By Eunnuri Yi.

Paul Robeson wrote that people who have lived in a state of inequality, who felt their status barred them a complete share in all that the world has to offer, often want nothing more than to prove their equality with the white man “on the white man’s own ground.” He went on to say that “Only a few will recognize that the very impulse which drives them to copy those with the desired status, is killing what is most of value — the personality which makes them unique.”

Koreans and Korean Americans today face a choice: whether they will ground their cultural identity in unprincipled traditions dictated by the West, or if they will turn to the traditions of the people who have built Korean civilization — the workers and peasants that give Korean culture both its uniqueness and its connection to humanity. The legacy of the diasporic figures Baek Seok, Ahn Chang Ho, and Han Se-Gwang, who found beauty in the poor, identified with the black freedom struggle, and participated in the world struggle for peace and justice, can be a bridge for Koreans to understand their place in the world today and the task before them.

American Imperialism and Korean Cultural Export

The history of K-Pop can’t be reduced so simply to an imitation of whiteness or American culture, but it is surely part of the psychological attitude of many who embrace Korean pop culture in the West. Moreover, the role and effects of American imperialism on the Korean peninsula in the last 75 years cannot be overemphasized. The Western influences that K-Pop has accepted, assimilated, and adapted have explicitly come out of this military occupation, as the American Forces Korean Network (AFKN) broadcast and U.S. Army clubs in the surrounding camptown area of Itaewon exposed American music to the mainstream.

Abstractly, K-Pop may appear to be a mere product of cultural exchange, or a fusion culture attractive in its hybridity to Westernized or Americanized Koreans. Yet concretely, this cultural exchange is fundamentally shaped by the military occupation which makes South Korea a neo-colony, reliant upon exporting a culture to satiate the rest of the Western and Western-seeking world. Its aesthetics and themes are based on hyper-capitalism, grounded in competition, limitation, and yearning mixed with rage.

This culture encourages intense consumption and competition as a way of life through an emphasis on virality, advertisements, merchandise, and a fervid fan culture which encourages both escapism and obsession. Korean popular culture is so digestible and intelligible to Westerners because it portrays a Korean society similarly nihilistic in attitude as the West, with twists of fanciful or technical novelty. It accurately depicts both despair and conflict: the ugliness of a society built on a foundation of division and exploitation; the ugliness of a world in which young people grow up rebellious and hateful, not knowing how to love themselves; human beings struggling hard to find even a remotely human or loving way of life.

Even as the K-Wave becomes a lucrative cultural export, it seems meant for nothing beyond the accumulation of greater capital. Even critically acclaimed films like Parasite — despite being sophisticated in their aesthetic taste and intended audience, and highly self-aware about a capitalist or even neo-colonial class dynamic — find no respect for the poor. What is needed in art is not an insulting aesthetic romanticization of exploitation, but a respect for the strength, grace, and character that comes from honest struggle. This is completely absent from all of the lauded and addictive cultural exports we consume; Parasite skewers both the rich and the poor, depicting them as two ugly sides of what is ultimately the same coin, hopelessly warped by capitalism.

This problem with the K-Wave is not just that it reflects a certain set of capitalist values coming out of a history of imperialism and military occupation, but that it distorts this history in such a way to make it seem natural, authentic, or even something to be proud of as defining Korea and its people. But culture shouldn’t merely gather people together or form a basis for identity; it must provide a basis of values and a vision to continually shape and renew society.

The Folk Tradition: Grounded in Beauty and Truth from the People

Put simply, modern capitalist culture lacks the humanity and concrete grounding that would come from true closeness to the people. Unlike the K-Wave, folk culture and tradition has had a clarity about where life comes from: the peasants and the masses. This tradition understands where the moral lines must be drawn to respect this foundation of society, and accordingly, the values by which we ought to live if we are to have love or respect for the people and our history.

During the first half of the 20th century, despite the growing hegemony and censorship of Japanese imperialism, many artists continued to dig into the long tradition of Korean folk culture and history. They innovated on the original themes and motifs of the peasantry as an expression of the lost Korean land and its people, struggling through growing exploitation and poverty. Even in the South, the most enduring and beloved poems of the most popular poets (such as Kim Sowol’s “Azaleas,” or “Your Silence” by Han Yong Un) engaged with traditional forms and imagery which represented the classic and civilizational lifeworlds of the Korean people.

Poet Baek Seok (1912-1996) was one such poet, utilizing local dialects and centering traditional art and foods in his poetry, which consistently rooted itself in a kind of yearning for home, for closeness, and for the people. In his poem “A Poem of Pumpkin Flower Lanterns,” he wrote,

The heavens

Have more love for such a poet who stays close and among us

Even if such a poet is not known by the world, it is all right

Baek Seok’s humility — the humility he felt that a poet ought to have — is constantly reflected in his other poems. In “Mountain Lodge,” he wrote,

As I rest my head

On the rolling wooden pillows in the corner

I ponder the people visiting this mountain village whose sweat had stained those blocks black

I try to imagine their faces and feelings and life’s work.

Despite the poverty and lack of adornment of the people and environments he encountered on his travels, and rather than feeling disgust, guilt, or a desire to create distance, Baek Seok’s poetry expresses a deeply sincere respect and admiration for the people. In “Noodle Soup,” describing a family eating noodles at night, he asks,

This tranquil village, this village of dignified inhabitants, this deeply considerate and

close-knit place, what is it?

This unquestionably elegant yet simple thing, what is this?

Baek’s poetry is beautiful not because of his ornamental aesthetics, but because of the precise opposite: aiming honestly to get closer to the natural, humble, everyday reality of people reveals — and defines — beauty in its most pure and straightforward essence.

Like many others in the colonial period, Baek went abroad to study in Japan. Many of these students became politicized in their time abroad, growing conscious of the far-reaching and systemic cruelty of imperialist exploitation shared across countries. Political activity for self-determination and liberation lent a new dimension to their previous intellectual or artistic strivings for beauty and truth. These artists, intellectuals, and workers became educated — not in sophistication and the reproduction of worldly imperialist values, but genuinely educated, in the experiences and current of the progressive struggles taking place throughout the world.

Korean independence activists lived out their exile in China and Russia, operating the Provincial Government in Shanghai and continuing their activities abroad, and some students and activists similarly made their way to the United States to study and work. Despite the distance and large diversity in ideologies, a large number of these Koreans abroad learned from and unified around the broad principles of the people’s struggles for freedom and self-determination that were taking place at the time in the United States, China, and all across the world.

Coming Home to Our Great Inheritance: Unity with the Cultural Values of Afro America

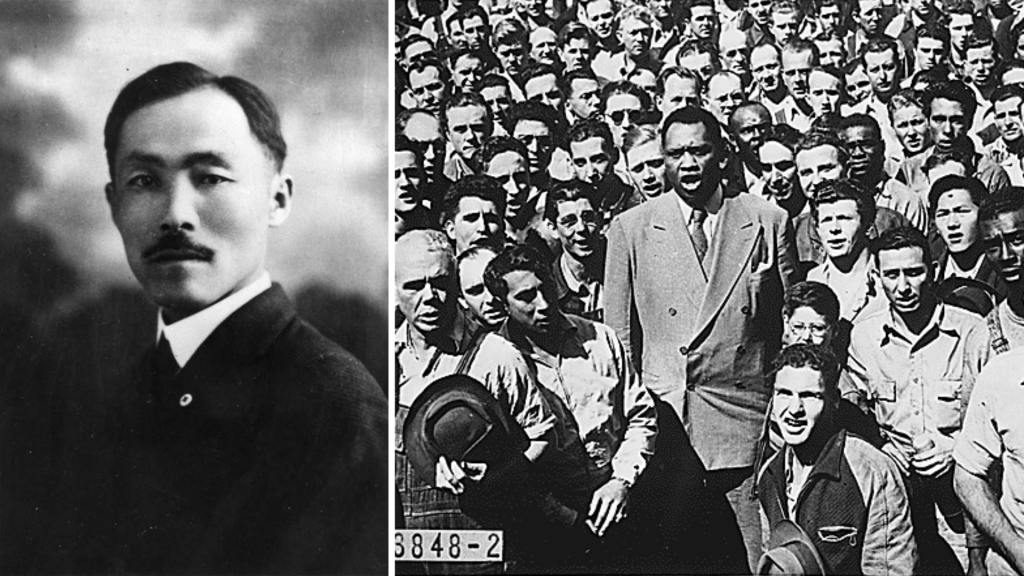

In America as well, we have many examples to look to. Ahn Chang Ho is widely recognized as a fighter for Korean independence and an early leader of Korean Americans in San Francisco. He established many organizations, including helping to found the Provisional Government of Korea in Shanghai in 1919, and advocated for the moral and spiritual renewal of the people’s character. Arrested and tortured by the Japanese many times, Ahn died in 1938, but has been considered by many as one of the key moral and political leaders of the Korean independence movement.

As Jang Jirak, a Korean communist and independence fighter, wrote of Ahn, “[Ahn] loved Negro songs especially and taught me several. We used to gather with him in Shanghai and sing “Old Black Joe,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” and “Massa’s in the Cold, Cold Ground.” His schools in Korea also taught these, and they became very popular there on moonlit lights. Koreans all love sad music dedicated to thoughts of bereavement, homesickness, and misery, so Negro melodies have a great appeal. I also loved these old songs.”

Paul Robeson, one of the greatest Americans and a true people’s artist, writes about the history and the significance of these Negro songs:

“…this enslaved people, oppressed by the double yoke of cruel exploitation and racial discrimination, gave birth to splendid, inspired, life-affirming songs. These songs reflected a spiritual force, a people’s faith in itself and a faith in its great calling; they reflected the wrath and protest against the enslavers and the aspiration to freedom and happiness. These songs are striking in the noble beauty of their melodies, in the expressiveness and resourcefulness of their intonations, in the startling variety of their rhythms, in the sonority of their harmonies, and in the unusual distinctiveness and poetical nature of their forms.”

Robeson never stopped singing the songs of the people, standing up in his global stature for truth and peace despite the anticommunist attacks made on him in the McCarthy era. His loyalty was broad, not narrow, as his love was for the working people all around the world for whom he performed.

The beauty and meaning of these Negro folk songs struck the Koreans who found themselves far from home in the United States, reminding them of their universal identification with oppressed peoples fighting for freedom. Han Se-Gwang (pen name Heuk Gu; 1909-1979) was a poet and writer who followed his exiled father Han Seung-Gon to the United States in 1929. Han’s father was a pastor and active participant in Heungsadan with Ahn Chang Ho, and Han studied literature and journalism in Chicago and Philadelphia from 1929-1934. In his time in the U.S., Han was deeply moved by the Negro laborers, their deep inner lives, and culture; he wrote that he “couldn’t leave the cotton fields when he heard southern Negroes singing a sorrowful song while picking cotton balls,” and that “the scenes of blacks who were working in the tobacco and cotton fields while singing homesick songs make me lost in contemplation whenever the autumn comes.”

In Han’s 1931 poem “In the Night Train,” the speaker identifies themselves in turn with freed Negroes, Polish women, and Irish maidens on the train from Halstead Street, while his short stories “An Elegy of Dusk” and “Letters from a Dead Comrade” condemn the societal treatment of Negroes, while highlighting the beauty and significance of their work songs. Han translated poems from Alain Locke’s The New Negro in his 1932 essay “A Study on American Negro Poets” for the monthly magazine Tonggwang, writing that Hughes portrays “the Negroes’ song of pent-up rage [which] overflows with brotherly love” in “Our Land.” The immense popularity of these poems is reflected by their translation in the Chosun Ilbo, a leading daily newspaper of the time. Han would also write poems in honor of Ahn Chang Ho, work on behalf of the independence movement, and write pieces such as his 1948 essay “The Status of Negro Literature” and his most famous 1955 work “Barley,” for which he is remembered as a writer interested in the exposition of human dignity and toil.

While folk songs represent the particular character of a people with distinct styles or specific motifs, they transcend the purely ethnic to join in the universal. In “The Related Sounds of Music,” Robeson wrote,

“Our music — the black music of African and American derivation — belonged to a great inheritance, to the great folk music of the world. These songs, ballads and poetic church hymns are… similar to the unknown singers of the Russian folktales, the bards of the Icelandic and Finnish sagas, singers of the American Indians… the Chinese poet singers… Systematic study and research seeking the origin of the folk music of different peoples in many parts of the world showed… that a world reservoir, a universal source of basic folk themes exists, from which the entire folk music is derived and to which they have a direct or an indirect tie. My interest in the universality of mankind — in the sense of a basic tie which all people have to each other — led to the idea of a universal source of folk music.”

Our inheritance is this culture born from the masses of people and their honest toil and striving: a tradition of hundreds and thousands of years of love, struggle, and sacrifice, spanning many continents and generations of peoples’ song, poetry, music, and art. People like Paul Robeson, Baek Seok, Han Se-Gwang, and Ahn Chang Ho were able to recognize this world inheritance, linking the history of their people and their times to where they were in their present. Unlike narrow and unprincipled South Korean nationalism, the values and character of folk culture espoused an absolute love for the people which required identification with all the oppressed and poor of the world, providing a basis for principled unity in the struggle against poverty, exploitation, and the violent injustices of imperialism.

A Culture for Peace, Unconditionally and Universally

After the end of Japanese military occupation, the U.S. seamlessly took over the Japanese system of governance, merely replacing Japanese colonialism with American neocolonialism, not even needing to replace many of the collaborators in high positions of power who simply changed loyalties again. The United States fostered an incredible anti-communism in the South. Dosan Park, named after Ahn Chang Ho, is many times smaller than the 630 acres of central Seoul that were dedicated to the American military after the Japanese occupation to freely control until as recently as 2018. Baek Seok, surely one of the greatest modern Korean poets, was entirely censored in the South until 1987 solely because of his labeling as a ‘North Korean’ poet.

The South Korean and Western media routinely paint North Korea as the ‘evil’ Korea, while South Korea is the ‘better’ of the two, because it sent men to kill in Vietnam and Afghanistan and Iraq at the behest of the United States, and because it has K-Pop, plastic surgery, and intense academic competition. The media paints the division of the peninsula as inevitable and perpetual. However, the division of the peninsula has been around for no longer than the Korean war generation, while elders live on both sides of the DMZ and still remember the war that tore families apart. In the face of two thousand years of history, how can war be ‘forever’ and peace an impossibility to even hope for?

The poets and independence activists of the colonial and anti-colonial era never ceased to feel love and responsibility for the people throughout their participation in the necessary moral struggle. We, of the diaspora today, have a lot to learn from their lives and the history that shaped their times. If we looked sincerely to this legacy we have to inherit, we would understand that the fight for our homeland is not over, and that in the history and folk traditions of the people, we could find unity, hope, and a shared path to walk towards the future to peace.

Further Reading:

Paul Robeson, “Don’t Ape the Whites,” 1935.

Paul Robeson, “Primitives,” 1936.

Paul Robeson, “Songs of My People,” 1949.

Nym Wales and Kim San, Song of Ariran.

Stephen Gowans, Patriots, Traitors and Empires: The Story of Korea’s Struggle for Freedom

Cho Myung Hui, “Naktong River,” 1927.

Baek Seok: Poems of the North.

한흑구 문학선집 (Han Heuk Gu Literary Selection), 2009.

Leave a comment