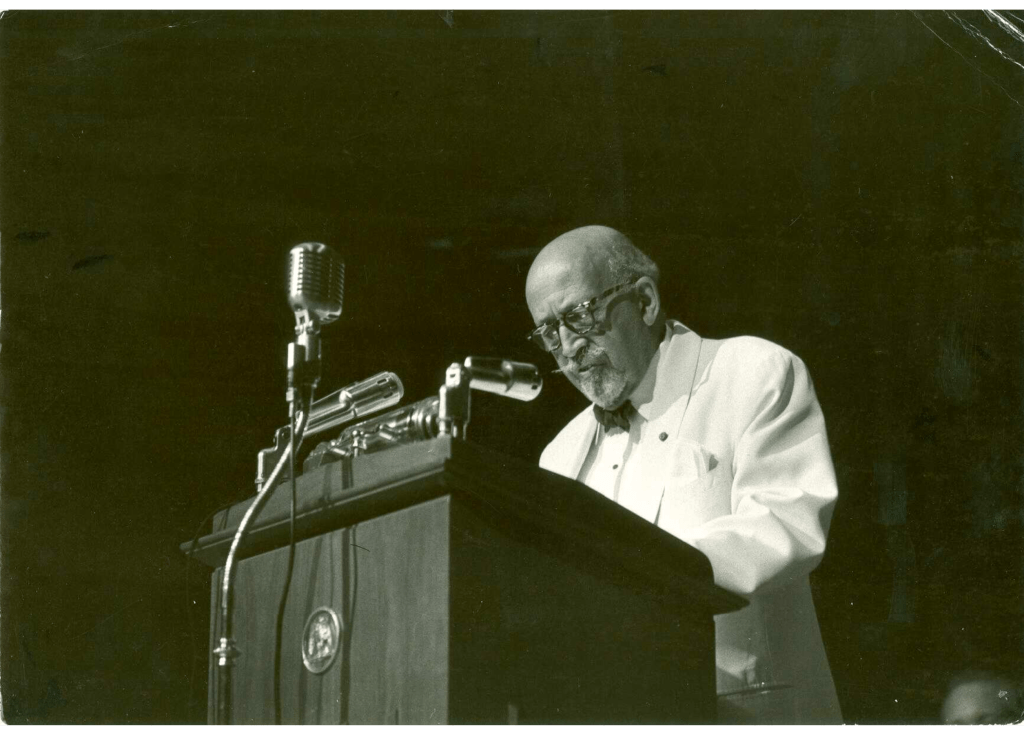

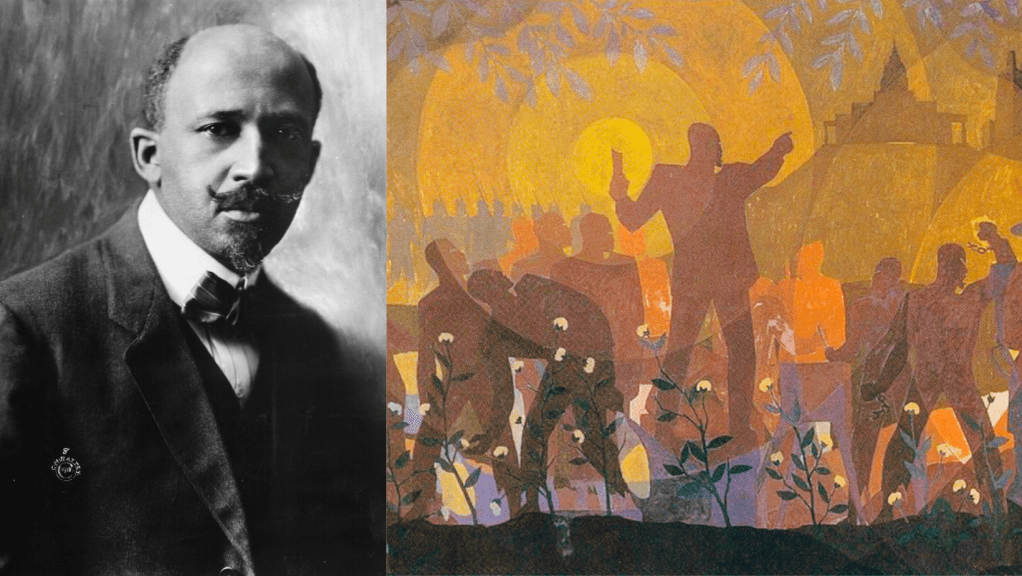

We are publishing Dr. Anthony Monteiro’s keynote address from a discussion of “W.E.B. Du Bois and the American Revolutionary Process” on September 30, 2022, as part the Saturday Free School’s 10th anniversary conference. This essay was first published in Vishwabandhu Journal in an earlier version.

This presentation is my effort to theorize a revolutionary synthesis of V.I. Lenin’s and W.E.B. Du Bois’s thinking on paths to revolutionary democracy and socialism. This synthesis is a theoretical guide for understanding a Fourth American Revolution. A revolution which builds upon the Third American Revolution, what is generally called the Civil Rights Movement. My central assumption is that a new qualitative level of theory is called for in this moment of crisis and what could become a new stage in the struggle for revolutionary democracy and socialism. I furthermore use the concept synthesis in its dialectical meaning, i.e., a new quality emerging from a unity of two ideological movements. The Leninist and Du Boisian movements, while not antagonistic, remain in dialectical relationship, moving towards a new synthesis. I will try to outline both in this essay. However, I view Du Boisian ideas, social scientific methodologies and conceptualizations of world history, the place of Asia and Africa in contemporary history and the function of race and racism in shaping class and class struggle, to be of such importance as to make him the more dynamic part of this dialectic. Put perhaps another way, given the U.S. and world crises, Du Bois is the creative and dynamic side of the Lenin-Du Bois dialectic.

THE NATION’S MOST PROFOUND POLITICAL CRISIS

The United States of America is in what might be the most profound crisis of its history. The nation is divided in ways never seen. Polling data show 80% of Americans believe the country is moving in the wrong direction; 60% say the government is corrupt and does not represent them and 25% say they would support using arms to change the government. Most Americans disapprove of President Joe Biden’s performance in office and less than 25% support his administration’s economic policies. The approval of the U.S. Congress is below 20%. Few Americans trust politicians, government, the media, the courts, universities, or elites. The nation is becoming ungovernable. Gun violence has taken over major cities. The U.S. population feels unsafe.

Many socialists have abandoned revolutionary theory and become reformists linked to the Democratic Party. Some have retreated into sectarian debates about Marxism, the Russian revolution, and other matters. Others—claiming to advance the struggle against racism and for Black equality—nihilistically trash the American Revolution, arguing that fascism was coded into America’s political DNA from the very outset. They claim that the American Revolution was a counter-revolution to uphold slavery, that the Civil War was but another episode of a racist and ultimately fascist nation. Putting aside the logic of the many arguments about the past, these claims are about the present and the future. What they are saying is that there is no future for the American people. It justifies joining the ruling elites and the Democratic Party. They preach pessimism and nihilism. It continues a trend begun in the 1980’s where academics and public intellectuals abandoned working people. Most of the Left cannot figure out a way out of the crisis. Many have written working people off, claiming they don’t have the moral or political capacity to transform the crisis into a struggle for democracy and working people’s rights. However, this moment cries out for revolutionary theory which fits this moment. Such theory must accurately account for specificities of U.S. history and the political and moral capacity of its people. It must address the logic of the formation of the U.S. ruling class, the working class, the historical emergence of the Black proletariat, and the formation and history of the U.S. state.

Hence, their anti-capitalist protests are but a veil to hide their actual essence as apologists for the rule of neoliberal authoritarian elites. The theorists of these claims in turn say that the political, intellectual, and financial elites are the most progressive and anti-racist part of the white population. They disparage every call for the unity of working people. A U.S. civil war is possible. Some say we’re in a pre-revolutionary situation. Both are possible simultaneously.

A DARK AND TRAGIC LANDSCAPE

Most Americans are either unemployed, under-employed, poor, homeless or ill-housed, hungry or ill-fed, uneducated or poorly educated, drug addicted, mentally or physically ill, and imprisoned. Life expectancy is in dramatic decline and suicides have reached historic levels. Stranded populations of young, mainly white people, exist on precarious islands of drug addiction and homelessness, encamped in deindustrialized urban neighborhoods. Children and teenagers are experimenting with and becoming addicted to lethal drugs. Many overdose on them. Suicide has become a life choice for thousands of children and teenager as an answer to overwhelming social and personal crises. Fear grips the people, forcing many to retreat from society and the struggle for change. Children and youth are in the deepest distress. They have been abandoned by our society, which is driven insane by greed, the worship of obscene wealth, extreme materialism, and war. For tens of millions of children and youth, life is a long cold winter. This social, economic, and political situation is unsustainable. For most Americans this is a dark and tragic landscape. The nation prepares itself for a great catastrophe, or perhaps for a radical change.

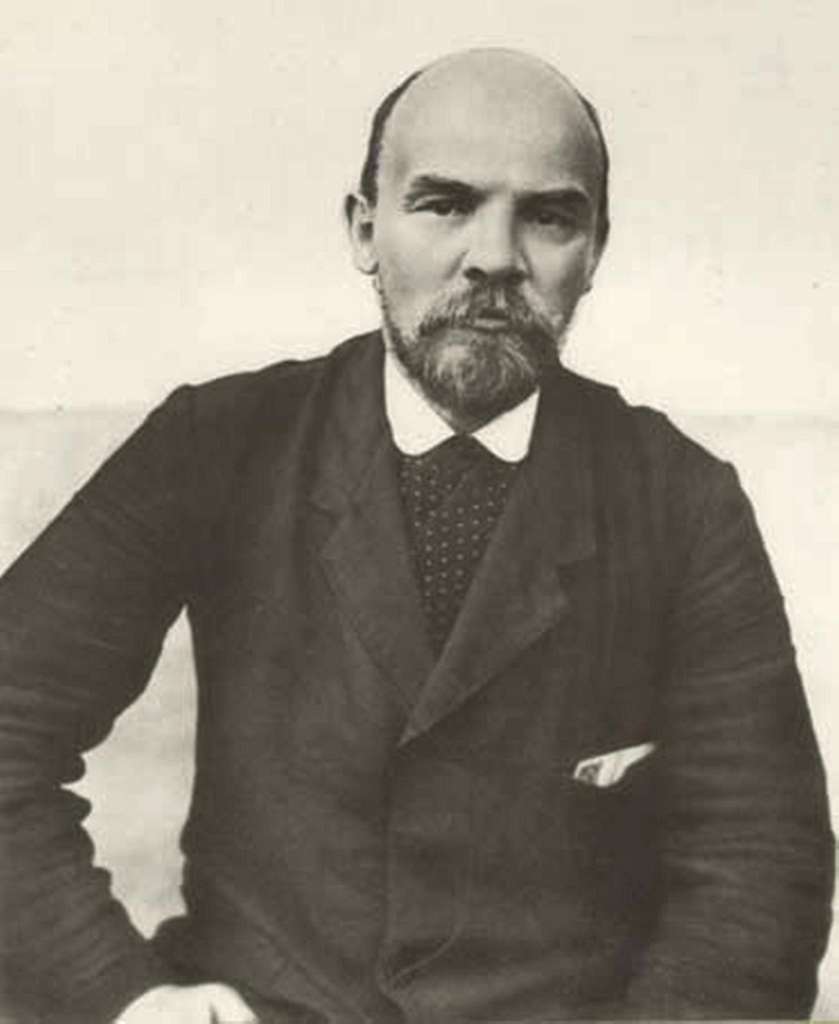

A GREAT REVOLUTIONARY RUPTURE AND LENINISM

The greatest revolutionary rupture of modernity was the Russian Revolution. The great theorist of that revolution was V.I. Lenin. The theory of the Russian Revolution is Leninism. Lenin proposed against most revolutionaries of his time that imperialism could break at its weakest link, rather than its core, and that Russia could be the vanguard of the world socialist revolution and the first seizure of state power by the proletariat in alliance with the peasantry. Lenin bent philosophy, history, theories of the revolutionary party, the state and the class and national liberation struggles, and science to one aim: the revolutionary struggle for power.

However, the logic of the Russian Revolution must always be scientifically understood, by which I mean, its general laws and historical specificities. What we learn from the Russian Revolution must be creatively and scientifically applied to the revolutionary process of the United States.

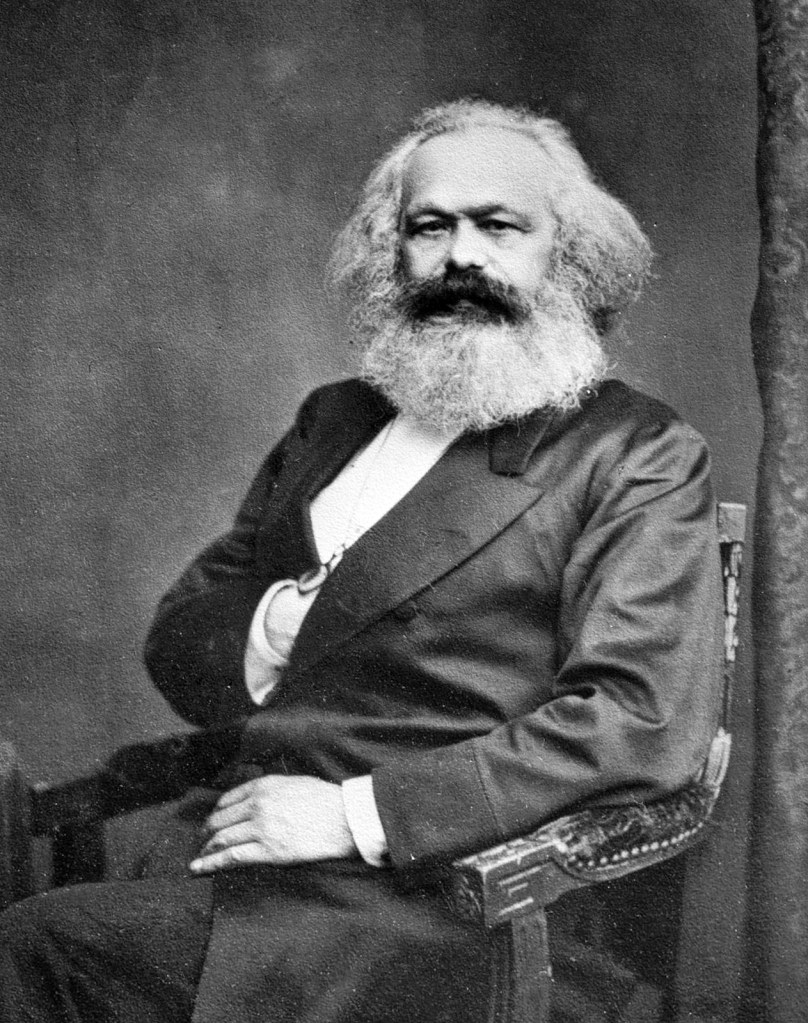

For revolutionary theory that befits our conditions and our time/space particularities and to advance it, it is necessary to scientifically study the U.S., its history and the capacities of its people. In this respect the Du Boisian body of work is crucial. He produced works that are a foundation for revolutionary thinking and practice in the 21st century. They are among the most important works in U.S. and modern intellectual history. Among them are, Black Reconstruction in America, Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward An Autobiography of a Race Concept, Color and Democracy, The World and Africa, In Battle for Peace and Russia and America. They can be viewed as a single whole, with an integrity and commonality, and a single-minded commitment to revolutionary change. They evidence a revolutionary historiography, as well as epistemological and philosophical ruptures and relocations, and a radical and creative sociology. He called Karl Marx the most important modern philosopher. He made no bones that much of his research considered Marx’s and Lenin’s scientific discoveries. His sociological and historical research introduces experimental methodological apparatuses. The way Du Bois did sociology enabled social science to get at very difficult to discover truths. He deploys logics in unusual ways, seeking laws of social development and what he calls “uncaused causes.” He bends and revises Marxian assumptions geared exclusively to Europe; and explains how race, class, and civilizational questions must be addressed if we are to understand the forward trajectory of history to socialism and communism. Du Bois’s oeuvre is, arguably, the most significant body of revolutionary thought produced in America. His thinking and research occurred in a time when the U.S. had become the major capitalist nation, with an imperial and military reach that surpassed any previous imperialist nations. Let’s recall Lenin theorized from what Marx had discovered but applied it to a new capitalist epoch—the epoch of imperialism and finance capital—and to what was considered a “backward” nation. Du Bois was doing something similar, though not the same; he was applying Marxian conclusions and his understanding of the Russian, Chinese, and the African and Asian revolutions to the imperialist epoch of capitalism. However, he did so under conditions when the U.S. was becoming or had already become the dominant capitalist nation.

Du Bois, on the other hand, had to consider the conditions and grounds for democratic and revolutionary struggle in the U.S. While the arc of his work bends to this one aim, his Black Reconstruction in America is perhaps the work which best crystalizes his thinking on revolutionary change. Du Bois considered this work more than historical description or mere explanation of past events, but as a scientific work that probed the patterns and laws of America’s social development and its potential for revolutionary change. It is a study of race and class, but in the end, it is a study of the class struggle in the U.S. As a scientific innovation Black Reconstruction stands alongside Marx’s Das Kapital and Lenin’s Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.

DU BOISIAN SOCIOLOGY AND REVOLUTIONARY THEORY

Du Bois developed science and theory that would address the burning questions of U.S. history and especially of the Black worker, the enslaved proletariat, and how and where they stood in relationship to the proletariat in general and the movement of American history. Du Bois like Lenin saw history as critical for any social understanding. History informs and contextualizes political and ideological events. However, Du Bois is a founder of modern sociology. Rather than privileging political economy, as Marx and Lenin did, Du Bois sees sociology as the critical social science for understanding human complexity, capacity, and human action. Du Bois’ sociology is multi-methodological. Epistemologically he was a scientific materialist, believing there is an objective world and there is truth. Sociology, he said, is the study of man, but a study of humanity in all its complexities. Hence, while Du Bois asserts the importance of laws of society, he insists that alongside laws there is chance. Chance reflects the uniquely human, the unpredictable and possible in human behavior, a type of sociological uncertainty principle. In this respect, sociology provides a richer framework for understanding human beings than does political economy and its laws of economic behavior. As articulated by Du Bois, sociology better explains race and racial oppression and its effects. It better explains the relationships between segments, groups, and individuals in the working class, the function of race and racism within developed capitalist societies and the relationships between workers and other classes. Legal and political racial separation creates specific conditions of class and class struggle in the United States. Throughout his sociology Du Bois is always considering the capacities of people to act purposefully in order to change exploitative and racial oppressive social relations. His sociological methods are always asking the question, “What is possible? What are human beings capable of?” In this regard his sociology has a dynamism to it, rather than static numbers counting.

Most striking is his notion of double consciousness, which is part of the phenomenological and existential realities of Black people and Black workers in the U.S. He asserts that Black people see the world in twos, through the lens of blackness and alternatively through the lens of the white world. This twoness impacts class consciousness among Black and white workers, in specific and concrete ways unique to the United States. Double consciousness is not separated from class consciousness. The two are in complex ways interactive; in many respects, in ways we have yet to completely understand. Furthermore, the struggle for the working class to become conscious of itself as a class and to become a class for itself must engage with double consciousness and the struggle of Black people to become a people for themselves. This is a level of complexity not considered within Marxism but is unavoidable in understanding the logics of class struggle and revolutionary transformation.

It seems perfectly clear, therefore, that a theory of the revolutionary and democratic struggles in the U.S. cannot avoid Du Bois’s sociological and historical innovations. His scientific discoveries are tied to his methods of doing social science which are connected to his sociology. His methods of empirical research, from which he gathers data and sociological facts, such as the actuality of racial separation, double consciousness, and the central role of the Black worker to the class struggle, are necessary to understanding class and race and the class struggle in the U.S. Du Bois’s sociological methods give us ways of seeing and explaining concrete conditions of working people and especially of Black folk. When applied to actual struggle, Du Bois’s sociological methods give a clearer understanding of working people than does political economy. Political economy explains large structures of economic and material production, and the reproduction of economic and class relationships. It fails to explain actual human beings, their limits and potentialities, and the possibilities of human action. In other words, sociology better explains the complexities of the human factor in the processes of social change. Du Bois bends social science, as sociology, to the human in all its complexities and manifestations. His research and theorization present more accurate understandings of the potential of social and revolutionary change, and are therefore unavoidable in any theory of revolutionary science.

DU BOIS ON CIVILIZATION AND PATHS TO COMMUNISM

Du Bois’s writing on democracy, socialism, and communism clarifies many of the aims of his sociology and historiography. In 1961 before leaving for Ghana to restart work on his Encyclopedia of Africa and to live his final days, he joined the Communist Party of the United States, declaring, “I believe in communism.” The father of Pan Africanism, the towering theorist of race, a vanguard in the anti-colonial struggle, was, as importantly, one of the great theorists of communism. For the final forty years of his life, he theorized and rethought possible paths to socialism and communism. After a month in the Soviet Union in 1926 he wrote, “If what I’ve seen is Bolshevism, I am a Bolshevik.” In an extraordinary conclusion Du Bois insisted that Asia’s and Africa’s advances to socialism and communism would grow the global economy and widen opportunities for workers throughout the world. He inverts the Eurocentric view that Europe would lift Africa and Asia.

In an unpublished manuscript Russia and America, Du Bois applies his historical and sociological methods to understanding the concrete possibilities of communism as a social system. It is a defense of socialism in the Soviet Union, a theorization of the possibilities of socialism becoming a world system, replacing world capitalism, and socialist globalization coming through Asia and how the probable path to communism would witness an Asian leap through the centuries. However, the transitions from socio-economic backwardness to socialism and finally communism would require social scientific knowledge and sophisticated planning. All of this would bring forth a new epoch, a new world socio-economic system, and new human civilizations.

The prerequisites for communism were, he theorized, more readily grounded in the values of Asian and African civilizations, especially ones that had had socialist revolutions and established the democratic dictatorship of the proletariat. Du Bois thought creatively about questions such as forms of state power, including the dictatorship of the proletariat and what I prefer to call the state of the entire people and what is today called the civilization state. He thought in new, unprecedented ways, about a new type of communism (what he called “a different kind of communism”) based on a new way of thinking, and forms of state power and people’s democracy rooted in Asian civilizational values. He creatively synthesized several modalities of social scientific, philosophical, and historical investigation; comparing civilizations and their capacity to achieve communism. These interrogations have meaning in the 21st century; a century where Asia is overtaking the West and the U.S. is confronted with domestic political instability and a rising crisis of government and bourgeois class rule.

He saw the Russian Revolution in civilizational terms and as essentially more Asian in potentiality. He viewed it as the beginning of reclaiming the civilizations of the East as part of a march to communism, while the West on its own could only manage New Deal type social democracy. Hence, for the progressives and radicals in western nations, their ultimate contribution to the forward march of human civilization was to fight for peace and against imperialist wars. The fight for peace is a form of mutuality and internationalism. Africa and Asia’s advances to socialism and communism, would create global circumstances for the working classes in the West to be pulled along by winds of revolutionary change coming from the East. The advances of the East create favorable conditions for revolutionary change in Western capitalist nations.

DU BOIS AND LENIN ON CLASS STRUGGLE AND CIVILIZATION

One of the towering accomplishments of Russia and America is Du Bois’s theorizing of the relationships between civilization, class struggle, socialism, and communism. The Russian Revolution became for Du Bois a concrete area of research in history and sociology. He studied the dictatorship of the proletariat as a form of people’s democracy and people’s defense of their revolutionary triumphs. Lenin, he said, is “one of the great men of this century” and a social scientist: “Lenin was not the sort of modern Sociologist, who boasted of his science, and did nothing to discover its laws.” Du Bois concludes, “following Karl Marx, he saw the rhythm of history and determined to plan human life in accord with known knowledge.” And therefore, “He studied not only the written word of history and economics, but the actual current deeds of living men.”

Du Bois saw China, like the Soviet Union, as a civilization where the same questions could be studied. Ruined by civil war, feudal relationships of production, and foreign control, China, for him, remained indispensable to understanding the possibilities of communism: “Any attempt to explain the world, without giving China a place of extraordinary prominence is futile.” Speaking of a new socialist economic system in China after the Chinese Revolution, Du Bois says, “It would take a new way of thinking on Asiatic lines to work this out, but there would be a chance that out of India, out of Buddhism and Shintoism, out of age old virtues of Japan and China itself, to provide for this different kind of communism, a thing which so far all attempts at a socialistic state in Europe have failed to produce; that is a communism with its Asiatic stress on character, on goodness, on spirit, through family loyalty and affection might ward off Thermidor (counter-revolution — A.M.); might stop the tendency of the Western socialistic state to freeze into bureaucracy.” He concludes, “It might through the philosophy of Gandhi and Tagore, of Japan and China really create a vast democracy into which the ruling dictatorship of the proletariat would fuse deliquesce: and thus, instead of socialism ever becoming a stark negation of freedom of thought and a tyranny of action and propaganda of science and art, it would expand to a great democracy of the spirit.” Critical to all of this is breaking the over-determination of capitalist laws of development over human social relations; they would be replaced with the laws of socialist development leading to communism and freedom. This, in Du Bois’s thinking, is the movement from Necessity to Freedom, from over-determination by the laws of capitalist development to full human actualization and the new human being. The great tragedy, however, for an emerging Pan Asian civilizational convergence, was that Japan “learned Western ways too soon and too well and turned from Asia to Europe.”

DU BOIS AND LENIN ON THE CAPACITIES OF THE WORKING CLASS

Du Bois’s and Lenin’s thinking intersects at a critical political/theoretical moment (which relates to current debates), i.e., could “backward” peoples leap to the vanguard of revolutionary struggle. Du Bois explored these questions in Black Reconstruction and Lenin in the essay “Our Revolution.” For Lenin, could the “backward” Russian proletariat be the vanguard of world socialist revolution? For Du Bois, could the Black proletariat lead the American working class and the democratic struggle and even build a democratic dictatorship of the Black proletariat in the U.S. south after the U.S. Civil War? Lenin answered that the small, relatively undeveloped, and “backward” Russian proletariat could lead a socialist revolution. For his opponents, in for example, the powerful German Social Democratic Party and their followers throughout Europe, including Russia, the consensus was that Russia was too backward and too weak to either carry out a socialist revolution or hold on to it if they did. Lenin made a civilizational repositioning of the Russian Revolution away from the European left and towards Asia.

Working class socialists like Eugene V. Debs and others, Du Bois reasoned, understood class, class struggle, and socialism in dogmatic and narrow ways. For him they did not understand the full scope and complexity of the class struggle, nor its relationship to racial oppression and the Black worker. Du Bois invents a wider worldview than normally associated with U.S. socialists; one that when looked at today shows a more accurate path to socialism.

Could it be, given the claims about the backward U.S. working class, that we are confronted with questions that Du Bois and Lenin engaged? The academic and journalistic consensus argues that the U.S. working class, especially white workers, are irredeemably backward. Du Bois insisted that the Black worker had the capacity to be the main force fighting against slavery. He says 500,000 of them, during the Civil War, participated in what was effectively a general strike by putting down their tools, refusing to work and leaving the plantations. He also showed that 165,00 of them joined the Union army and fought against the South. His conclusion was that Black workers were in the vanguard of the fight for their freedom. During Reconstruction, he argued that a democratic dictatorship of the Black proletariat was possible in several states of the South.

Lenin under different circumstances makes a similar argument concerning the question, how could Russian workers bring about a socialist revolution and how, without the European working class, could they hold on to it? He says, “[B]ut what about a people that found itself in a revolutionary situation such as that created during the first imperialist war? Might it not, influenced by the hopelessness of its situation, fling itself into a struggle that would offer it at least some chance of securing conditions for the further development of civilization that were somewhat unusual.” And then asks, “why cannot we begin by first achieving the prerequisites for that definite level of culture in a revolutionary way.” Lenin’s and Du Bois’s argument is that a “backward” working class could, through struggle and given a historic crisis such as world war, civil war or economic catastrophe, make a qualitative leap and in so doing not only throw off the chains of oppression but create conditions for a new civilization and new human beings. This, despite the existential terror of daily life. Du Bois makes a similar argument concerning Black workers. They were, he insisted, “everything African” and “a civilization in potentiality”; he theorized a new civilization might emerge from their struggle for freedom. Though forced into “backwardness” by oppression, they could free themselves and create a new civilization in the U.S. That remains possible.

Du Bois and Lenin argue against the gradual freeing of the “backward” people by more “advanced” and enlightened classes. The intensity and catastrophic character of a crisis can propel the “backward” to the vanguard of humanity. Both Du Bois and Lenin argue that in making revolution, the “backward” start the process of making civilization—showing that backwardness is not absolute.

As to the claim that the U.S. working class is “backward”; Du Bois and Lenin would respond, the “backward” often leap forward through centuries to become the vanguard. Moreover, the class struggle can be viewed as a fight for civilization, for a new civilization; in specific moments of systemic crisis, the class struggle is more than the class struggle. Upon the shoulders of “backward” people rides the future of humanity. This is what Du Bois concluded about the slaves and Black folk after slavery; it is what Lenin concluded about the future of the Russian revolution. If a working-class left is to emerge it must attack the idea that the U.S. working class is irredeemably backward. Otherwise, the Left cannot be a force for revolution in the U.S.

BLACK RECONSTRUCTION, THE FOURTH AMERICAN REVOLUTION AND THE LAST WHITE NATION

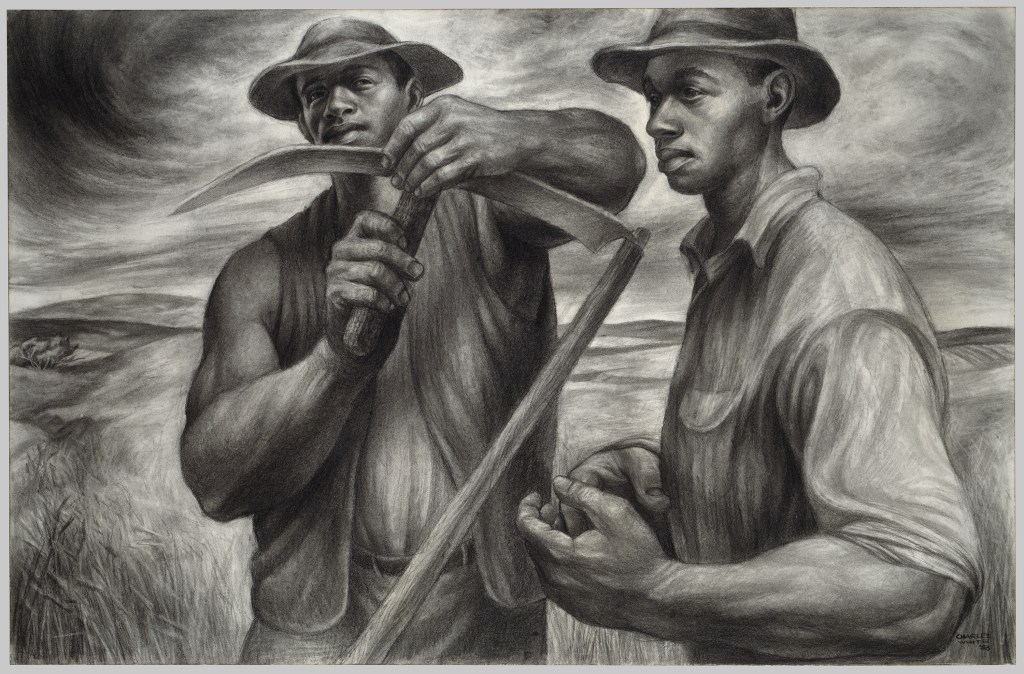

Again, Black Reconstruction in America is an extraordinary and complex work. From a social scientific and historiographic perspective, it is radically new. Its subject is revolution and the revolutionary process in the U.S. Central to this is the class struggle in the U.S. The strategic subject is the Black proletariat—the formerly enslaved African proletariat.

The Black proletariat is in logical terms an explanatory category. As such it explains more than itself, it explains the principal trajectory of U.S. history and the class struggle in the U.S. At another level it explains the race-class dialectic in U.S. history. In explanatory and concrete historical terms, the Black proletariat is more than itself.

The study of this unique subject in history immediately establishes that the work is something new in history and social science. However, for the first time the Black proletariat is treated as an agent of history. The study examines their moral capacity in order to assert the Black proletariat as liberators and vanguard of the U.S. revolutionary process. Beginning where the text begins, a first question is why here; why the first chapter is “The Black Worker.” The answer is because Du Bois wishes to say something about class conflict in the U.S.; its historical grounding is the slave system, the color line, and whiteness. All of which he addresses in the text. But a larger philosophical and historical-logical point is being made. To achieve his objectives Du Bois must consider many areas of philosophy, logic, and epistemology. Du Bois writes as an anti-capitalist. Looking back to his doctoral dissertation, “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade” (1895), one could argue that he sees the class conflict in embryonic form starting in the holds of the slave ships as well as on the plantation. Again, this is an extraordinary insight that is embedded in and an organizing assumption of Black Reconstruction in America. Furthermore, Du Bois must find a way to account for both the capitalist system and the white supremacist social system. He must attempt to see how they constitute a single system.

A WORK OF APPLIED HISTORICAL LOGIC

The work can be considered a work of applied dialectical logic, more specifically historical logic as applied to U.S. history. Du Bois is obviously familiar with Hegel’s and Marx’s dialectics, that history moves through contradiction. For Marx, the chief historical dialectic is that between classes. Du Bois, however, applies historical logic to the realities of U.S. society, where the primary accumulation of capital was on the backs of what was an enslaved African proletariat. This situation created a specific socio-historical situation, what I call dialectics by three, or dialectics by triads—the Black proletariat, the white worker, and the dominant or ruling class. This move is logically necessary given the principal subject of the work, the Black proletariat, which is both part of the working class as a whole and part of Black people as a whole; the world outside of human consciousness becomes part of it through conscious and purposeful activity, both the purposeful activity of the scientist and the purposeful activity of the subject of research, in this case the Black worker. It is a work of history and sociology and philosophy. But more than this it is a work of logic, philosophy of history, theory of the class struggle, theory of democracy and state formation. As such it defies being pigeonholed as one thing, despite the wishes of professional historians.

To understand this work one must be prepared to engage in its complexity and to see the multiple areas of philosophy and theory it engages. As a work it is the equal of Hegel’s Science of Logic and Marx’s Capital. In the history of knowledge, it is a scientific breakthrough and is an epistemic and revolutionary rupture in multiple fields of knowledge and science. Its subject is revolution and the revolutionary possibilities of U.S. history. Hence, to read this book means to respect its complexity. It is far more than recounting history and the presentation of historical facts. It is more than description or even historical explanation, narrowly thought of. It is more about the future, the arc of U.S. history, its logic and rhythm. All of this must be said because most readings and commentaries of Du Bois’s oeuvre by historians (philosophers, logicians, and theorists of class struggle and revolution have completely ignored it) diminish it in dismissive ways and are satisfied with consigning it to a museum. In this respect as theory, it is living and relevant for this moment in U.S. history.

THE BLACK PROLETARIAT IS THE PROLETARIAT IN ITS BECOMING

The first chapter is titled “The Black Worker.” A fact seldom mentioned. Moreover, to understand the arc of the work, the reader must begin where Du Bois begins. Upon this an entire set of other investigations and conclusions are asserted, such as the general strike, the dictatorship of the Black proletariat, new forms of democracy, a wage for whiteness, etc., and other testable hypotheses. However, more than a mere chapter title, the Black worker is a decisive analytical category. The Black worker, put another way, is at first an enslaved proletariat. It is the enslaved proletariat (as Du Bois commented, “everything African”), but it is more; as a scientific category (a lens through which to scientifically observe the world) it is more than the Black worker. It is both historically specific to a certain time and space, but it goes beyond what is specific. As a scientific category it is both concrete and universal, it is both itself and the thing itself, it is both the Black worker and the working class. The Black proletariat is, in its becoming, the U.S. working class itself. Its essence is its becoming. It signifies then and now the revolutionary capacity of the working class itself. A great irony of the dialectics of the class struggle and revolutionary potentiality is that the enslaved proletariat is the proletariat in its becoming, i.e., in its being what it must be.

In this respect Du Bois’s concept of the proletariat struggle is both Marxist and Du Boisian, it transcends Marxism as such. We have, therefore, something new, yet deeply revolutionary. It explains the specifics of class formation and class struggle in the U.S.

DIALECTICS THROUGH THREE—TRIALECTICS

The Black worker is both a category of understanding and a concrete historically constituted reality. In this respect there is a dialectical logical connection between the abstract category and the concrete reality. But logically the concrete phenomenon exists in its becoming. But what is its logical arc? It is, in its becoming, the U.S. working class itself. The working class will become what the Black worker is; thus realizing James Baldwin’s (“Notes on the House of Bondage”) claim that the U.S. would be the last white nation.

I wish to conclude by returning to logic. I have proposed that Du Bois discovers a new historical logic. I have called it dialectics through threes or better, I think, trialectics. This logic accounts for the capitalist system and the white supremacist social system in dialectical interrelatedness. The Black worker, the white worker, and the dominant, i.e., Capitalist class are the three classes in the social system overall.

Logic in the two dominant construals, Aristotelian and Hegelian—logics of identity and logics of negation—reflect the levels of society’s development and of scientific and philosophical developments. For Hegel, science is attached to Newtonian physics. The world gravitates to stability, from theses to negation and synthesis. Science has advanced, requiring new ways of knowing a world that is more complex than Newtonian, even Darwinian science, conceived. Since the discovery of the theory of relativity, quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle, quantum computing, new geometries and phenomenologies of subatomic particles and new sciences of complexity, new systems analysis, and far from equilibrium dynamics, new logics of the objective world have had to be considered. Similarly in social science, theorizing new ways of understanding everything from macro- to mid- and micro-level social structures are occurring. For instance, we speak not alone of structures and their logics, but structuration, a way of uniting process and structure (see Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality [1929]). Rather than hierarchy, we theorize heterarchies, i.e., several or many sites of hierarchy; we consider new ways of thinking about structures produced by aggregation and consider the logics of their formation. There are innovative ways of talking about imperialism and its financial mechanisms, and of colonialism and neo-colonialism. As well there are theory developments within world systems analysis. I say this to say that what are in effect Du Bois’s considerations of historical and social logics should be considered part of the developments in logics in science and social science. Hence what I am calling trialectics is a way to see and understand the historically constituted U.S. social structure; one that does not fit the binary of class and class conflict. Logic that must account for the complexity produced by slavery and white supremacy. Hence, the class and revolutionary processes in the U.S. proceed through logics of threes. Returning to the Black worker, he/she are both/and. It produces social complexity; however, the resolution of the class contradiction cannot occur without the resolution of the color line and cannot occur without the central and strategic role of the Black proletariat.

Most commentaries on Black Reconstruction are lacking. Part of the problem is most commentary comes from historians; philosophers, logicians, social theorists have said little or nothing about the work. This absence has impoverished readings and understanding and application of the work. Two of the limited approaches to the work are Eric Foner’s Reconstruction (1988) and a recent essay in The Nation magazine (May 3, 2022) by Gerald Horne. Neither understands its vast and profound implications. Of the work and its meaning in terms of contemporary social theory and practice, Foner returns to the earlier critique by James Allen in the 1930’s of Black Reconstruction. He ignores so much that is pregnant in the book, constituting a rebuttal through silence. Foner completely ignores the theorizing of class and class conflict, new logics of historical constitution, etc. It takes away from the work its attempt to understand revolution and the revolutionary process. Horne does the same thing, suggesting the work might be antiquated and proposes it fails due to its failure to consider settler colonialism and failure to look at Reconstruction through the eyes of Native Americans. For Horne there is no great theory, no disruption of logic, no meaning for class and class struggle and the revolutionary process in the U.S. It is Marxist, he says, but what does that mean? Does Du Bois dogmatically repeat Marxist formulations or does he use Marxism dialectically to produce something new? Is this an innovative work or is it a mere recounting of history from a Black person’s standpoint?

Recent political discussions centering on patriotic socialism and MAGA communism seem to not even know the work exists. In their rush to celebrate the white working class, they have completely erased the Black proletariat. It seems unknowingly their theorizing is overdetermined by whiteness and white identity. As such their politics have no way to think of ways out of the current crisis; let alone a path to revolutionary democracy and socialism.

CONCLUSION

Finally, even as we consider the necessity of a new revolutionary synthesis, I believe it fair to say the dynamic part of the synthesis, especially for this moment in U.S. history, is Du Bois’s theorizing. His thinking clarifies the paths towards democracy and revolutionary change in the U.S. His thinking lays bare what are the conditions and possibilities of a Fourth American Revolution. The emergence of a new and revolutionary Left depends upon understanding the vital necessity of a new revolutionary synthesis; a Du Boisian Leninist synthesis and a Fourth American Revolution.

Leave a comment