Today, civilization is a concept prominent on the world stage. Recently this October, Russia’s Vladimir Putin spoke on civilization and the civilization-state at the 20th Annual Meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club, an international forum attended by experts and diplomats from 42 countries. Similarly, in March, China’s President Xi Jinping proposed a Global Civilization Initiative to respect the diversity of civilizations, valuing their inheritance and innovations, and advocating for the common values of humanity by strengthening international exchanges and cooperation. Including India and the BRICS+ countries, this tendency encompasses a wide breadth of human civilization and represents the will and aspirations of the vast majority of the world’s population.

Russia, China, and India are asserting themselves as modern civilization-states rising out of ties to ancient civilizations. Their rise presents the reality of a multipolar world order with the possibility of international and inter-civilizational democracy. This possibility cannot be simply reduced into a malevolent threat to the dominating Western neoliberal order, stripped of context. For over the last centuries of modernity, the West has believed that Western civilization is the only one worth respecting and protecting, while all other civilizations are backwards, requiring rescue by assimilation into the West’s universalizing values. Fukuyama’s “end of history” and Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” came out of these assumptions, with dire consequences. The call for the superiority of Western civilization occasionally lifts its benevolent mask to become explicit in the fight against so-called barbarism, as in Israel’s genocidal civilization war in Gaza. Yet it is Israel, backed by the West, that has bombed the Church of Saint Porphyrius, the world’s third oldest church, in addition to schools, universities, hospitals, and thousands of children. Who, indeed, would save civilization, and who appears set on destroying it?

We know in our hearts that civilization belongs to all of humanity. The terms of civilization and modernity are serious and mighty; they carry this weight because they are the birthright of the masses who make up the majority of humankind and have toiled for thousands of years to build civilization—an advanced stage of human development that produces a way of life. Civilization must be protected because it captures an essential current of humanity and its progress. It is thus a category that has a place together with History: the long arc of human history from past to present, with continuity and movement forward. Civilization, though related to History, is a distinct category with new dimensions and meaning. Beyond the materialist stages of history conceptualized by Marx and Engels, civilization considers the qualitative development of human morality, ideas, philosophy, and culture. It points back to our ancestors and the link from them to where we find ourselves today, to the future of our children’s children, and asks: how did we get here?

It is the toil of humanity to build civilization that has ushered in the present stage of history we find ourselves living and acting within. The decay of American empire as the culmination of imperialism, a distinctly modern stage of capitalism, marks a moment which may well be an inflection point in human history. Whether it is called the collapse of the West and the Age of Europe, or the rise of Asia and Darker Humanity, it has been felt by all with either fearful danger, speculative curiosity, or optimism.

In this time, civilization cannot be left as an abstract idea for detached academics or elites to pessimistically problematize or deconstruct, severing the concept from its source. The stakes are indeed high, but the concept of civilization has been thrust in our faces, demanding to be worked out, put into practice, and fought for. The discussion is clearly ongoing: it has not yet been entirely decided as to what extent civilization will be an assertion of the past, with the objective being return to a previous status quo, or an assertion for the future, with the objective being genuine human progress. It is up to the people of the world to weld civilization into the latter.

The American people, too, must take up the question of civilization: what will its meaning be to us, and what will our contribution be to it? Given that America is so young, these concepts may on the surface seem relevant to Americans only insofar as other civilizations might encroach on or threaten our way of life. However, the current crisis of American society—a crisis of legitimacy in the midst of poverty and war—compels us to find a lifeline that can lead us to the future and help us to reestablish our proper place in the world. The call for “civilization,” whether in America or anywhere else, provides a self-conscious category that demands unity and purpose in the continuous struggle for human advance. Thinkers of the Black Freedom Movement saw this possibility the most clearly: they saw civilization in the modern age as a double-edged sword which could be used to either uphold a sterile and doomed system of white supremacy, or decisively pierce through this system to dismantle it for a greater human freedom.

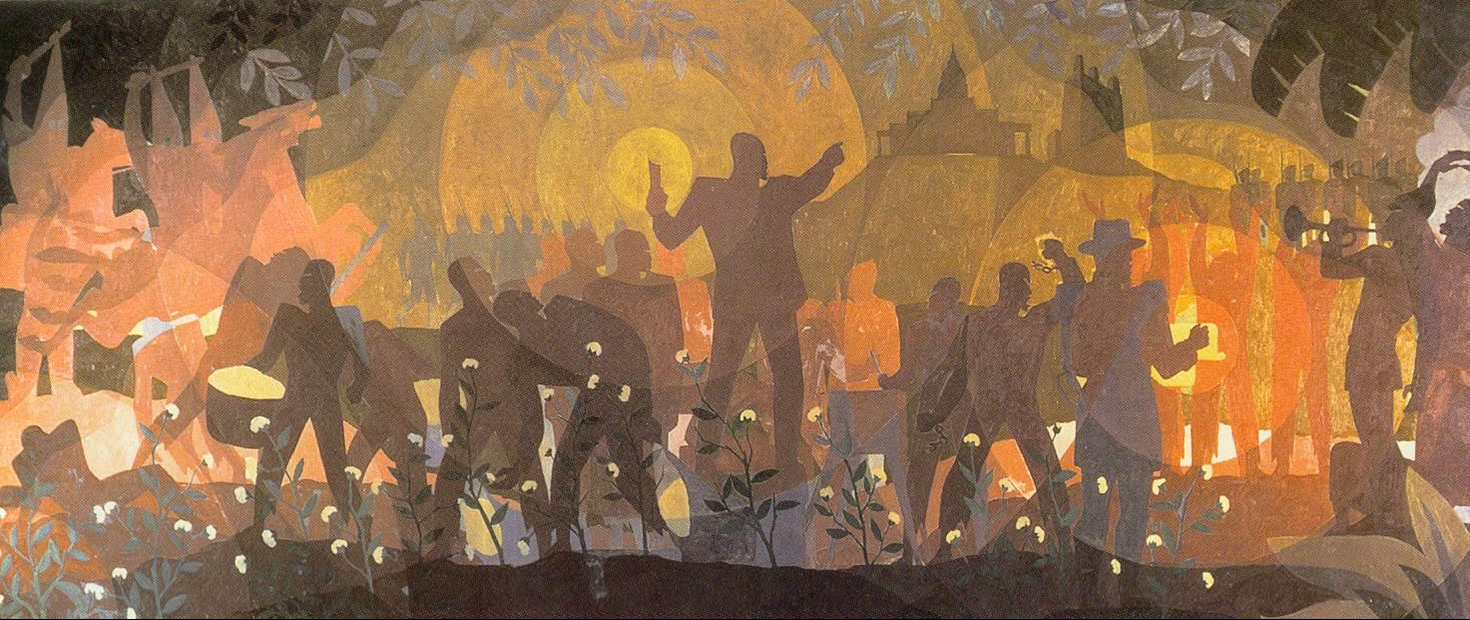

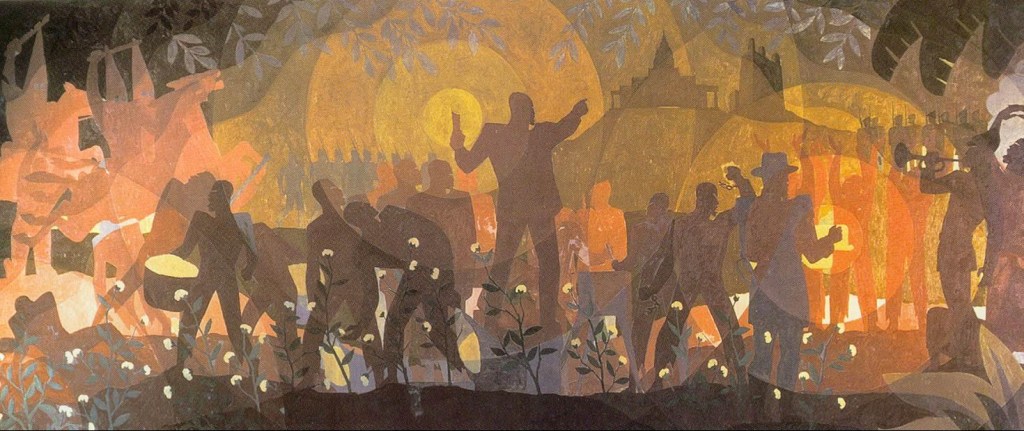

In 20th century America, W.E.B. Du Bois saw civilization as a category for sociological analysis particularly relevant for times of crisis. Amidst the collapse of the West in the period of World War, Du Bois clarified American history, insisting upon the agency of the worker and the emancipation of labor to build civilization. Paul Robeson explored world civilizations through folk music, finding commonality in the working folk of the world. In doing so, he located the true center of civilization and the voice of democracy in the striving of ordinary people, countering the anti-democratic censorship and propaganda of the McCarthy era. Likewise, in a period of world anti-colonial struggle and the expansion of a repressive American war state, Martin Luther King Jr. saw the task of civilization in a world historical context, with the greatest need for moral progress. This struggle in America was helmed by the Civil Rights Movement, which sought the reconstitution of the nation through the abolishment of racism and poverty and the achievement of peace. Shaped by the Black Proletariat, these figures saw their task as achieving a new democracy in America, which would constitute a forward leap for humanity and inject, in King’s words, “new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.”

Although Du Bois lived in a time when the superiority of Western civilization was gratuitously assumed, he attacked the prevailing propaganda that Reconstruction after the Civil War destroyed culture and attempted to overthrow civilization, and the notion that civilization was “the gift of the Chosen Few.” In his monumental book Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, Du Bois asserts that civilization must be understood as a democratic concept which belongs to the masses. For Du Bois, the revolutions that took place in America were fundamental achievements for all of humanity. The American Revolution embarked upon an experiment of suffrage and free property unshackled from Europe’s feudal class structures, while the brief period of Black Reconstruction before a counter-revolution of property demonstrated the innate capacity of the worker to self-govern and rule, producing great works of art, culture, government, and civilizational achievement.

Black Reconstruction is a testament to this human capacity for people’s democracy for the modern renewal of civilization. Du Bois quotes a Black Worker:

“We were eight years in power. We had built schoolhouses, established charitable institutions, built and maintained the penitentiary system, provided for the education of the deaf and dumb, rebuilt the jails and courthouses, rebuilt the bridges and reestablished the ferries. In short, we had reconstructed the State and placed it upon the road to prosperity.”

This great achievement for freedom happened against all odds and assumptions. How could it have happened? What notions stymied man’s vision and expectations? And what kind of thinking could illuminate a deeper understanding of this triumph?

Du Bois’s method of sociology, developed through the category of the Black Worker, sought to account for these larger questions of political movement through the expansive possibility of human agency. For Du Bois, human action operated in a matrix of Law and Chance; agency was a “miraculous freedom of action which is the Uncaused Cause of a certain human deed and of development of human life” and an “inexplicable paradox.” Through his faithful study of human capacity, Du Bois made the connection between the longing and lifeworld of the Black Worker for freedom to the actual building of civilization. Civilization, in their hands, was not defined by the conquest and domination of man, or the accumulation of obscene wealth for leisurely or aristocratic means. Neither was civilization an expression of racial or class supremacy, resulting in the degradation of color and labor for the favor of a small elite. It turned all the assumptions of Western civilization and its exclusivity on their head. Civilization was instead redeemed into a human concept to be wielded for self-consciousness, freedom, and the establishment of democracy through the state.

With the rise of modern capitalism and the development of imperialism, labor was degraded to a new degree. In The World and Africa, Du Bois describes how slavery and colonialism allowed for great industrial and technological progress, as well as cultural exchange, albeit of a forced and unequal nature. In this age, it was the debasement of labor that exploded into war, from the American Civil War to the World Wars. These wars were leveraged by an elite that used white supremacy to suppress democracy and labor as the exploited struggled for freedom.

For Du Bois, the fundamental problem facing civilization was whether or not it would acknowledge who and what it was built upon. He wrote, “Here is the kernel of the problem of Religion and Democracy, of Humanity… The emancipation of man is the emancipation of labor and the emancipation of labor is the freeing of that basic majority of workers who are yellow, brown and black.” So long as labor—especially including degraded slave and colonial labor upon whose backs Western civilization was built—was unfree, religion and democracy reflected an incompleteness and, at its worst, a form of hypocrisy that could not furnish a true way of life for humanity. A civilization founded on lies would be unable to stand on its base, stunting its flourishing. Ultimately, the constriction and impediment of its mass potential would lead to its fall.

Du Bois expanded upon this concept in Russia and America, an unpublished manuscript from 1950, declaring, “No land that lived and breathed like Greece and Lesser Asia needed to die; but any nation that sins against the Holy Ghost must die if truth lives.” This work sought to interpret the similarities between Russia and America in a critical period that saw the United States turn Soviet Russia from a friend and ally against fascism into an avowed enemy of Western civilization with the Cold War. Du Bois highlights the great size and possibility of both countries, and the shared challenge to resolve the conception of a society supported by slaves or serfs. He wrote,

“The United States had opportunity but refused it in the Reconstruction after bloody Civil War. Perhaps Russia is groping for the way out; for a civilization that will not die of its own contradictions. It must and perhaps at least try to place beneath a new conception of culture, a foundation of mass participation in civilization, which Greece never conceived, Rome thought impossible and Europe and America dreamed of but seldom tried to realize.”

Du Bois saw the Soviet Union as an experiment in a new type of civilization, a civilization of, by, and for the worker. Such an experiment was necessary for the renewal and survival of world civilization.

The life work of Paul Robeson was to uplift this mass participation and give it a united voice on the world stage in the fight for freedom. Robeson illuminated this common base of civilization through the world’s folk, who loved him for his task. He said,

“When I sang my American folk melodies in Budapest, Prague, Tiflis, Moscow, Oslo, the Hebrides, or on the Spanish front, the people understood and wept or rejoiced with the spirit of the songs. I found that where forces have been the same, whether people weave, build, pick cotton, or dig in the mines, they understand each other in the common language of work, suffering and protest. Their songs were composed by men trying to make work easier, trying to find a way out.”

Robeson made it a political point to see the highest forms of civilization through African drumming and sculpture, and in folk and sorrow songs, rather than in elite forms of culture such as the classical European symphonic tradition. His framework of the folk, defined as “the songs of people, of farmers, workers, miners, road-diggers, chain-gang laborers, that come from direct contact with their work, whatever it is,” with its music “as much a creation of a mass of people as language,” asserted that these were the people who built civilization. It is the language, music, and culture of the folk that constitutes civilization in its purest and realest sense. Across the great diversity of languages, cultures, religions, and ways of life, Robeson identified a common, universal thread to human civilization shared by the the strivings of ordinary poor and working people, whether they were peasant farmers, miners, laborers, artisans, or factory workers. In Robeson’s conception, there was something familiar in every civilization which provoked a sense of unity, outweighing conflict and difference.

This familiar center that unites human civilization can be understood in many ways. First, it can be understood causally as a touchstone reaching back through the past to the origins of humanity, as all human civilizations trace their roots back to Africa. Robeson noted how remnants of this shared origin persist in every branch of civilization today. Second, it can also be understood as a unique reconstitution of humanity through the shared historical experience of modernity. As Du Bois described in Black Reconstruction and The World and Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and Africa became connected in an enmeshed world system of imperialism through colonialism and the slave trade. This imperialism was crucially distinct from the empires of antiquity in its entanglement of the world and its folk into a single system, newly aware of itself in its vastness and difference. It produced new materials, new industries, and a new ideology of white supremacy in an attempt to order and control the world. It also facilitated the exchange of culture and ideas to produce new human beings: workers, exemplified by the Black Proletariat, who self-consciously conceived of themselves as having a calling for freedom. This created the third, most important force that can unite human civilization today: a new and shared purpose, or a democratic demand, that must be forged for a common future.

Robeson and Du Bois both saw this demand as a cry to find “a way out” of the contradictions of modern civilization, which saw immense material development with moral impoverishment represented by ever-greater exploitation, bloodshed, and war. Could this truly be the meaning of civilization? If a push towards moral and human development was necessary, who would take up the task? Material developments were thus accompanied by great ideological tension. In America shortly after World War II, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke, saying that “the greatest need of civilization today is not the superb genius of science, as important as it is; the greatest need of civilization today is moral progress.” For King, this meant progress in social relations, in human development, and in public life. He insisted upon a revolution of values to resolve the crisis of modern life, saying, “Western civilization is particularly vulnerable at this moment, for our material abundance has brought us neither peace of mind nor serenity of spirit… Our moral and spiritual ‘lag’ must be redeemed.” This redemption of America was the mission of the Civil Rights Movement.

King diagnosed the primary threats to civilization as the triple evils of racism, poverty, and war. Like Du Bois and Robeson, King saw poverty and the degradation of labor as a threat to civilization because without the prosperity of the worker, civilization would be crippled. Similarly, racism systematically suppressed the capacity of human beings and the complete fulfillment of their potential, both Black and white. King described racism and white supremacy as a corrosive evil which could bring down the curtain on Western civilization through internal conflict and decay. In calling for the establishment of a “World House” of human civilization, he said, “If Western civilization does not now respond constructively to the challenge to banish racism, some future historian will have to say that a great civilization died because it lacked the soul and commitment to make justice a reality for all men.”

War was the final and greatest problem that mankind would have to solve in order to survive. It was often caused by racism and poverty, but destroyed human development in an instant and demonstrated the monstrous domination of materiality over morality. With science and technology, there was plenty of food and land, with adequate means of survival and transportation such that we could “enjoy the fullness of this great earth.” Yet, instead of being dedicated to these ends, technology and science had instead pressed to the threshold of atomic war and mutually assured destruction. On these terms, renewal and redemption were impossible. War would thus have to be ended, or else war would end humanity—if not through outright physical destruction, then through the moral devastation and stain of violence.

Peace was thus the democratic demand of moral progress that human civilization cried out for. First, peace was essential to preserve existing civilization and order within society. But beyond the first stage of necessity, the establishment of a true and lasting peace would unleash humanity from its base psychological preoccupations with conflict and allow for the flourishing of greater human potential. An economy based on peace instead of war could rededicate its resources and energy to the development of productive industries, cultural renaissance, and the education and vitality of its people. Development along these ends could renew civilization throughout the world. For humankind as a whole, advancing beyond war would mean the great expansion of human capacity for moral imagination and creativity, and the evolution of social relations towards cooperation and mutuality. All of this was possible to unlock a new frontier in human history, while failure to do so would result in chaos and waste. It was in response to these stakes that King spoke out against the war in Vietnam and asked, “The question now is, do we have the morality and courage required to live together as brothers and not be afraid?”

King was attacked for this stand for peace during the Vietnam War, just as Du Bois and Robeson were attacked for their unflinching stands during the Korean War and the McCarthy period. But they spoke as Americans, striving for the preservation and indeed the renewal of American society, even as they faced the brunt of all its contradictions. James Baldwin described it best in No Name in the Street:

“To be an Afro-American, or an American black, is to be in the situation, intolerably exaggerated, of all those who have ever found themselves part of a civilization which they could in no ways honorably defend—which they were compelled, indeed, endlessly to attack and condemn—and who yet spoke out of the most passionate love, hoping to make the kingdom new, to make it honorable and worthy of life.”

Black America made countless such contributions of love, providing a rich inheritance as a “civilization in potentiality” that can be taken up by the American people today.

An especially great contribution to world humanity was the method of nonviolence—a creative and peaceful method of managing conflict and transforming human relations. It came out of various parts of the world, with the love ethic of Jesus and the satyagraha “soul-force” of Gandhi, but took root in America to bear fruit through the Civil Rights Movement. King recommended that the philosophy and strategy of nonviolence immediately become a subject for study and serious experimentation in every field of human conflict. By embracing this heritage and laying down the sword to “study war no more,” Americans have a unique role to play in working towards the establishment of a World House, consisting of a beloved community of human civilizations which can live together in peace.

The contributions of America to the world are already manifold: from the American Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement which tested and developed people’s capacity to achieve a new nation worthy of its citizens; and from the legacy of art, music, and culture through the Black Proletariat, “who evolved the sorrow songs, the blues, and jazz, and created an entirely new idiom in an overwhelmingly hostile place,” to Du Boisian sociology and the study of that inexplicable paradox of human agency played out especially in the history of Black people in America, which “testifies to nothing less than the perpetual achievement of the impossible.” The Black Proletariat is itself a gift to the American people, to give new possibilities to Western civilization. For America is not a white country. At its best it can become a true synthesis of world civilization, and a futuristic example for the inter-civilizational unity of humankind and human civilization as a whole. Baldwin says,

“America, of all the Western nations, has been best placed to prove the uselessness and the obsolescence of the concept of color. But it has not dared to accept this opportunity, or even to conceive of it as an opportunity. White Americans have thought of it as their shame, and have envied those more civilized and elegant European nations that were untroubled by the presence of black men on their shores. This is because white Americans have supposed ‘Europe’ and ‘civilization’ to be synonyms—which they are not—and have been distrustful of other standards and other sources of vitality, especially those produced in America itself, and have attempted to behave in all matters as though what was east for Europe was also east for them.

What it comes to is that if we, who can scarcely be considered a white nation, persist in thinking of ourselves as one, we condemn ourselves, with the truly white nations, to sterility and decay, whereas if we could accept ourselves as we are, we might bring new life to the Western achievements, and transform them.”

The transformation of America and the renewal of civilization can only be possible through embracing the Black Proletariat, the integral key to the country in determining the brightness or the darkness of the American future to be made.

The concept of civilization declares that this future must carry the old but reflect something new, providing a continuous link to history while simultaneously transcending previous achievements. Today in America, a young country with history still to make, a healthy understanding of civilization and its responsibilities can give depth and voice to the discontented. It can double the voice of the American people calling for an end to poverty, inequality, and war by linking their aspirations to those of the world’s people, who seek democracy of opportunity for advancement. America’s and the world’s people must be freed from the imperialist order to establish equality amongst civilizations.

The task must be to abolish war and fight for peace, for the stakes are exactly those of life and death. These stakes trigger a true and intelligent instinct to call upon the category of civilization amongst those who consider themselves anti-war. But the mask of civilization, as a bulwark against chaos, can also become instrumentalized to provide a false sense of safety by obscuring the brutal facts of reality. This reality is that life has depths of tragedy, consisting of grave crisis and necessity; the only constant pillars for human life are birth, death, and struggle through human agency. We shelter under these pillars and try to construct a roof and sky over our heads through the building of civilization. This is the laborious endeavor to protect humanity and our future, inherited by hundreds of generations before and after us, which we can only renew by accepting our mortality and being responsible to life.

America has a vital concept of civilization to give to the world. This contribution can ensure the continued survival of mankind as well as open up new possibilities for the future. Humanity’s hopes for a new world may depend on how we, the American people, navigate our transition from a dying empire to finally achieving our nation, democracy, and peace. We have a deep current to draw from, and a broad foundation to build upon. These sources are our birthright; we cannot afford to abandon them now.

Readings:

- Race, Class and Civilization: On Clarence J. Munford’s Race and Reparations, Anthony Monteiro

- The Collapse of the West and the Struggle for Civilizational Unity, Archishman Raju

Leave a comment