The art and music of a people can tell you much about their moral and spiritual state. In fact, one of the things that defines the state of a civilization at any moment in history is the art and literature that it produces. We are living in times of anxiety, confusion and pessimism, and the movie Sorry to Bother You is an exemplary illustration of this fact.

The movie was released in 2018 and received much critical acclaim. The New York Times said of rapper turned movie director Boots Riley, “He is after big game, though — race and class, labor and capital, art and technology — and his aim, while eccentric, is very often true.” Even the slightly critical reviews were positive — the Atlantic said that “the misses are as interesting as the hits.” Its review in the Jacobin, a left journal, started with the sentence, “I’ve been rooting so long for somebody to make an anticapitalist black comedy that I’m shocked somebody finally did”. At first sight, this movie seems to be a strong critique of racial capitalism and the alienation arising from it. It depicts workers as cogs in the enormous capitalistic machine, and recognizes the importance of the war industry to capitalism. The movie also succeeds in its depiction of the moral bankruptcy of the rich.

Perhaps the most jarring fact of the movie, however, is the complete lack of beauty in it. The narrative paints a terrible picture of selfishness and moral degradation; a society which poses a choice before young people — sell out your principles and friends for luxury or live forever in poverty and humiliation. The main characters that are defined in the film are either clamouring over each other to get to the top, or too cowardly to lead a principled life of sacrifice. While the basic choice posed might be true in our times, the characters that are used to pose it are too horrifying, and it makes the movie singularly unbelievable as a portrait of human beings. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote of Richard Wright’s book Black Boy,

“One rises from the reading of such a book with mixed thought. Richard Wright uses vigorous and straightforward english; often there is real beauty in his words, even when they are mingled with sadism… Yet at the result one if baffled. Evidently if this is an historical record, bad as the world is, such concentrated meanness, filth and despair never completely filled it or any particular part of it. But if the book is meant to be a creative picture and a warning, even then, it misses its possible success because it is in itself unbelievable or impossible; it is the total picture that is false.”

This is how the movie leaves one feeling. It is true that poverty and the system of racial capitalism distorts people, and makes them compromise on their principles, but is it true that this is always the case? How is it possible that not a single character in the movie shows qualities of sacrifice, loyalty, kindness or altruism?

The movie presents us with Cassius (“Cash”) Green, a young black man struggling with poverty and disillusioned with the world he finds himself in. He is desperate to escape this fate, and as the movie unfolds, we see him choose money, fame and luxury over his friends and a potentially powerful union struggle. He makes this choice over and over again, although we see him feel the tension in this choice. In the end, he discovers that the evil corporation Worryfree is genetically modifying humans to create equisapiens, horse-men creatures, to create stronger, more efficient workers. Only when he is faced with this colossal moral question, this situation that threatens to change the definition of humanity itself, does he make a moral decision to make people aware of the corporation’s deeds, and side with those he loves. One should mention that even this decision is suspect, since he makes it after he thinks that he himself might also have ingested a chemical that may turn him into one of these creatures.

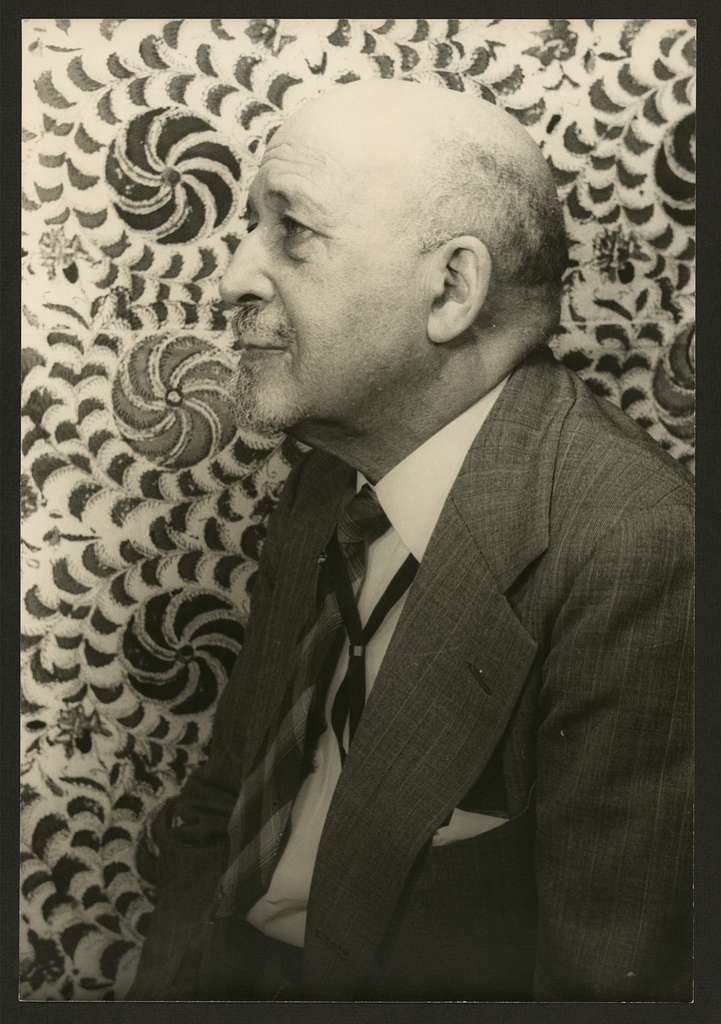

Some may argue that the Asian organizer in this film is an example of altruism. This character is present all around us in today’s society; he is almost a stereotype. Both him and the character of Cassius’ girlfriend, Detroit, are drawn from ‘woke’ culture, a culture of self righteousness, divorced from the history of struggle. They both see the struggle of working people in an economic system that relies on keeping them oppressed, but fail to recognize the principle agent that can carry out revolutionary change — the black proletariat. Race is not just a byproduct of a capitalist system, but as W.E.B. Du Bois said, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line”. Indeed, Boots Riley falls further into the trap of the white left — thinking that people are shaped conclusively by their material conditions. He misses the truth of life — that working people are beautiful. Beautiful in the sense of struggle and sacrifice, of tragedy. They possess the kind of beauty that one sees in the Negro Spirituals, the murals of Diego Rivera, the paintings of Charles White, or the writing of James Baldwin and Maxim Gorky. Yes, there is the grittiness, horror and moral debasement of poverty, but out of this is wrought a magnificent humanity.

As Du Bois says further in his review of Black Boy,

“At any rate the reader must regard it as creative writing rather than simply a record of life. Consequently he must ask: how far has the artist achieved the impression that he set out to make? The result to my mind is not successful. It is overdrawn. It is terrible, whether or not it is true. As an artist certainly the writer ought to have lightened his picture even if simply to make the shadows darker and more horrible. As it is, one reads and rereads this novel with the growing realization that there is not a single lovable person within its pages. Everyone is wrong: white people and black people, ministers and teachers, old people and young people.”

The story of Sorry to Bother You is pathos, rather than a tragedy. This is even more of a betrayal by Boots Riley as many of the characters he attempts to draw out are African Americans. As the history of the nation shows, Black America as a whole has never subscribed to the values and morality of White America. This is proved by the existence of movements such as the Nation of Islam and the Black Freedom and civil rights movement. Black people as a whole have been suspicious of the white system of governance, and been at the vanguard of change within this nation. The black characters in Sorry to Bother You make no philosophical reference to this history. It is as if they have no connection to the legacy of thought and action that came from figures such as Paul Robeson, James Baldwin, W.E.B. Du Bois or Martin Luther King Jr. These are nothing but white characters with black voice. There is no recognition of the fact that the Black community in America is shaped by their history of oppression and struggle, and often operate from different assumptions about white society than white Americans. The superficial allusions to black voice and images of Huey Newton appear as nothing but a gimmick. A deeper analysis of black life, and in particular Black community life in the form of the church and civil organizations, is missing. This is strikingly superficial in the depiction of a people for whom the church predated the family on American soil. Boots Riley does not represent accurately the ‘world within a world’ that is Black America, and instead reduces race to a cultural trope.

Du Bois outlines the responsibility of black artists in light of their history in his essay “Criteria of Negro Art”,

“We black folk may help for we have within us as a race new stirrings; stirrings of the beginning of a new appreciation of joy, of a new desire to create, of a new will to be; as though in this morning of group life we had awakened from some sleep that at once dimly mourns the past and dreams a splendid future; and there has come the conviction that the Youth that is here today, the Negro Youth, is a different kind of Youth, because in some new way it bears this mighty prophecy on its breast, with a new realization of itself, with new determination for all mankind.”

He goes on to say,

“Thus it is the bounden duty of black America to begin this great work of the creation of Beauty, of the preservation of Beauty, of the realization of Beauty, and we must use in this work all the methods that men have used before. And what have been the tools of the artist in times gone by? First of all, he has used the Truth — not for the sake of truth, not as a scientist seeking truth, but as one upon whom Truth eternally thrusts itself as the highest handmaid of imagination, as the one great vehicle of universal understanding. Again artists have used Goodness — goodness in all its aspects of justice, honor and right — not for sake of an ethical sanction but as the one true method of gaining sympathy and human interest.”

Ignoring the history of Black people in America also leads Boots Riley to present us with infantile and immature versions of activism. The first method for changing the world we can see in the film is the union organizer. While the union struggle may have been a powerful challenge to the forces of capital in the 1930s and 40s, they were compromised by the onslaught of McCarthyism in the 50s. Today, union organizing is a stable career path for young college graduates and is no more than a tool for the Democratic Party to exercise control over working people. Unions are a shadow of their former selves, and gone are the days when they could take principled stances against war and poverty. In an interview with Democracy Now, Boots Riley talks about the turn of the left away from class struggle and towards spectacle. While this is certainly true, the movie does not offer a way forward in carrying out the struggle in America. The second alternative he offers us is anarchist action, as is seen in the character of Cassius’ girlfriend, Detroit. She runs around Oakland painting graffiti with a group that reminds one of Antifa. This sort of infantile behaviour is nothing more than a cathartic release of anger and frustration, and it is more about the activists themselves than about the masses of working people. Why does Boots Riley not even consider the history of Black struggle in the United States? Where is the revolutionary tradition of a Malcolm X, a Henry Winston or a Martin Luther King?

The reason is that Boots Riley is engaging in a white debate. In this time especially, if one is familiar with the history of the color line and Western imperialism, they know that the question of the future is not simply one of capitalism or socialism — instead it is one of choosing either western civilization and the values that form its basis, or the rest of humanity. Although the war industry is mentioned as one of the primary clients of the power callers in the movie, Boots Riley clearly does not see the question of war and western imperialism as the central one of our times.

The movie presents us with the dystopia of physically disfigured human beings, and really the ugliness with which it depicts this makes one shudder with shock and horror. However, the movie misses the real dystopia of our times — the crushing of human potential under the weight of poverty. Is physical disfiguration really that much worse than the world we currently live in, where children remain hungry, unclothed and uneducated? This is a white vision of dystopia — one that does not recognize the tragedy and horror of our times, and uses sheer ugliness to attempt to shock the white world out of its pathos. The ending of the movie is a bizarre dystopic vision — a revolt against the capitalist class by equisapiens. This mere reaction to oppression is meant to represent revolutionary hope, but it fails. Further, great artists know that you do not need such fantasy to draw out drama, the stories of human life all around us are full of it — tragedy, love, jealousy, sacrifice, joy. As Du Bois says,

“We are remembering that the romance of the world did not die and lie forgotten in the Middle Age [sic]; that if you want romance to deal with you must have it here and now and in your own hands. I once knew a man and woman. They had two children, a daughter who was white and a daughter who was brown; the daughter who was white married a white man; and when her wedding was preparing the daughter who was brown prepared to go and celebrate. But the mother said, “No!” and the brown daughter went into her room and turned on the gas and died. Do you want Greek tragedy swifter than that?”

One may ask, why should one not make art absurd to shock its viewers? Is it entirely fair to hold the artist to the standard of reality, and demand that they show beauty? To this Du Bois answers in the “Criteria of Negro Art”,

“Such is Beauty. Its variety is infinite, its possibility is endless. In normal life all may have it and have it yet again. The world is full of it; and yet today the mass of human beings are choked away from it, and their lives distorted and made ugly. This is not only wrong, it is silly. Who shall right this well-nigh universal failing? Who shall let this world be beautiful? Who shall restore to men the glory of sunsets and the peace of quiet sleep?

I am one who tells the truth and exposes evil and seeks with Beauty and for Beauty to set the world right. That somehow, somewhere eternal and perfect Beauty sits above Truth and Right I can conceive, but here and now and in the world in which I work they are for me unseparated and inseparable.”

As Du Bois insisted, all art is propaganda. What is the propaganda of this movie? If the aim is to merely depict the pessimism and moral bankruptcy of our times, Boots Riley succeeds in a somewhat limited way. It is overdrawn and thus untrue. However, if the aim is to inspire hope and a way forward for people in this time of crisis, the movie fails miserably. Further, the reader may ask the question, what should the aim of art be in this time of crisis and confusion? The artist who holds himself to the people would answer as James Baldwin once did, “The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.”

Leave a comment