We wanted to know about your early years and what shaped you. Can you tell us about what North Philadelphia was like growing up?

So I grew up in what was called, and is called, the projects. It was named James Weldon Johnson Homes in North Philly at 25th and Berks. And it was like several square blocks of homes and apartments; and it had trees and grass and flowers and playgrounds. So mostly we stayed within that area. So that was where I grew up, and it was working-class, but outside of the project, people owned their homes. We kind of all lived together and went to school, and it was nice because when I was very young, you didn’t know that you were poor, you just played. That’s what we did, that’s what children do. North Philly was very warm in terms of the adults, and the adults looked after the children. Didn’t matter whose child you were, you had to behave. And if you didn’t, then they told on you, and you got in trouble. It was family-oriented, very supportive of the children. But we had our problems because there were gangs in the area. And I don’t know if you knew anything about the gangs of Philadelphia, but there were gangs, mostly of males. They didn’t have guns back then, but later on they did get guns. They fought each other and were sometimes very terrorizing, particularly of girls. So we had to navigate that as we grew up.

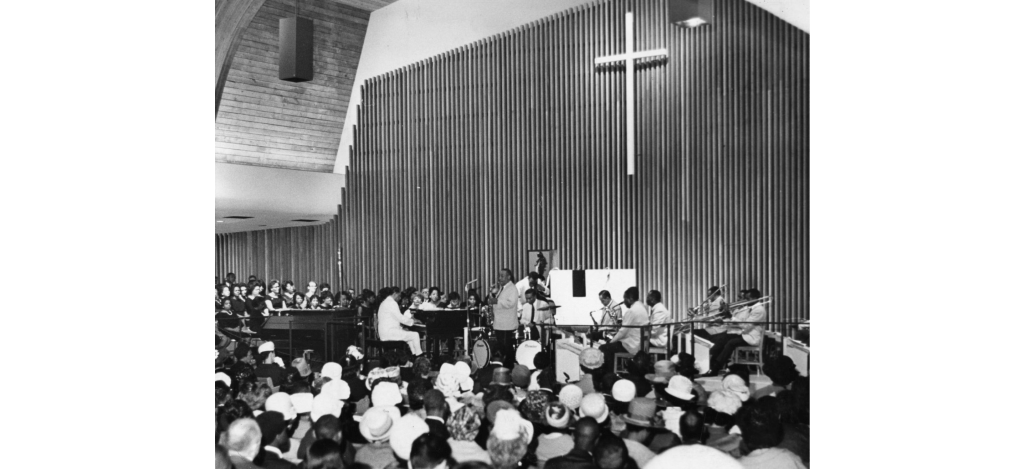

(Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA)

But it was also a place where people went to church, whether the Protestant or the Catholic church. And North Philly was a place where I guess a lot went on. There was a lot of political activity in North Philly, particularly around Girard College and with Cecil B. Moore trying to integrate Girard College. A lot of activity with the Church of the Advocate and Father Paul Washington, who saw the community as his flock and himself as our shepherd. There was Bright Hope Baptist Church, with Reverend William Gray II. And there were other ministers who were instrumental — and what they were doing was to get the status quo to change with respect to discrimination against black people and black workers especially.

Downtown was segregated. We only went downtown basically on holidays, particularly Easter — we’d get dressed up and go downtown. But most of the workers downtown in the department stores, in the restaurants, etc. were all white. A black person may operate the elevator, and at Macy’s (which was then Wanamakers) they may clean, be janitors. But they weren’t salespeople, they didn’t work the register. And it amazes me to think back to how segregated Philly was. We were segregated by race and by class, basically. And as the suburbs developed, the white residents and Jewish residents moved out to the suburbs, which opened up areas for black folk to live in. What was and is known as Strawberry Mansion, a lot of that along the park, 33rd St, was Jewish. They moved out, even significant parts of Broad St were Jewish. Many of the stores — there were stores along Columbia Ave provided jobs for black youth, and black men and women. But mostly, the more affluent black people worked in the post office, some of them worked for the government like my mother’s family. And that was basically it.

As young people, we went to school, we did what we did in terms of socializing. We listened to music. Mostly jazz. Rock ‘n’ roll was just beginning. So what they call rhythm and blues, we listened to, and danced to jazz, for the most part. And Philly was a big jazz scene. We were young, just running around, what did we know. (Laughs) We liked the music. We liked the rhythm and blues. There was a group called the Platters, very sophisticated. And then we had the Dells, all these wonderful people. One of my favorite songs was “Earth Angel”. It was a good time. Although there was poverty, there was also social movement.

So even though I grew up in the projects, I didn’t feel stigmatized at all. Mostly the affluent black folk lived in Germantown, and what they called Nicetown or Tioga, basically. And so they were middle-class, but they were considered more affluent. And they were like professionals. They certainly lived their middle-class lives, with their organizations, sending their children to something called the LINC, and they had Cotillions. It was like a white overlay, with the black community — at least that segment of the black community. The rest of us, we couldn’t care less about Cotillions, and the LINC and all that. It made no sense at all.

(Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA)

Just so we have context of what is happening nationally and globally, what decade are you growing up in?

So I’m growing up in the 50s and in the 60s. We’ll start with the 50s. I’m growing up in the 50s, basically, and I’m in elementary school. By the 60s, I’m in high school and ultimately in college. So during my early years in the Johnson Homes, I was in Gideon Elementary School, which was a new school built in the community at 29th and Sedgley. It had a significant number of black teachers, which was really good. It was very good. It was a good school. There were a lot of great things that we did: we did opera, we took trips, and the teachers were very personable and engaging and supportive. So that was a very good experience for me. We had student government, we had safety patrol, all of that. And considering that we were a mixed, poor, and working-class — and a little bit of middle class — neighborhood, Gideon was appropriate in terms of the educational experience that we received. And I remember being very pleased with it, and actually, my family made friends with many of the teachers. That happened then. There was this kind of affinity toward friendship and a sense of community that included the church and the school. And there was a sense of caring, which in my later years as a teacher we called nurturing. The school nurtured the students. So that we felt secure as young people, secure in our learning.

So the 50s was segregated Philadelphia and the struggle against Philadelphia being segregated by race and economics. Even the black community was stratified as well. But the struggle for equality with regard to black people started way before that; we could go back to Octavius V. Catto and his being killed trying to encourage black people to vote and get the vote. But in the 50s, the ministers — like Reverend Gray and the Shepherd brothers and Reverend Meeks — all came together, and they pushed for equal access to opportunities with regard to jobs. Because if you don’t have those jobs, then your level of poverty is stationary; you don’t transcend it, you don’t become working-class. Therefore you’re not able to buy homes. And I can tell you, a lot of black people did own their homes. They bought homes, they owned those homes, they stayed in those homes. And the neighborhoods were clean and rather safe — except for the gangs. That was a level of crime that took place, I think, as a result of the lack of opportunity.

How long has your family been in Philadelphia?

My grandfather and my grandmother came from the south to Philly. Jeez, maybe in 1920? I’d have to go back into my family history. But maybe 1913, ‘14, ‘15. Somewhere around there. My mother was born in 1921, and she was the second oldest. So my grandfather came from North Carolina and my grandmother came from Virginia — Fairfax County or something like that. So we were in Philly all that time. My grandfather worked as a bricklayer, he also worked on the docks. And my grandmother died when my mother was very young, and so my step-grandmother is who I remember. My mother doesn’t even remember her mother all that much. But my grandmother was involved in bringing people from the south to the north, and they stayed in my grandmother’s house. And she also was involved in getting people to register to vote. So my grandmother was politically active. But we don’t have any pictures of her, and we don’t really know much about her, except for that. And my grandfather was just quiet. They went to church in their community, Little Memorial Baptist Church. And they were lifelong members of that church. And so I remember going over to their house on 22nd and Oxford St and spending time with them. And many family members lived with them until they got on their feet — but not my mom. My mom got married young and didn’t stay married. She and her husband separated when I was two.

So you were raised by your mother?

Yeah, my mother raised four children. My sister was the oldest — she is now deceased. I am the youngest. And I have two brothers in between.

And what did your mother do for work?

My mother worked in the office of a black doctor. And later she went to school and became an LPN, a licensed practical nurse. She did private duty work, so she worked out of an agency which provided patients for her. She would either work in their homes or tend to them while they were in the hospital.

What do you feel were the most important things she taught you and your siblings?

Well, my mother took us to church. She dragged us to church. (Laughs) Got us baptized. She was religious in her fashion, and remained a member of Bright Hope Baptist Church until she passed. And she was a 50-year member of Bright Hope Baptist Church. And she passed at the age of 94. She was very particular about how she wanted things. As a nurse, she wore these starch white uniforms, which she ironed, and these white stockings and the white hat and the white shoes and all that stuff. So she was very particular, and she was organized, focused. She was determined, she worked hard. She had a good work ethic. She was a principled person, and I learned that from her. I have a good work ethic, and I’m determined. I learned determination and persistence from her. I learned positive habits from her.

(Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA)

She was very close to her brothers. They were the Miller clan — they were some strange people. (Laughs) They liked to gamble, to drink, to party — you know, have fun. And they really liked to dress up. So we have all these pictures of them in fur coats, you know, dressed up. But she was family-oriented. She had her own set of problems, which she pushed to the background to make sure that we get educated, and that we go to school, and that we be good people. She was very punctual. When we left elementary school, she made sure that we went to what was called the better school. So for junior high school, I went to Roosevelt, which was a mixed school. It was half black, half white. In Germantown. I hated that, because all my friends went to the neighborhood school, Vaux, and I couldn’t go. I had to take three buses to get to school and get back. So of course I was late all the time. And I was intentionally late — and eventually they kicked me out. (Laughs) Because I was also a little bit mouthy, my transition from elementary school to junior high was also a transition from me being nice, pleasant, and all that, to almost being mean and nasty. Or I could be, depending on whether you got on my nerves or not. But that was just something of me growing up, and beginning to realize some of the differences in my life and the life of those who had more than me. Particularly because my mother made me go to Roosevelt, and did not let me go to Vaux with my friends. So that began my anger within the family and my rebellion. That was my rebellion, right then — maybe not in seventh grade, but certainly by eighth grade. I was hell. I was a hellion. But still, within the community and with my friends, and all adults, I was a pretty good kid.

Something that you’ve been talking about a lot is the church being one of the main institutions for the community, but especially in the 50s when you were growing up, in terms of political action and consciousness. Could you describe more of what that was like for you growing up, when all of these preachers were coming together, and starting these political campaigns?

So back then, I was just a child. I didn’t focus on that stuff — they were in my life, but it wasn’t until the 60s that I became certainly more conscious. So I think that the church, number one, provided for me, in the 50s, a foundation. My mother was religious in the sense that she went to church. I was spiritual in the sense that I was very moved by the life of Jesus, and very hurt by his murder because it did not make sense, in my young mind, that someone who was doing good should be killed for doing good. And so that began my acquaintance with a love for and of humanity, through Jesus. My mother, as a church member, was more involved in some of the political scenery than I was. Because Bright Hope in North Philly — this was around the 60s — was the church to be a member of if you were in North Philly. If you were in West Philly, it was the Shepherd Brothers’ church — I cannot remember the name but this was the one on 42nd St, close to Haverford. And then in Germantown, it was Reverend Meeks’ church. And so all these ministers came together along with Cecil B. Moore around the marches to desegregate Girard College. So I was not necessarily, in the 50s and early 60s, very much a part of that.

However, in the 60s, I became friends with some guys who ran the barbershop. And Tony [Monteiro] may have talked about the barbershop. That is such an experience — the barbershop where the guys got together and talked politics. This was also the time of the Nation of Islam, between the 50s and 60s. I was acquainted with the Nation of Islam, with Malcolm X. A lot of activities and meetings went on within the community. It wasn’t like now, where you can’t get anything in the news. You could get a lot in the news, and there was talk radio — especially talk radio, WDAS, where these ministers and Cecil B. Moore were interviewed. And the [Philadelphia] Tribune played a significant part of educating the community about what was going on. You could get stuff from the regular newspapers as well. But people, certainly black people of course, relied on the Tribune. And then there was the churches. And so it was sort of like the community was blanketed with information about activities and people. Not like now — everything is isolated. But back then, it was just all part of the atmosphere in the community, in the churches — because in the time of [Martin Luther] King, the church was a place where people went to worship, but also to be informed and organize, to be engaged in activities. And it was the church community, actually, that supported the ministers and people like Cecil Moore and the work that they did. And it helped to desegregate Philadelphia, which was very segregated as I told you, in the 50s.

(Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA)

So I went to Temple probably in ‘64. But in my later years in high school, because I went to an all-girls school, I became acquainted with a friend of mine by the name of Earl Green. And he was brilliant — someone that Tony knew. And it was through him that I met the guys from the barbershop. And they talked politics, that was what they did. When I was coming up, we talked politics at the dinner table. We were a family that always talked politics. And my sister was sort of like an internationalist. She was always going out and bringing somebody home from someplace we didn’t know. (Laughs) So we knew about Patrice Lumumba of the Congo. We knew about his assassination. We knew about [Kwame] Nkrumah. That’s the whole side of her life that I didn’t quite know about, but I know she brought it home. So the tendency toward having more of an international view came from my sister. The tendency to be political came from the fact that our family always debated politics and social-economic issues. I would say that there was a lot going on. A lot. And you couldn’t miss it if you were interested. And also we had the great riot in 1964. And so there was a sense of inequality and an anger about inequality as my generation began to come into awareness about social, economic, political issues as well as international issues. So around that time, I met Tony [Monteiro].

By that time, I was living at Temple and Oxford, which was my mother’s house, which is where my mother’s house still is. And Tony was living wherever he lives now, probably at his mother’s house. And Ephraim and Daoud, who were the barbers in the barbershop, kind of acquainted all of us with the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X. Tony knew them and probably went to get his hair cut as well. And so we kind of socialized. Even though it was a barbershop, we also socialized together. Because Ephraim and Daoud played music. They played guitar. Ephraim would get jobs in bars to play jazz. There was a lot of that back then, little trios or etc., and they paid for that. That was one of the things that we did. We listened to music, danced, etc. So Tony and another good friend of mine — I don’t know if Tony has talked about Brenda Ithana, but it was the three of us who actually did the anti-apartheid work in Philly. Particularly Tony, it began for me with Tony.

One of the assumptions about today in terms of politics and information is that because we have the rise of the internet and social media, people have more access to information. But actually from what you’re saying, there was already that information so widespread in the community when you were growing up in the 50s and 60s. And actually it’s harder to get the right information today than it was back then.

That’s right. Corporate media was not necessarily directing the message then as it is today. And controlling the message, and even creating the message. Mass media was not so much a tool of corporations or of the state. They were still independent, and they did cover all kinds of issues. Like when [Fidel] Castro came to Harlem — that was all covered. We also had black media, which was Ebony and Jet — that all went under. I learned about Emmett Till through the black media, and there was a picture — there was a grotesque picture of his face that was published, and his mother allowed it to be published because she wanted everyone to know what had happened to her son. So yes, the information — we could do a press release and it was picked up by the media. We made announcements through the media. But the internet is awash with too much. It’s just too much there. You can get information through the internet but it’s not as necessarily widespread as it needs to be nor is it all that accessible. Back then, the information was accessible — through TV, through radio, and through print media. And it was not as controlled as it is now. I think the internet is a great tool, but I think you have to wade through too many commercials and you have to be careful of the sites you’re going on. But you can access a lot of data that is now made available online if you know what you’re doing.

Leave a comment