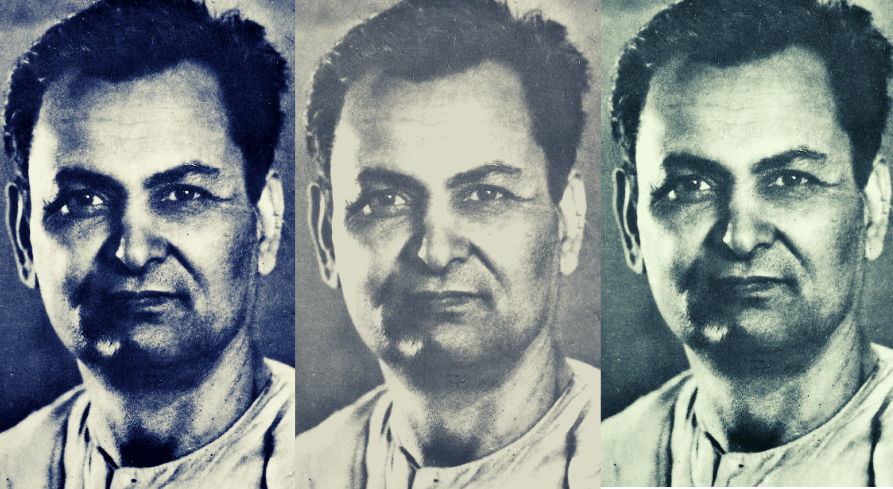

By Rahul Sankrityayan.

Introduction: This piece about the ancient relations between China and India was written in 1950 after the culmination of India’s freedom struggle and the Chinese Revolution. It is written by one of India’s greatest scholars, Rahul Sankrityayan. It describes a civilizational complex of which India and China were a part. The names of a few Chinese travellers to India are well known but this piece gives details on the constant contact and mutual exchange. Buddhism was the main way in which this relationship was forged but the relationship extended far beyond religion. Today is a time when we must return to this great civilizational relationship between these two Asian countries to forge a new unity and peace. Below are excerpts from the piece published in full in Selected Essays, Rahul Sankrityayan, Peoples Publishing House (1984).

India and China are two great countries of Asia. They have left not only a lasting mark on several parts of Asia by their culture, but have also affected economic development. In several countries they divided up their sphere of work. Tibet was a country of nomads till the seventh century. Both countries had an equal share in initiating Tibet into civilisation. There is the stamp of China everywhere in Tibet, their ways of life, clothes, their courtesy and polite ways, at the same time India has deeply influenced her language, literature, script, sculpture, paintings and spiritual life, India was successful in achieving all this without distorting national Tibetan forms; this was in keeping with India’s age-old tradition. Tibet had been almost a part of China for the last thirteen centuries.

Contact between India and China took place on a level of equality. When these two countries came into contact, both were considered to be advanced countries of the world. The contact between India and China is a model example of what cultural intercourse between two neighbouring countries should be. India also learnt a number of things from China, among which the chief is silk, weaving and embroidering. Indians used to call silk Chinanshuka, that is, China cloth. It is not our purpose to detail here what China gave to India, but to remind Indians that the sympathy and goodwill of India for new China is not a new phenomenon. There is incontrovertible historical proof that these relations were placed on a firm foundation two thousand years ago; their beginnings were made even earlier.

…

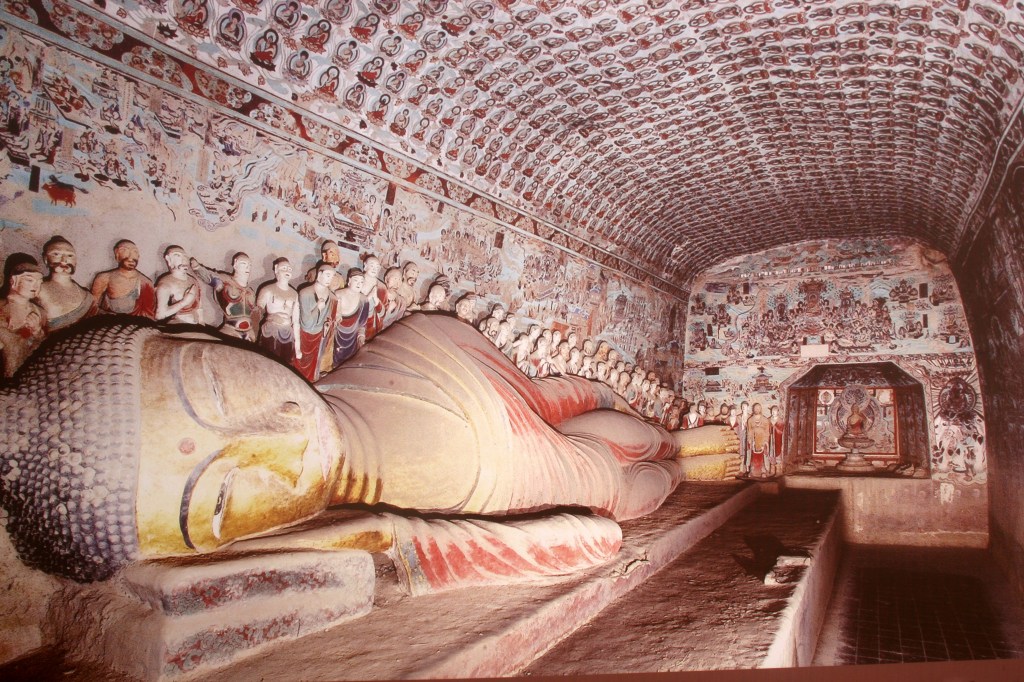

India and China established cultural contact through Buddhism, but neither Buddhism nor any other religion propagates its creed in a country through theology and ritual alone, nor can it be very successful in its mission if it does so. That is why a missionary of religion carries along with him the art, literature, philosophy and numerous other cultural contributions of his country. India too during the golden period of its cultural advance gave to various countries of Asia not only the Buddhist religion, but also its arts, script, literature, etc. to enrich their cultural life. In Eastern-central Asia (Sinkiang) the Indian script was current at one time. The scripts of Burma, Siam, Cambodia and Tibet are even today developed versions of the Indian script, and use vowels and consonants resembling ours in sounds and in the same order. China had its own script and India did not have to transport its own script there. In art and literature too, China was not a backward country, but it was willing to learn from India. The beautiful sculptures and paintings of Tun-Huang and other places in the fourth and fifth centuries after Christ are indicative of this. The works of our great writers Ashvaghosa, etc. having been translated into Chinese, enriched the literature of that country and gave it versatility. Two great translators of Indian books, Kumarajiva and Hiuen-Tsang are considered to be the great masters of Chinese language and literature.

The arrival of Buddhism

Buddhism had certainly reached China during the reign of the Han dynasty (25-220 AD). Emperor Ming-ti (58-75) of this dynasty was a friend of Buddhism. It was considered necessary to relate everything to kingship during the ages of monarchy, otherwise it was not possible for Buddhism to have entered China in the middle of the second century before Christ, when Chinese influence began to spread in Sinkiang. By 111, the whole of Sinkiang was in Chinese possession; here, Buddhism dominated the scene for ten to twelve centuries. If the Turkish Emperor Toba (56-80) and his subjects could be influenced by a single Buddhist war-prisoner, it cannot be possible that lakhs of Saka and Hun Buddhist war-prisoners who came into China, did not leave any impression of Buddhism on the Chinese people. The conversion of Ming-ti only meant that Buddhism now came to be respected among the Chinese feudal class also. Ming-ti sent out representatives to bring back with them Buddhist religious books and monks. It was with these that two Indian monks, Kashyapa Matang and Dharma-Ratna, came to China with Buddhist religious books in 67 AD. The oldest translation of an Indian book into Chinese was made by Kashyapa and is available even now. Ming-ti gave a great welcome to these monks, as they entered his capital, Loyang, riding white horses, and he built a monastery, Pei-Ma-Ssu (Shwetashva Vihara) for them. Kashyapa was a resident of Madhya Mandala. In Buddhist works the country between Kurukshetra and the Santhala Parganas and between the Himalayas and Vindhyachala, that is Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, is described as Madhya Mandala. Kashyapa was the master of the Southern Hinayana School. He had gone to South India on a religious mission. His companion, Dharma-Ratna, too was a scholar from Madhya Mandala. Kashyapa and Dharma-Ratna had translated other works too, but they are not available. The service rendered by the two through their studies, teaching conversations and meeting people, was very helpful in bringing China nearer to India.

In the sphere of literature, serious works begin eighty-one years after Kashyapa, when Parthian scholar Anshi-kao (148-170) reached China. Iran was under Parthian rule at this time. Both the Sakas and the Parthians came from the ancient Saka people, who later on produced the Slav tribes of Eastern Europe. An or Anshi is the Chinese word for Parthian. About Shih-Kao it is said that he gave up his kingdom and donned the yellow robe. Like Kashyapa he came via the Central Asian route and reached the Chinese capital Loyang in 148. He stayed in the Shwetashva monastery. In his twenty two years of stay in China he worked untiringly to introduce Indian thought to Chinese scholars. To Anshi-Kao goes the credit of placing Buddhism on a firm foundation in China. He also strengthened the cultural relations between the two countries. Of the ninety-five books translated by him, fifty-five are available today. During the Han period China had made all round progress. China expanded both politically and culturally during this period. She made good progress in all directions, literature, art, new inventions etc. Indian Buddhism made its own contribution to this progress. Other translators and missionaries of this period were the Indian Mahabala (Chin-ta-li) and Dharampala (Than-kao), and the Tadjis Kang-chu and Kang-mang Hsiang. During this period Indian thought and culture received such a warm welcome in China that more scholars came from Khotan, Sogdia (Tadjikistan), India and Lanka to participate in this work. In China the teachings of Confucius were the most forward in support of the feudal lords and were widely current; they had no deep concern with spirituality. In the teachings of Tao there was mysticism, but it had greater indifference towards this world. A contemporary Chinese scholar explains why Chinese thinkers were drawn towards Buddhism: “Confucius teaching has no answer to give to the most serious problem of existence. It can give man neither strength in the life-struggle nor solace at the time of death.” Our Indian representatives were ever prepared for a synthesis and compromise with the Chinese thought. In the second century there was a famous Buddhist scholar, Muchu, in Southern China. His opinion was this: “Confucianism might be the religion of kings, but Buddhism is the religion of the people. The teachings of Buddhism are not against the ancient Chinese religious thought. Their ideas are the same. It is possible for an individual to conform to both. If Buddhist ideas are accepted along with our own noble thoughts, it would be good. A wise man accepts good things, wherever they may come from; he is prepared to accept teaching from others.”

Fa Hsien

Indian missionaries were not alone in carrying in the task of strengthening relations between India and China. Many Chinese also helped in this work. The travels of Fa-Hsien, Hiuen-Tsang and I-Tsing not only brought India and China nearer, but their travel accounts are priceless treasures for Indian history. It is regrettable that our writers did not make our people as well acquainted with China, as Chinese writers made their people with India.

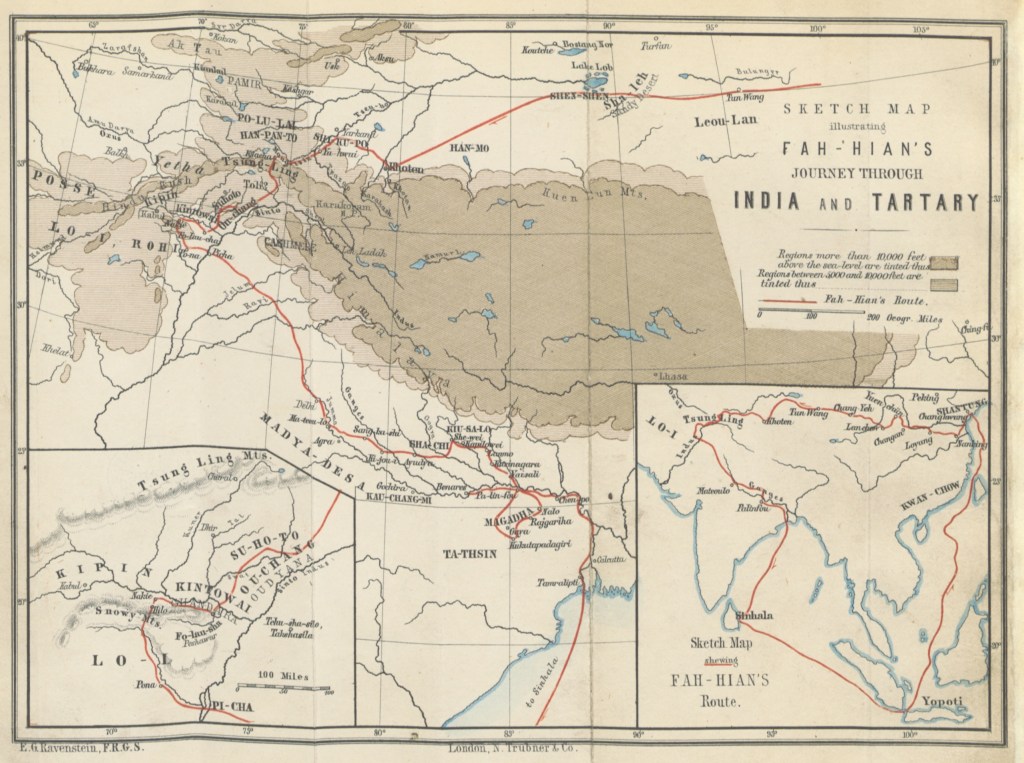

Fa-Hsien was the first Chinese pilgrim to reach India. Other Chinese traders may have come earlier than this, but they have left no records of this. Towards the end of the fourth century the Gupta Emperor Chandragupta Vikramaditya ruled over most of the country. This was the age of Kalidasa. This was the golden age of Indian culture. It was at this time, in 399, that a party of Chinese youth started for the first time on a pilgrimage to India, the centre of Buddhist culture and religion.

Fa-Hsien was the leader of this party. He spent fifteen years, from 399 to 414 in his travels in India and obtained a very deep understanding of Indian life. Fa-Hsien was born in the modern region of Shanshi. His parents had initiated him into Buddhist orders in his childhood and put him in a monastery. He was very fond of studying the Buddhist law, Vinaya, but these books were rare in China in those times. He left the capital, Chang An in 399 to make these scriptures available in China and to visit the holy places of India. He took the Central Asian route and passing through the deserts, reached Turfan. He arrived in Khotan after experiencing great difficulties, taking thirty-five days days to cross the deserts of Takla Makan. Khotan had been Buddhist county for the last four centuries. There were fine students and teachers of Buddhist scripture here. From Khotan he reached Kashmir after traveling fifty four days; then passing through Punjab and visiting various holy places, he continued his study of sacred Buddhist texts. Nalanda had not yet acquired its later fame, but there were similar other viharas. On his return journey he took the sea-route via Ceylon and Java. Fa-Hsien died in South China at the age of eighty-six. He translated many Buddhist works which were valuable not only for the Buddhist religion, but also for Indian history. Praising the travels and courage of Fa-Hsien, his translator Gibbs writes, “The travels of St. Paul pale into insignificance when compared with those of Fa-Hsien.” Fa-Hsien himself writes while concluding his travel records: “When I look back and recall what situations I have had to pass through, my heart is agitated and I begin to sweat. I faced such dangers, passed through so many dangerous places without any consideration for myself without hesitation; I could do all this, because I had a definite aim before me…I had carried myself to a point, where death seemed almost certain, but I was prepared for all this if I could achieve even one-ten thousandth part of my aim.” The courage of Fa-Hsien was amazing; his name will always be remembered in our country with respect and gratitude. This is certain. But we must also remember we had our own Fa-Hsien: Kashyapa Matanga, Dharmapala, Sanghavarma, Dharma-Raksha, Sanghadeva, Dharma-Ratna, Kumarjiva, Gunavarma, Gunabh, Paramartha, Gautama, Gyanaruchi, Jinagupta, Divakar, Shikshananda, Bodhiruchi, Amoghavajra, Dharmadeva, Danapala who went to China, and Jinamitra, Dana-Shila, Santa-rakshitas, Kamala-shila, Smriti-Jnana-Kirti, Dipankara Srijnana, Gayadhar and Sakya Sridhan who went to Tibet, did not face fewer difficulties. Their work was no less important, but they have left no record for us of their travel-dangers and sufferings and eye-witness accounts of the countries they visited. The reason for this may be an indifference towards these things in our country. But these bones scattered in Loyang, Chang-An, Nan-king and many other places in China constantly arouse this feeling in our heart that we cannot allow their work to die out.

After Fa-Hsien, a regular band of pilgrims came to India from China. Among the pilgrims who arrived in India in 516, there was a former queen of the Wei dynasty. In 518, there came Sung-Yung, a lay brother, with many companies and a monk Hui-Chen, on a pilgrimage to Gandhara by the Central Asian route. This country was ruled by the Turks at this time and they were greatly under the influence of Buddhism. In 522 Hui-Chen returned to China with 170 books. The original travel account of this pilgrim is not now available, but we still come across many of his statements quoted by others in 547. There was rivalry between the Confucian, Tao and Buddhist religions till the fourth century, but attempts began with the fifth century to make a synthesis of the three religions. An influential feudal lord of South China, Chian-Yuh (447-97) said on his death-bed: “Give me Confucian books in my left hand and Buddhist scriptures in my right hand.” Another famous scholar, Fu-Shi (497-579) always wore a Tao cap, Confucian shoes and a Buddhist shawl round his neck.

After the Sui dynasty, the Tang dynasty (618-907) continued its work preserving the unity of China. It was at this time that the famous Chinese pilgrim and scholar Hiuen-tsang came to India. In the opening years of the Tang dynasty the Buddhists were cruelly suppressed. The property of many monasteries was confiscated on the charge that the Buddhists made people indolent and a large number of monks and nuns were penalised. In these circumstances Hiuen-Tsang considered it best to leave his country and go to India. In 629 he started for India by the Central Asian route and returned to his country after 16 years in 645. By this time the oppression against the Buddhists had ended and the famous pilgrim was honoured greatly on his return to hom. Hieun-Tsang started writing an account of his travels. The second part of the travel accounts was written by a disciple of Hiuen-Tsang and a biography of the great traveller was completed by his two disciples in 665. Hiuen-Tsang translated 75 serious works from Sanskrit. He had studied for many years at Nalanda. He was very intimate with Indian scholars and regularly corresponded with them. Hiuen-Tsang had written a letter to his friend Jina Prabha who had returned to India after some years stay in China. A Chinese translation of this letter originally written in Sanskrit is still in existence. Here are some extracts from this letter:

“A few years ago when the ambassador returned, I learnt that the great Acharya Shil Bhadra is no longer alive. I was plunged into great sorrow, when I heard this. Oh! In this ocean of grief the ship sank. The eyes of gods and men were dimmed. Is it possible to express the pain caused by his setting China? In ancient times, when Pragya (Buddha) withdrew his light, his great work was advanced by Kashyapa. When Shanbhasa departed this world, the good law was revealed by Upagupta. And now… when the leader of our faith (Shil Bhadra) has achieved true glory (Nirvana) the Acharya of our religion will have to fulfill their duty in his turn… of the scriptures and the commentaries I had brought with me. I have almost completed the translation of about 30 volumes… In a boat accident on the Sin-tu (Sindhu) I lost a bundle of manuscript. The undermentioned books were destroyed in this accident. If possible, please send them to me. I am sending you a few things as gifts. I request you kindly to accept them.”

Acharya Shil Bhadra was the kulapati (head of the community) at Nalanda. At this time ten thousand students and teachers were also in residence at Nalanda. Shil Bhadra was the teacher of Hiuen-Tsang also. The letter of Hiuen-Tsang reveals how intimate were the relations between Chinese and Indian scholars at that time.

Buddhism has been the link between India and most of the outside world. This relationship began to decline with the destruction of Buddhism. Our subjection also helped to weaken memories of such cultural relationships. After centuries India is again today in a position to revive these ancient cultural relations.

From what we know of the ancient cultural relations between India and China, we learn that our ancestors had done much to strengthen fraternal relations between two countries. Today new China is creating a glorious, new economic, cultural, political and social life for herself. Our country is watching her with great sympathy, regard and curiosity. There is no doubt that the experience of China will be a beacon-light for us, and it is natural and desirable at such a time for our thoughts to turn to the sacred memories of our ancient relations.

Leave a comment