communist Party member and icon of the Black Freedom Struggle. He reduces her life to a tasteless punchline: “Enter Angela Davis. Once upon a time she was on the F.B.I.’s Ten Most Wanted List. Now she’s on Martha’s Vineyard’s Five Most Coveted List.”

No figure should be above criticism—and Davis’s transformation from a brilliant communist polymath and lightning rod of international solidarity, to a celebrity trotted out at universities and fundraisers for radical-sounding isms is indeed tragic. But it takes a sense of humanity to convey human tragedy.

Finkelstein, whose stated youthful admiration for Angela Davis is undercut by the actual history of Maoists derailing the very same broad coalitions that supported Davis’s freedom, lacks the empathy and moral authority to make his critique seem like anything other than bitter, gleeful, ad hominem attack. If the reader is looking to learn something from Angela Davis’s life, in both a positive and negative sense, they will not find it here. And what of the reader who goes to Finkelstein, in general, looking for answers from a veteran of the Left?

Like many, I was drawn to Norman Finkelstein because I thought of him as a principled person. I came away feeling disappointed. Finkelstein is a public intellectual; he appeals to a generation of young, disaffected leftists who rightfully distrust narratives that emanate from the ruling class. He thus bears a responsibility to the younger generation, whether he likes it or not. Rather than honor this responsibility, Finkelstein runs away from it—not overtly, but through the ugliness and unseriousness that surface during his fits of condemnation and his failure to present a meaningful alternative.

Finkelstein has taken an important stance against Zionism as an American Jew. This is especially relevant today, when young people see him as an authority on the Israel-Palestine conflict and many young Jews are questioning the ideology they have been raised on. However, Zionism must ultimately be situated in relation to both white supremacy and colonialism. If one goes by this book, Finkelstein does not display a clear understanding of the color line in America nor as a global phenomenon. Neither can he bring himself to recognize the Palestinian resistance as an expression of the world anti-colonial movement—likening Hamas’s October 7th offensive to a slave revolt, rather than something akin to the Tet Offensive. Perhaps drawing such a connection would evoke too many memories of his Maoist days. Nevertheless, it is the freedom struggles of the 20th century which must be acknowledged for giving rise to the seismic continental changes we see today.

What are the larger lessons to be drawn from this? Simply being anti-woke is not an ideology, nor is it a real response to wokeness; it is only a reaction. When we adopt a permanent attitude of scorn and cynicism, we are in fact capitulating to the ruling elite. We grow increasingly distant and isolated from humanity and thus nip our own human potential in the bud. We succumb to a juvenile, smirking, self-satisfied identity that decries everything yet claims responsibility for nothing. Far beyond the paper-thin constructs of an Ibram X. Kendi or a Robin DiAngelo, these are the real vestiges of whiteness—as an ideological and psychological disposition that separates us from the world of reality, in all its vast and almost inconceivable changes.

Some voices fade with time; others ring truer and more urgently through the force of history. Du Bois, King, Robeson, Douglass—these are figures who provide an example for how to live, shouldering responsibility out of a love for humanity. Their voices are a touchstone for young people today to make sense of America’s complex history, the meaning of race and white supremacy, and existential problems of identity and political purpose. Such questions have long been determined and bastardized by so-called authorities; but they belong to us to decide.

Our generation faces the whirlwind of perhaps the greatest crisis this nation has yet seen. The U.S. ruling class is expending all of its energy to frustrate the organic impulses of the American people to achieve a more democratic, peaceful society and a new sense of shared destiny in concert with the rest of humanity. Above all, it is the ideology of the ruling elite that the people have called into question. This must lead to a search for new thoughts, new knowledge, and new ideas by which to determine a new path for America. The stakes, then, are high: will we be pulled backward and make ourselves obsolete, or will we press forward and become worthy of fulfilling this historic task?

It will take an extraordinary effort to find the kernel of truth and human possibility that could unlock a way out of the crisis of our time. Some will choose to burn that bridge.

But for the rest of us—who have not yet made our choice—the bridge still stands, waiting.

Leave a comment