By Archishman Raju.

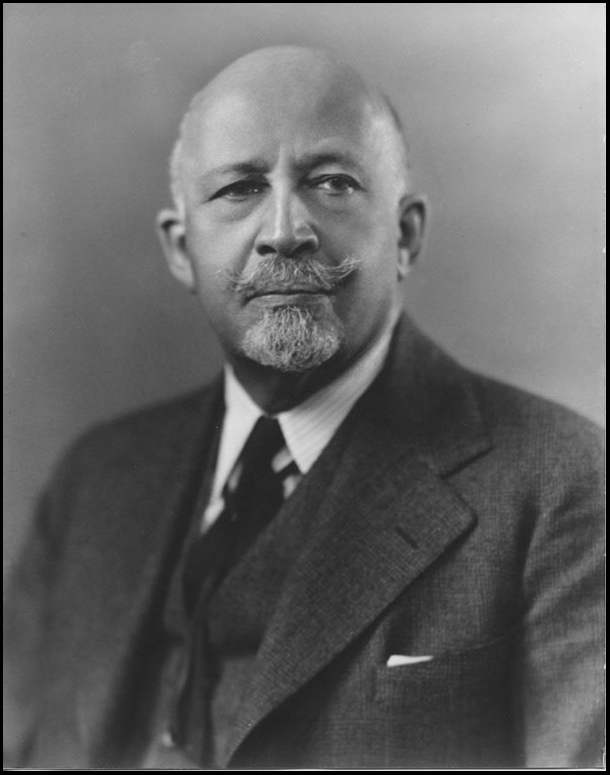

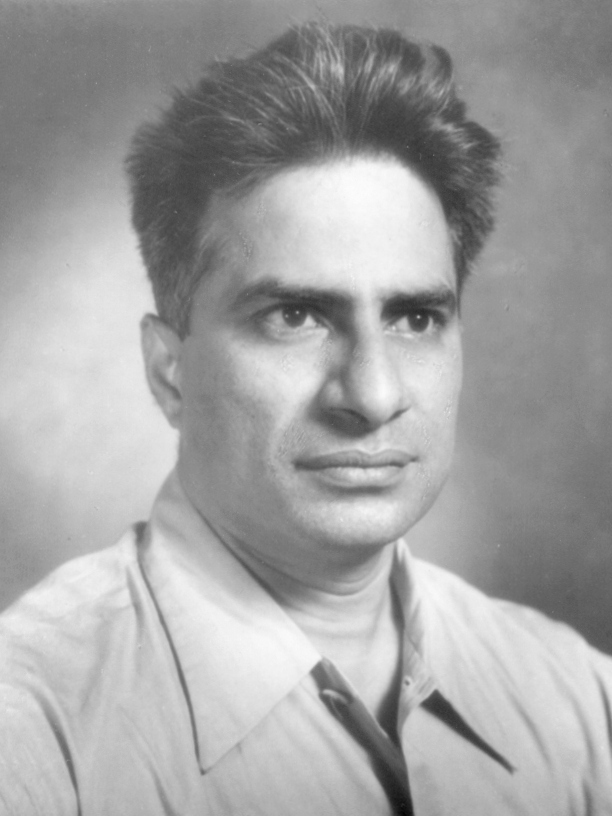

In 1949, the Indian scientist D. D. Kosambi visited the United States for a conference on peace, commenting “I saw that American scientists and intellectuals were greatly worried about the question of scientific freedom, meaning thereby freedom for the scientist to do what he liked while being paid by big business, war departments, or universities whose funds tended to come more and more from one or the other source.” He condemned the witch-hunts taking place in America of fighters for peace and communists under the name of “democracy” and “freedom”. Another participant at the conference, W.E.B Du Bois was one of the targets of this witch-hunt and spoke at the conference on the nature of freedom. We are “on the threshold of infinite freedoms”, he said, if only we can overcome the barrier of war and ignorance. Both Du Bois and Kosambi advocated for a scientific understanding of the world, which would in turn allow true human freedom. Both considered the struggle for peace to be central in the ultimate fight for freedom. Their ideas are deeply linked by the common historical struggle against racism and imperialism that they were a part of.

W.E.B Du Bois and D. D. Kosambi are two great scientists whose contributions are essential to include in any scientific understanding of society. Du Bois, trained in history and sociology, was the first to conduct a scientific study of race in American society. Kosambi was trained in mathematics but was the first to conduct a scientific investigation of ancient Indian history in modern times. In considering and giving proper place to the agency of African and Indian people and civilizations, they made an epistemological break with European social science. Furthermore, their theoretical understanding was linked to the concrete struggle that they participated in: a struggle against a white supremacist world system which manifested as racism in the United States and as colonialism in India. Neither was given any prominence by western universities or western academia during their life-time, and yet it was their rootedness which allowed them to produce the profound understanding of a revolutionary science. As great as their contribution was to the time they lived in, it is to our time that they offer an invaluable message and direction.

The Epistemological Crisis of the West

The western world finds itself today in a total crisis. While the crisis has economic, political and psychological dimensions, it is also an epistemological crisis, with an ever growing divide between the elites and the masses of people. What the elites arrogantly dismiss as ignorance of facts and disbelief in science is, in fact, the presence of different modes of reasoning and a mistrust of mainstream institutions among the masses of people.

This epistemological crisis also affects the institutions of knowledge themselves. As Gideon Rachman argues in the Financial Times, the American Dollar and the American University are the two measures of western power (to which we may add the American military). The American University is thus at the forefront of this white supremacist world system. It is profoundly influential in determining the ideological landscape, not just in America, but around the world where westernized elites tend to be in positions of influence and power. Moreover, such westernized elites tend to share certain historical understanding and modes of reasoning imparted through the education system. In our present crisis, their epistemology stands helpless in the face of current day events for it finds them incomprehensible.

Neither Kosambi nor Du Bois had a high opinion of the western university. As Du Bois said, “We still have large college and university facilities, but the entering students are poorly equipped and with limited ideals and objectives. The professors are today increasingly afraid to study and teach the social sciences, so that history becomes propaganda; economics hides in higher mathematics and social study is limited by military objectives. In the physical sciences our objects have become limited mainly to weapons of war.”

This description fits the current situation well. Students suffer from anxiety and depression and are offered little direction. The ideological landscape has become even narrower with professors tied to their careers and celebrity-hood. On one side is the positivist conception of knowledge, based on data and evidence which seeks to measure and control society but is overdetermined by war and profits. On the other hand, and of more recent origins, is the rejection of truth and science, the questioning of the European narrative of progress and universality done in a way that continues to uphold western domination. This side forms the basis of a “cultural left”, guided by pompous and irrelevant French thinkers with hundreds of thousands of citations but no revolutionary achievement to speak of. These thinkers neither presented any profound critique of white supremacy, nor found a way to transcend it in collective struggle that comprehensively addresses its material, ideological, and socio-cultural dimensions. They instead turned the focus to personal interactions and symbolic acts. This cultural left therefore indulges itself with an excessive emphasis on questions of language, body, identity and victimhood. Two images capture these two sides: on one side is the disinterested and highly paid scientific expert and on the other is the young gentrifier with a “Black Lives Matter” sign taking down statues. Both do not represent or mean much to the struggle of the masses of black poor and working people.

The epistemological crisis underpins the bankruptcy of this woke left and its resolution is central for the emergence of a new left, which seeks to be based in poor and working people and sees them not as victims but as agents of change, which is able to continue the interlinked struggle against war, poverty and racism. Such a left will need ideas which can only come from a study of past revolutionary thinkers; it will seek the truth for it serves the cause of freedom and in the process can uncover a scientific method which can understand our complex society seeking to change it. Among such thinkers, one must include W.E.B Du Bois and D. D. Kosambi.

A New Revolutionary Science

For Kosambi, science and freedom were deeply linked and in a dialectical relationship to each other. Building on the classic definition of freedom as the “recognition of necessity”, he defined science as the “cognition of necessity”. By science, he did not mean the authoritarian conception of scientific experts who serve the wealthy and contemptuously seek to explain to people who distrust them for good reason. Rather he had a democratic conception of science which was capable of changing the scene of its own activity. If scientific reasoning were applied to the conditions in which science was being done, the individual scientist would be forced to make a choice: whether to continue in an unjust system or pursue scientific analysis to resist the unjust system itself at the cost of safety, popularity and their career. Du Bois would eloquently talk about the moral choice before the scientist in his essay Galileo Galilei saying that Galileo’s lie to save his life had done more harm than all of the good that came from his scientific contributions. “Science is a great and worthy mistress”, said Du Bois “but there is one greater and that is Humanity which science serves; one thing there is greater than knowledge, and that [is] the Man who knows.”

Such scientific understanding could only come by a proper understanding of history, which they understood was not about the past but shaped the attitudes of the present. Both Du Bois and Kosambi challenged the white supremacist notions of history which did not see the agency of darker civilizations of the world, and believed that Europeans brought science and progress to darker peoples. They used the concept of civilization not to signify the apex but as resting on its broad base. As Kosambi was to say, “Anyone with aesthetic sense can enjoy the beauty of the lily; it takes a considerable scientific effort to discover the physiological process whereby the lily grew out of the mud and filth.” Kosambi argued that India had a history, despite European narratives which saw it as static and fixed, while Du Bois was to do the same for Africa in The World and Africa. This starting assumption of the agency of Indian and black workers was central to a new epistemology of knowledge.

This epistemology seeked to bring together the knower and the known, and saw people who had been declared to be “backward” and “ignorant” as capable of and important to scientific knowledge. As Du Bois said, “I am bone of the bone and flesh of the flesh of them that live within the Veil”. Kosambi would say in the same spirit, “The material, when it is present in human society, has endless variations; the observer is himself part of the observed population” and therefore the study requires “constant contact with the major sections of the people”. He realized that proper scientific knowledge would require “combined methods.” The study of the Indian peasantry, for example, could not be accomplished by a single discipline, but only by combining linguistic, sociological, archaeological, anthropological, and historical insight with field studies.

Both saw scientific knowledge not as deterministic but as probabilistic. Du Bois said that science involves both law and chance i.e. science studies regularities in nature and society but does not determine completely the scope of human action. The development of human society was constrained by objective processes but the outcome of these processes was not determined in advance. Society could not be understood as a whole by removing all reference to the human being.

In dedicating the purpose of science to freedom and to humanity, the majority of which was composed of yellow, brown and black labor, the science they conceptualized was not an “objective” science which seeked disinterested knowledge but rather a science that involved intimate contact with the people, that was partisan for it stood in favor of the oppressed.

This partisanship to the oppressed meant that they both saw the oppressed as closer to the truth than the elite. Hence the process of scientific discovery would not be from above but with and among the people, it would be concerned not simply with regularities of nature but with actual deeds of living men. The true test of science was practice. It was not simply concerned with understanding the world but also with changing it. Only knowledge that served in practice to liberate the oppressed in practice and take us towards greater freedom would constitute a true science of human society.

Struggle for Peace and the Way Forward

Their life struggle against the white supremacist world system brought both Du Bois and Kosambi to view the struggle against white supremacy, and the struggle against imperialism as linked to the struggle for peace. Kosambi said “Science and freedom always march together. The war mentality which destroys freedom must necessarily destroy science. The scientist by himself can neither start nor stop a war….But a scientific analysis of the causes of war, if convincing to the people at large, could be an effective as well as a democratic force for peace.” Du Bois was to theorize the relationship between peace, democracy and color in his book Color and Democracy. He pointed out that what Europeans had been calling peace-time was in actuality a continuous series of wars against the colonized countries, and colonialism was the root cause of major wars. To link Du Bois and Kosambi together is to see the link between the anti-racist struggle and the anti-colonial struggle, as well as the struggle for peace which is central to dismantling and transcending the white supremacist world system.

The struggle for peace is a precondition for the struggle against oppression of all kinds. It is our historic task to continue this struggle for peace and against the white supremacist world system. Our struggle requires a new epistemology and a revolutionary science rooted in the great mass struggles of the 20th century. For this, we must study the thinkers who organically participated in them.

A revolutionary science must take the task of understanding our complex world seriously. It must seek to democratize science, giving it a broad base and taking it away from the institutions of the elite which are beholden to the wealthy and the war-makers. It must go away from white supremacist notions of universals and progress but it must not abandon the notion of truth and history. It must see black and brown workers in particular and the working class as a whole as agents of historical change and the leading force for democracy and peace in the world.

Doing so will free science from the clutches of war, and lead to the much greater freedom that Du Bois imagined. If such an effort is successful, then it can lead to development of new ideas in service to humanity, away from the ego-centric nihilism of our present-day universities. In the U.S., this must mean at our present time the establishment of new spaces of knowledge creation which base themselves among workers and seek ideas which are able to free humanity.

Leave a comment