Presentation given November 6th, 2021 at the symposium “Strategy for Freedom: The Life and Vision of Henry Winston,” organized by the Saturday Free School

In 1904, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in his Credo to Darkwater: “I believe in the Prince of Peace. I believe that War is Murder. I believe that armies and navies are at bottom the tinsel and braggadocio of oppression and wrong, and I believe that the wicked conquest of weaker and darker nations by nations whiter and stronger but foreshadows the death of that strength.” We live in a time when the prophetic significance of these words is clearer than it has ever been before. The crisis of the west, and its redoubled efforts to maintain by any means its dominance over the world, makes it imperative for us to talk about peace today. Peace is and has been the most natural yearning of humanity since antiquity, the emphasis of every great civilization. The struggle for peace is the struggle for life itself. And yet, any strategy for lasting peace is incomplete which does not include an analysis of imperialism and its attacks on the very basis for peace.

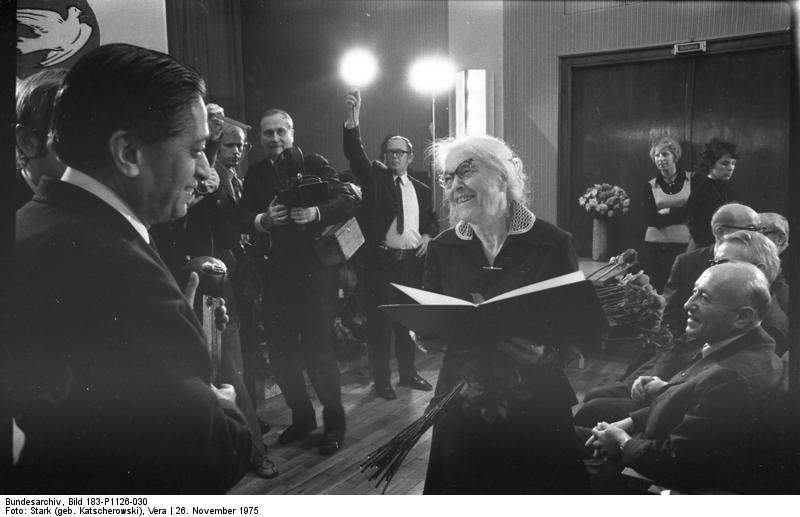

That is why as we commemorate the life and legacy of Henry Winston, we also remember his longtime friend and comrade Romesh Chandra, one of the greatest peace makers the world has ever seen, as an important figure for us to know and study today. Romesh was an Indian communist who participated in the national struggle for freedom and was at the forefront of the Indian Peace movement. He was one of the most important leaders and theorists of the World Peace Council, serving as its General Secretary from 1966, and as President from 1977. Before Romesh, the world peace movement was primarily a European affair, limited to governmental organizations and intellectuals. Romesh’s great contribution was that he broadened the peace movement by taking it to the masses, and fortified it by adding to it an analysis of imperialism. He believed that peace is everybody’s business, it is something to be built and not just defended, and the people have the agency turn the tide against imperialism and war. Under his leadership the World Peace Council became the general assembly of the peoples of the world and undertook the massive task of building a new world free from war and suffering, from exploitation and poverty, so humanity could move towards a higher stage of self-realization.

For Romesh, the world peace movement was the logical successor of the Indian freedom struggle, in which the people of India freed themselves from the yoke of two centuries of colonial oppression through the principles of nonviolent resistance. He emphasized the inseparable link between the peace movement and the struggles for national liberation in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Romesh was deeply influenced by Lenin and his commitment to unity in the struggle for peace. He would say, “One day after the Soviet Union was founded, Lenin signed the Decree of Peace. From that moment on it became clear to the whole world, that now there existed a power, a government, which based its entire foreign policy not on aggrandizement, not on expansionism, not on war, but on peace and on willingness to sacrifice for peace.” For Romesh the Soviet Union was “the bastion of the world’s struggle against imperialism,” Lenin’s most precious gift to mankind. Along with the World Peace Council, the Soviet Union and other socialist countries like Cuba stood beside every struggle for national liberation and peace in the developing world.

The World Peace Council defined positive peace as not just freedom from the cost and degradation of war but as a prerequisite for the development of human potential to its fullest extent. This was also Rev. Martin Luther King’s formulation of positive peace. Besides political independence, the struggle for peace was also therefore a struggle for development, for economic independence, and for the sovereignty of each country over its natural resources. Romesh asserted that there was hunger and poverty in the developing countries because they were robbed and plundered by neocolonialism, and not because of overpopulation and backwardness, which was the racist theory peddled by Imperialist powers. He emphasized that the wealth of each nation must remain in the hands of its people, and not in the hands of imperialists and monopolists, saying, “Peace is oil in the hands of the people whose soil produces this oil, Peace is copper in the hands of the people of Chile.” The World Peace Council’s struggle for positive peace included fighting for a New International Economic Order, which gave to each country the right to nationalize its resources, set fair prices and tariffs, and control the activities of multinational corporations on its soil. Romesh would say, “We seek to bring down the cost of living and to raise high the price of life — so that one day bread can be free and life so precious that no man shall ever buy another man’s life.”

Romesh understood that the strength of the struggle against imperialism and for peace lies in the unity of all peace-loving peoples, of all democratic and anti-imperialist forces in every country. He believed that the peace movement could not be compartmentalized, and that the progress and advance of one people could not be separated from that of all others. Under his leadership, the World Peace Council extended its support to the Afro-Asian Solidarity Organization, the Organization for African Unity, and the Non-Aligned Movement. It agitated against military bases of the US, France, and Britain in the Indian Ocean, demanding that it remain a zone of peace, contributing to the welfare and growth of every country. It stood with the Vietnamese people’s struggle against US aggression, the struggle of the people of Palestine against Israel, and the struggle of the South African peoples against apartheid. Romesh would emphasize again and again that the Imperialist countries which were behind these heinous attacks on darker humanity, did not have the support of their own people, who yearned for peace. In particular, the Vietnam war galvanized the peace forces in every country of the world. In the United States it inspired millions of citizens from all sections of society to join hands in demanding peace and social transformation for the masses. The US peace movement provides hope for our times about the possibilities for unity and brotherhood that can materialize, even at the very epicenter of imperialist forces, when a people come together in the defense of justice and humanity.

The gains of the peace movement were jeopardized by the virulent anti-communist policies of the United States, which had emerged as the foremost imperial power after the end of the second world war. The threat of nuclear war between the US and the Soviet Union made world annihilation a very real possibility. In the US, anyone who raised his voice for peace was indicted as a communist or communist sympathizer, and often incarcerated or executed. Figures like Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Henry Winston, and King were all targets of this anti-communist hysteria during the McCarthy era. This would lead Du Bois to say, “Blessed are the Peacemakers, for they shall be called Communists. Is this shame for the Peacemakers or praise for the Communists?” Ironically, while talking about defending the freedom and democracy of newly liberated nation, the US ruling class unleashed one of the most violent attacks on democratic and civil liberties at home. Furthermore, it sought to obstruct the growing unity among the peace-loving peoples of Asia and Africa and led a campaign to weaken the friendship between them and the Soviet Union and other members of the socialist bloc.

Romesh understood, as Baldwin did, as Rev. James Lawson did, that anti-communism stems from the ideology of white supremacy, which presumes that the whole world should want to become white and subscribe to the white ideal of democracy, however divorced it is from the general upliftment and welfare of the masses. It stems from the racism that lies at the very heart of Western imperialism and its threats to peace. Romesh saw that racism and racial discrimination were not just crimes against humanity, they help to create the very basis for war. The meaning of this becomes clear when we consider that every war fought (and lost) by the US in the last 70 years has been in Asia. If US soldiers could burn little children with napalm in Vietnam, it was because they had been trained in racism, trained to despise the Vietnamese people, to consider them less than even animals.

In the Du Boisian tradition, Romesh, like Winston, strove to bring to world attention the significance of the color-line in the struggle for peace. He recognized, as Winston did, the centrality of the black freedom struggle in the broader world movement for peace and justice, that included the anti-colonial struggles of Asia and Africa. The Civil rights movement was the moral vanguard of the forces for peace and against imperialism in America, with King calling for a positive peace that did not just mean the absence of tension but the presence of justice. Romesh stood with the Civil rights movement and called for unity and solidarity between the fight against racism in the US and that in southern Africa. He also understood that the struggle for peace was as important for the white people of the United States as it was for the blacks, because the stockpiling of arms and weapons of mass destruction for racist wars abroad, worsened the economic crisis at home, leading to widespread unemployment, inflation, and poverty. He called for unity of the working class across the color line, for solidarity between the black freedom struggle and the white workers who “have nothing to gain and everything to lose, if this racism and racial discrimination is allowed to be continued.” This is extremely significant for our times, as we watch the US ruling class attack the suffering and discontented white worker and attempt to frame him as the real perpetrator of racism and white supremacy.

King emphasized the inseparable link between racism and war when he said, “One cannot be just concerned with civil rights. It is very nice to drink milk at an unsegregated lunch counter — but not when there is strontium 90 in it.” The US ruling class looked upon King with patronizing tolerance as long as he was non-violently fighting for racial equality. However, in that decisive moment of his life when he connected the fight against racism and injustice to the fight against poverty and war, he became a threat and had to be eliminated. King’s true legacy is that of a uniter of people, of the forces for peace and justice against the forces of war.

Romesh would point out that the ideology behind the treatment meted out to King was the same behind the attempt to distort the legacy of another man whom King greatly admired, Mahatma Gandhi. He noted that Gandhi was diminished and portrayed by the imperialists as “something of a crank, someone who believed in peculiar things like non-violence and who dressed in a peculiar way. What they sought to hide from the peoples of the world was the true image of Gandhi as a fighter against imperialism, against poverty, against racism and war.”

Romesh warned us of another way western imperialism conspires to dilute the connection between racism and imperialism, by creating the false impression that racism exists in every country of the world. In recent times we have seen intellectuals with colored faces and white voices being authorized to speak the language of the ruling class on race. The attacks on Gandhi, on India and its anti-colonial struggle are concrete examples of this conspiracy. Romesh also warned us against Imperialism’s attempt to confuse world opinion about socialist and communist regimes on the pretext of championing human rights. In recent times, we have also seen the US ruling class attack communist countries striving for the self-actualization of their people, as authoritarian and undemocratic, while failing to provide for American citizens the most basic human rights. We must ask, is poverty and hunger a human right? Is debilitating addiction and crime among the youth a human right? Isn’t the right to work and live a life of dignity a human right?

Romesh Chandra is a figure for our times. The concepts he and the World Peace Council developed in the struggle for peace are as relevant to us today as when they were formulated. We stand at the brink of a monumental shift in world powers. The crisis of the West is a crisis of imperialism. The people of the United States are rising in revolt and challenging the legitimacy of a ruling class that favors wealth and profit over human beings. The rise of China and the shift to a multipolar world order is seen as an existential threat by the American ruling class. Like a cornered beast it has resorted to desperate measures. We are seeing the creation of the objective conditions for a new cold war. This is a time for introspection on the past, a time to seek ideological clarity. We must engage in a deep study of the life and legacy of Romesh Chandra and reinterpret it for our moment. We must seek a new economic order with humanity at the center of its concern, and carry on the struggle for peace, which is not yet complete.

Lastly, we must view as Romesh did, the struggle for peace as our moral obligation to the children of the world. What world will we leave behind for the immortal child of today, tomorrow, and the future? Romesh would say, “Children represent life, children deserve a fullness of life, they deserve beauty and the light of knowledge, they deserve to look around themselves and feel optimistic about the future. Joy and happiness are their birth right.” We cannot give our children their birth right in a world which is at war, where famines created by man take their life away before it can blossom. In a climate of deep ideological confusion and moral poverty, we cannot give our children such meaningful education that they might grow up to be men and women who can lead the people in the forward march of humanity. Our struggle is the struggle to build a world where children can realize their true potential, where their imagination and talents are not fettered by poverty and hunger and racism, where they can grow up surrounded by beauty and goodness and truth. For our children we must pledge as Romesh Chandra pledged, that “we shall not rest until we achieve what Du Bois aimed to do, what Paul Robeson aimed to do, what all the great leaders of the liberation struggle everywhere aimed to do: we are going to create the kind of world in which all children shall play and in which no child will be burned by napalm, no child will go hungry, no child will be thrown into the ghetto, and in which all children will know what a sweet tastes like.”

Leave a comment