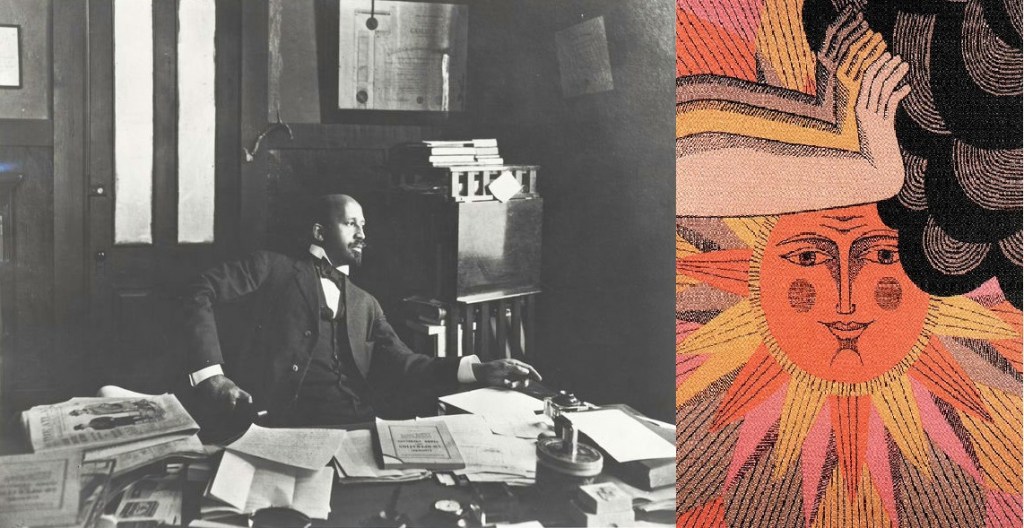

We are publishing today an excerpt taken from Russia and America, a work by W.E.B. Du Bois written in 1950 which provided a rare, truthful illustration of the Soviet Union’s revolutionary experiment towards socialism, and which subsequently went unpublished due to McCarthyism. Du Bois details and analyzes his trips to Russia, Asia, and Europe in which he not only observes the construction of the world’s very first workers state, but witnesses the wealth of potential those all over the world have to transform the very basis for civilization. He gives us a foundation for understanding places like Germany, Japan, and China in the context of a newly formed Soviet Union, and what this Russian experiment could mean for the darker world and the black proletariat in America. In the following passage, faced with a collapsing West entering World War II, Du Bois writes, “there is hope, vast hope” and further projects a vision for the unity of Pan-Asia that synthesizes a revolutionary democracy and communistic organization best seen in Russia with the traditions and ideals of great Asian civilizations. In a moment when the masses of the world are experiencing a compounding economic depression and Asia rises, we return to this writing like these in an effort to explore the potential of this historical moment.

The full text of Russia and America can be found here: https://credo.library.umass.edu/cgi-bin/pdf.cgi?id=scua:mums312-b221-i082

What next? Next could come a change in object on the part of Japan, and a change would mean that Japan and China together as equals would try to industrialize the East and produce goods which the East itself needs, as well as goods needed by the rest of the world. And these goods which the masses of China and Japan need, would by the pressure of the communistic trends in China be distributed upon a new basis, not according to the ideals of the West which Japan is now following so strictly; but according to a new ideal much nearer that of Russia and strangely enough corresponding also in part with that integration of Japanese family industry, which makes the nation one industrial whole instead of the class-divided industrial systems which one expects.

It must, of course, be Marxian in its abolition of industrial profit, toward which family and state communism in Asia already tends, but which has been frustrated by European influence. It must be Marxian in its division of income according to need; but it may be distinctly Asiatic in its use of the vertical clan division and family tie, instead of reaction toward a new bourgeoisie along horizontal class layers which must be the temptation of Europe.

It would take a new way of thinking on Asiatic lines to work this out; but there would be a chance that out of India, out of Buddhism and Shintoism, out of the age-old virtues of Japan and China itself, to provide for this different kind of Communism, a thing which so far all attempts at a socialistic state in Europe have failed to produce; that is a communism with its Asiatic stress on character, on goodness, on spirit, through family loyalty and affection might ward of Thermidor; might stop the tendency of Western socialistic state to freeze into bureaucracy. It might through the philosophy of Gandhi and Tagore, of Japan and China, really create a vast democracy into which the ruling dictatorship of the proletariat would fuse and deliquesce; and thus instead of socialism even becoming a stark negation of the freedom of thought and a tyranny of action and propaganda of science and art, it would expand to a great democracy of spirit.

There is hope here, vast hope. But the horror of it all is to see the fear of Soviet Russia and the blandishments of Germany and, perhaps, even of Italy, seducing Japan away from China and Asia and seeking to create a Fascist bloc which the finer world eventually must kill, or itself perish.

To me, the tragedy of this epoch was that Japan learned Western ways too soon and too well, and turned from Asia to Europe. She had a fine culture, an exquisite art, and an industrial technique unsurpassed in workmanship and adaptability. The Japanese clan was an effective social organ and her art expression was unsurpassed. She might have led Asia and the world into a new era. But her headstrong leaders chose to apply Western imperialism to her domination of the East, and Western profit-making replaced Eastern idealism. If she had succeeded, it might have happened that she would have spread her culture and achieved a co-prosperity sphere with freedom of soul. Perhaps.

In the dying days of 1936, while great Fujiyama still veiled its silver face, I went down to Yokohama and set foot upon the sea. I sailed east into the sunset again to discover America, in my own thought and through the thinking and doing of other folk. Ten days I journeyed until I came, at Christmas, to an unbelievable land of raining sunshine and everlasting flowers, called Hawaii.

New Years, 1937, I stood in California of fact and fable, with the city of St. Francis of poverty and the birds before me and lifted up mine eyes to the hills beyond the Golden Gate, which form the rock-bound spiral column of America. Lifted them and let drop two small years; to little years; suddenly I saw the whole world aflame.

Leave a comment